Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for more than 99 percent of total businesses in emerging world regions (Eniola & Entebang, 2014). Therefore, these institutions are crucial to the economic health of a nation. It is extremely concerning that many long-standing small firms and industries fail (Eniola, 2018). Researchers opined that SMEs frequently employ marketing management approaches like brand equity, quality, personality, and customer satisfaction to emphasise their competitive advantages (Auemsuvarn, 2019; Fourie, 2015; Selase Asamoah, 2014). Although brand personality has been shown to increase both a company’s competitive advantage and customer satisfaction, little attention has been paid to how SMEs might put it to use.

The service industry has become a very important part of all economies around the world as markets have become more focused on services. The global service sector has, however, seen an increase in competitiveness, making it increasingly important for successful businesses to have a thorough grasp of their clients’ behaviour (Hosseini & Saravi-Moghadam, 2017). Despite being exploratory, the development of the brand personality scale brings together a significant study that has proven helpful in corporate planning and marketing applications. Ouwersloot and Tudorica (2001) observed that firms must be able to use brand personality as a strategic instrument to attain consumer satisfaction regarding brand personality concerns. Brand personality, as proposed by Yi and La (2002), has both direct and indirect effects on brand loyalty through the satisfaction consumers feel when interacting with the brand itself and with the brand’s representatives. Additionally, Roustasekehravani et al. (2014) showed that brand personality significantly affects satisfaction. This means that increased levels of customer satisfaction are expected when there is a greater degree of congruence between the brand’s personality and that of the target audience.

A brand’s “personality” is an attribute that helps consumers connect with it on a more emotional level (Auemsuvarn, 2019; Geuens et al., 2009). Consumers are more likely to like a brand if they see themselves reflected in the product or service (Auemsuvarn, 2019; Khan & Ahmed, 2018; Rutter et al., 2018). Customers subsequently grow and forge a better connection with brands. Businesses can keep a competitive edge with a well-developed brand personality (Rutter et al., 2018). This is because a well-developed brand personality makes a product stand out from the crowd.

This research is significant for a variety of reasons. First, large companies and well-known brands around the world have strong brand personalities, while their smaller competitors do not. This is due, in part, to the fact that investing in the personality of a brand demands a commitment over a prolonged period (Agostini et al., 2015; Auemsuvarn, 2019; Odoom et al., 2017). For this reason, product categories where SMEs play little role in promoting their brands do not make extensive use of brand personalities. Second, contrary to the widespread belief that every organisation needs to establish strong brands as an integral aspect of their business plan, the significance of brand personality in SMEs is distinct (Kay, 2006). In contrast, many small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) managers appear to believe that effective branding is beyond their reach and their actions reflect this belief. SMEs may not put much effort into brand management because they do not know much about it and are not sure if it helps their business’s quality and performance (Hirvonen & Laukkanen, 2014; Muhonen et al., 2017). Even though it has been argued that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) should incorporate brand personalities into their strategic planning, it is unclear whether or not SMEs should or may employ the same branding practices as large corporations (Muhonen et al., 2017).

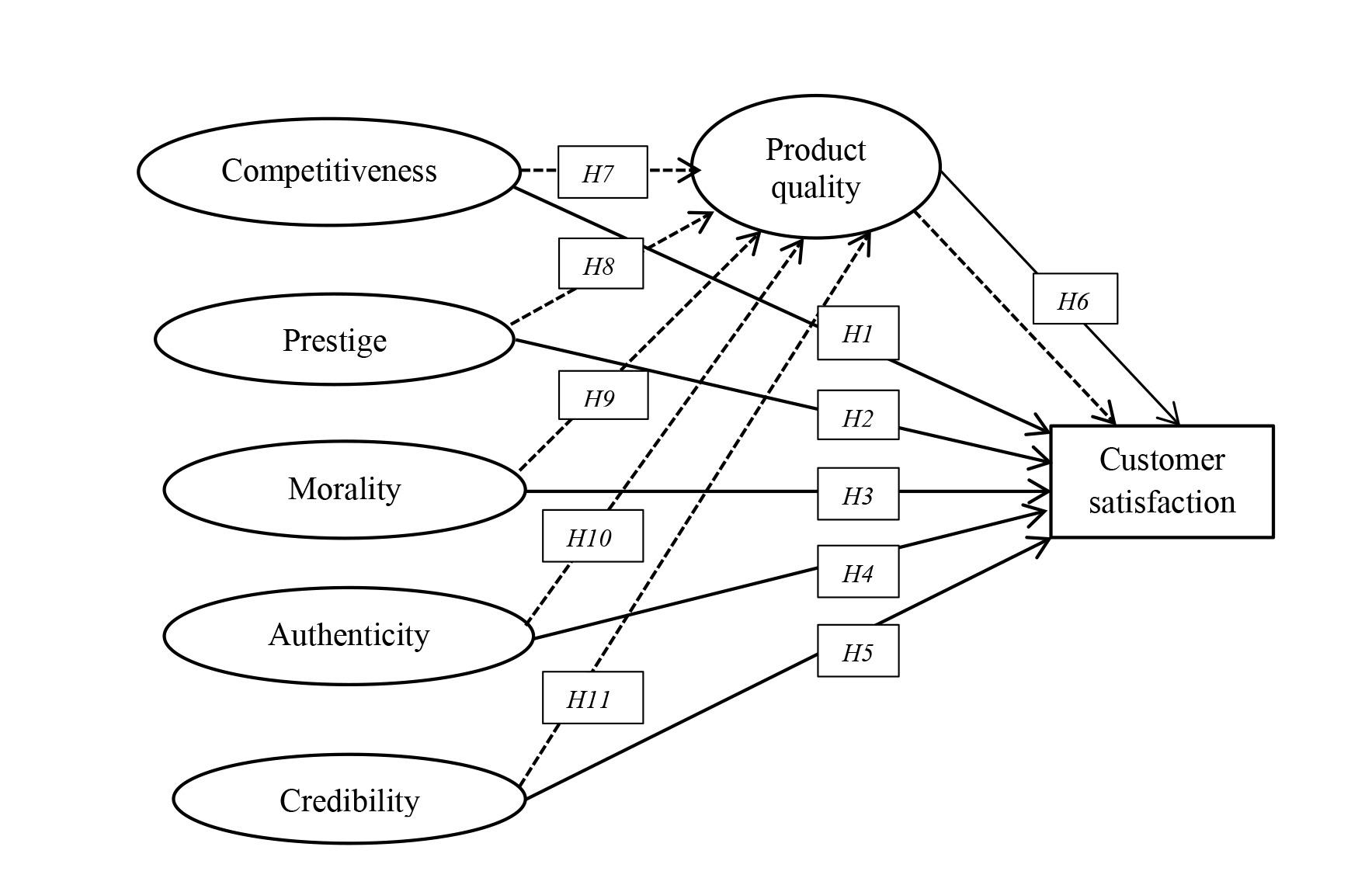

According to Mirabi et al. (2016), most previous empirical studies that looked at the link between brand personality and satisfaction did not consider the possibility of variables that could act as mediators or moderators. The most essential benefit of brand personality is that it allows businesses to highlight the unique qualities of their products and communicate those qualities directly to consumers (Strizhakova et al., 2011). Every day, customers decide between buying branded products and generic ones from the vast selection available to them (Strizhakova et al., 2011). Therefore, consumer satisfaction with a product’s personality depends on how they utilise brands to determine product quality (Strizhakova et al., 2011). Despite the significance of brand personality, only a few empirical studies on SMEs have been conducted (Balakrishnan et al., 2009). To this end, this study will explain and put to the test a model that looks at how SMEs’ brand personalities affect customer satisfaction. Similarly, the research intends to examine how quality influences the relationship between SME brand personality and customer satisfaction. The study will concentrate on explaining how different aspects of quality affect the perception of SME brand personality and thus influence consumer satisfaction levels. The study will investigate how product quality, service quality, and brand familiarity influence consumer perceptions and satisfaction in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Literature review

Business practitioners have been using the concept of brand personality in their marketing and advertising campaigns even before an acceptable concept was coined (Azoulay & Kapferer, 2003). The idea that brands are endowed with personality traits was first suggested by Gardener and Levy in 1955. Although the concept of brand personality is less common in SMEs, it is widely used across many domains. Though there are many definitions of brand personality, the most striking one is that of Aaker (1997), who conceptualised it as “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand” (Aaker, 1997); thus, there is a tendency to ascribe human personality traits to brands. Subsequently, researchers have consistently reasoned that brands, much like people, take on personality characteristics (Freling & Forbes, 2005; Keller, 2003). These human-like characteristics permit marketers to assign a distinct personality to brands (Thomas & Sekar, 2008).

In addition, in an attempt to conceptualise brand personality, a scale was developed to measure it. Aaker (1997) developed a framework that was rooted in the research of psychologists on human personality. The framework that was developed has dominated brand personality studies. In her study, Aaker (1997) identified five dimensions of brand personality: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Over the years, this model has dominated brand personality research and has been applied in different contexts and to different brands. However, upon its extensive use, it has been criticised that Aaker’s brand personality model is strongly related to culture, whereby the personalities of brands depend on the socio-cultural context; thus, studies have unearthed new and separate cultural dimensions of brand personalities in different societies. The results of studies such as Chu and Sung (2011); and Anandkumar and George (2011) provide adequate evidence that Aaker’s model is not generalisable across cultures. In addition, Kumar (2018) reviewed extant literature and indicated that some of the categories of criticism that abound in the literature include definition-related, dimension-related, methodology-related, and concept-related.

Despite all the criticism of Aaker’s brand personality, it has been employed widely in research and on brands across many socio-cultural contexts (Kumar, 2018). As such, it has been observed that the model is not always best suited to all contexts, products, and services. Because of the need to find the best-fitting models for different brands in different cultural setups and the flaws associated with Aaker’s (1997) brand personality model, several scholars have attempted to develop new brand personality measures, based on this scale (Kakitek, 2018). The first response to the criticism of Aaker’s 1997 brand personality was the work of Bosnjak, Bochmann, and Hufschmidt (2007), who suggested a new brand personality measure that is particular to the German context and consists of the following dimensions: drive, conscientiousness, emotion, and superficiality. Geuens, Weijters, and De Wulf (2009) propounded a new measure of brand personality consisting of five dimensions: activity, responsibility, aggressiveness, simplicity, and emotionality.

Tsiotsou’s brand personality

Tsiotsou (2012) undertook a study of brand personality in Greece and developed a brand personality scale to measure the personality of professional sports teams. The scale comprises five dimensions, namely: competitiveness, prestige, morality, authenticity, and credibility. and has 19 items as shown in Figure 1.

According to Tsiotsou (2012), competitiveness was conceptualised as the ability of a sports entity to win games and attain its goals. Prestige entails how superior the team is, as observed by its achievements. Morality refers to the sports team’s code of conduct. Authenticity relates to the exclusivity of the team, and credibility entails the ability of the team to inspire trust and confidence.

There is a proliferation of brand personality measures that are used to measure various products, services, and ideas. Among numerous brand personality scales, are those that measure the brand personality of social media (Garanti & Kissi, 2019; Mutsikiwa & Maree, 2019), universities (Ahmed & Ali, 2020), banks (Jan & Shafiq, 2021), world heritage sites (Hassan, Zerva, & Anlet, 2021), destinations (Wang et al., 2022), physicians (Shafiee et al., 2022), and sports (Tsiotsou, 2012). Despite the existence of many scales, there is yet to be an existing brand personality scale that measures the brand personality of SMEs, and as such, researchers have decided to extend Tsiotsou’s (2012) scale to this domain area that lacks a best-fitting scale to substantiate its applicability and examine how the various dimensions of the scale will affect customer satisfaction directly and indirectly.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

The theory of anthropomorphism serves as the theoretical foundation for this study. Anthropomorphism is described as the tendency to attribute human traits, feelings and behaviour to non-human entities to make sure that the actions of other individuals are understandable and explainable (Duffy, 2003). Anthropomorphising the non-human entity is evident in extant literature – for example, marketing practitioners have anthropomorphised brands to encourage consumers to perceive human traits in non-human agents (Aggarwal & McGill, 2011). Thus over the years, the theory has been employed to explain the motivation behind humanising non-living things. Its initial application was mostly noted in the religion domain (Fisher, 1991), where the personality of God is regarded as that of a person with mystical powers. Thereafter, it has been applied to many disciplines such as marketing in promotional campaigns (Puzakova et al., 2009), social sciences (Kim & McGill, 2011), engineering and product designs (Guido & Peluso, 2015), and social media (Mutsikiwa, 2018) among others. The ascribing of human attributes to these domains has been considerably successful, as such this study would like to apply the theory to the SMEs context and examine the human traits that customers prescribe to this domain area.

Hypotheses development

Competitiveness and customer satisfaction

According to Fleejterski (1984), competitiveness is conceptualised as “the capacity of the sector, industry or branch to design and sell its goods at prices, quality and other features that are more attractive than the parallel characteristics of the goods offered by the competitors”. SMES must attend to customers’ changing needs for them to deliver superior quality effectively and efficiently which enhances customer value and customer satisfaction. In this study, it is anticipated that if SMEs charge prices that are well below those charged by their competitors for similar products, this may ultimately lead to customer satisfaction. Based on the above, it is therefore hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 1: Competitiveness positively customer satisfaction

Prestige and customer satisfaction

Prestige relates to a comparatively high status of product/service positioning connected to the brand (Steenkamp et al., 2003). A brand is regarded as prestigious when it is endowed with unique attributes such as product quality and performance. Consumers perceive prestige based on the outstanding success of the brand. Literature also states that brand prestige is developed through constant interactions with customers (Vigneron & Johnson, 1999). It is broadly accepted that a prestigious brand is a significant way to reflect their self-esteem, and as such satisfies consumers (Steenkamp et al., 2003). With the increasing growth and development of SMEs in developing economies – such as Zimbabwe, it is important to comprehend how the prestige of SMEs brands can influence consumers’ satisfaction. Because of this, we assume that if SMEs provide prestigious products and services to their customers then they are likely to satisfy them. Therefore it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 2: Prestige positively affects customer satisfaction

Morality and customer satisfaction

Perceived organisational morality denotes the extent to which organisations are perceived by their various stakeholders as upholding universal moral values such as honesty, sincerity, and trustworthiness (Haidt & Graham, 2007). In a previous study, Leach et al. (2007) examined the role of morality as an organisational asset. In another study by Ellemers (2017), the research findings have shown that organisational employees are generally motivated to behave morally and suggested that moral image plays a significant role in motivating and keeping employees. It is therefore assumed if employees that are associated with SMEs can uphold moral values that are appealing to the customers they may enhance customer satisfaction. Therefore it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 3: Morality positively affects customer satisfaction

Authenticity and customer satisfaction

Authenticity originates from the Greek word ‘authentes’ – which denotes originator or creator. Something that is regarded as authentic is considered genuine and real. Researchers have examined authenticity in different contexts. According to Liu et al. (2018), authenticity plays an important role in determining customer satisfaction. Lu (2012) also notes that authenticity has been studied in the context of restaurants to determine its effect on restaurant satisfaction and return intentions and the results of the study have shown that the perceived authenticity of restaurants influences satisfaction (Jang et al., 2012). Despite the consensus that authenticity is a key antecedent to customer satisfaction, this has not been tested in the context of SMEs. We assume that the satisfaction of customers depends on the performance of the SMEs products and services – thus if they meet the expectations of the customers then satisfaction is enhanced. As such we consider that the perceived authenticity of SMEs products and services will have a significant effect on customers’ satisfaction. Therefore it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 4: Authenticity positively affects customer satisfaction

Credibility and customer satisfaction

According to Parasuraman et al. (1985:47), credibility denotes “trustworthiness, believability and honesty”. Credibility in SMEs comes from the source. Thus, source credibility in this study would be regarded as the perception that consumers have about the products and services offered by SMEs – the extent to which the customer believes that the product or service can deliver what has been promised. Thus if SMEs are considered as credible sources, their products will lead to consumers’ satisfaction. Extant literature acknowledges that source credibility is rooted in three dimensions namely: attractiveness, expertise and trustworthiness (Pornpitakpan, 2004) and competence (Sweeney & Swait, 2008). Thus if SMEs are considered as credible sources, their products will lead to consumers’ satisfaction. Therefore it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 5: Credibility positively affects customer satisfaction

Product quality and customer satisfaction

Zeithmal (1988) defines perceived quality as the consumer’s perception of the superiority of products or services in their ability to meet their intended purpose, compared to alternatives. Amanah (2010) regards product quality as the ability of a product to perform the expected functions as per customers’ expectations. Thus a product has to be compatible with the needs of consumers. This entails that the product should perfectly meet the customers’ preferences, such as high quality, reliability, ease of use and durability among others. Scholars such as Jahanshahi et al. (2011) and Etemad-Sajadi and Rizzuto (2013) have conducted empirical studies and results have substantiated that product quality has a positive influence on satisfaction. Thus, in the context of this study, we assume that the quality of SMEs products contributes to the satisfaction of customers. Based on the above research findings we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6: Product quality positively affects customer satisfaction

The mediating role of product quality

Over and above the direct effects hypothesized earlier, we also set out to examine the mediation (indirect) effects of product quality. First, in the context SMEs in developing countries, we anticipate indirect effects of all the variables (competitiveness, prestige, morality, authenticity and credibility) on customer satisfaction that is mediated by product quality. Prior studies have examined the mediating effect of product quality over many variables like customer value and customer reputation and the results have revealed that it had a significant mediating effect (Chang & Zhu, 2011). Therefore it is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 7: Product quality mediates the relationship between competitiveness and customer satisfaction.

Hypothesis 8: Product quality mediates the relationship between prestige and customer satisfaction.

Hypothesis 9: Product quality mediates the relationship between morality and customer satisfaction.

Hypothesis 10: Product quality mediates the relationship between authenticity and customer satisfaction.

Hypothesis 11: Product quality mediates the relationship between credibility and customer satisfaction.

Methodology

Population

The population of this study consisted of customers of SMEs with specific references to hardware brands. The data employed in this study was collected from SMEs customers between March and April 2023 during weekends because the research assistants used in this study were free at weekends. The research assistants were initially trained so that they could collect data, through a five-minute self-administered questionnaire. The training for data collection focused on providing research assistants with a thorough grasp of how to administer the questionnaire. The instructions included how to engage potential participants, clarify the study’s objectives, and offer assistance in filling out the questionnaire. The research assistants were trained to manage various situations during data collection, including handling uncooperative respondents and addressing any uncertainties about the questionnaire items. They were also informed about ethical issues, confidentiality rules, and data protection measures. The questionnaire had a trial run to assess the clarity, comprehensibility, and reliability of its items. The pre-test is used to detect any ambiguities or confusing elements in the questionnaire and make any required revisions before the official data gathering commences. It guarantees that the questionnaire accurately collects the required information and helps participants provide precise replies. The respondents were intercepted as they did their shopping within the SMEs.

Measures

Based on the research model and a comprehensive review of the literature, the proposed model was then operationalized using previously used and validated items. The study employed a self-administered and structured questionnaire consisting of two parts namely the demographic and variable sections. The demographics entailed gender, age, education and monthly income. All the items relating to the research constructs – competitiveness, prestige, morality, authenticity, and credibility were adapted from Tsiotsou’s sports brand personality model (Tsiotsou, 2012). Product quality was operationalised using 5 items adapted from Yoo and Donthu (2001) and customer satisfaction was adapted using 4 items from Dutta et al. (2017). To assess the measures of the study contained in the questionnaire, a 5-point Likert-type scale was employed with indicators that ranged between ‘1 = strongly disagree’ to ‘5 = strongly agree’. Competitiveness was tested using 6 items, prestige using 5 items, morality 3 using items, authenticity using 3 items and credibility using 2 items.

Sample and data collection

Convenient sampling was preferred as a sampling method for this study. It is a non-probability sampling technique that selects participants that are available around a given place – as such the researchers collected data from the participants who were met while they were doing shopping on SMEs. In a bid to determine the rightful participants a screening question was used to exclude candidates who did not qualify to participate in the study. The screening question entailed that of age – any customer who was less than 18 years old and who was purchasing the SMEs products for the first time was excluded from the survey. At the end of the survey, only 263 questionnaires were collected. Only 240 questionnaires were considered valid and were then used for data analyses.

Data analysis

Sample profile

Table 1 depicts the sample’s demographic characteristics. As is depicted in Table 1, the sample is skewed towards male participants (62.5%) and fewer female participants (37.5%). The participants are generally young and educated people with relatively low monthly incomes.

Descriptive statistics

The reliability of the measurement scales used to measure the research constructs was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha index. According to Nunally (1978), a scale is regarded as reliable when it has a value of at least .7. Given that, all the reliability index values surpassed the suggested values, the scales were deemed reliable. To assess the validity of the construct, both convergent and discriminant validity were examined. The researchers used the average variance extracted and composite reliability to examine the convergent validity and all the values exceeded .5 and .7 as suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981). Table 2 shows the reliability and convergent values.

Discriminant validity

The assessment of the discriminant validity of the model was done through the comparison of the average variance extracted and the squared inter-item correlations. As suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981), all the values of the average variance extracted were bigger than the squared inter-item correlations of the constructs and as shown in Table 3 and as such the model had discriminant validity.

Structural Model Analysis

Model fit test

The model fit test employed the fitting parameters shown in Table 4 that is, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Normed Fit Index (NFI), Squared Euclidian Distance (d-ULS) and Geodesic Distance (d-G). For the model to be regarded as fitting the SRMR value has to be below 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1998), the NFI has to be above 0.9 (Byrne, 1994), the Squared Euclidian Distance (d-ULS) and Geodesic Distance (d-G) have to be less than 0.95 (Hair Jr and Hult, 2016). The bootstrapped results indicated that the SRMR value was 0.057 (< 0.08), the NFI value was 0.934 (> 0.90), the d-ULS value was 0.813 (< 0.95) and d-G value was 0.798 (< 0.95). Consequently (see Table 4), the model is accepted as fitting to the data. As such the hypothesis testing was run accordingly.

Hypotheses testing

Direct effects

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) technique using Smart PLS-3 was used to test the hypotheses of the study, and the outcome is shown in Table 2. The researchers adopted the PLS algorithm coefficient values. A bootstrapping method was used to examine the significance of the path coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), and t-statistical values (t) with 5000 resamplings. As depicted in Table 2, competitiveness had a significant relationship with customer satisfaction as shown by (β = 0.263; SE = 0.052; t = 4.944; p <.05), thus supporting H1, prestige had a significant positive relationship with customer satisfaction as indicated by (β = 0.345; SE = 0.043; t = 5.312; p <.05 ), rendering support to H2, morality had a significant positive relationship with customer satisfaction (β = 0.405; SE = 0.032; t = 3.320; p <.05), thus supporting H3, authenticity had a significant positive relationship with customer satisfaction (β = 0.271; SE = 0.021; t = 8.132; p <.05), supporting H4, credibility had a significant positive relationship with customer satisfaction (β = 0.572; SE = 0.043; t = 9.653 p <.05; ), supporting H5 and product quality had a significant positive relationship with customer satisfaction (β = 0.306; SE = 0.053; t = 2.486; p <.05), rendering support to H6.

Mediation effects

The product coefficients approach was employed to estimate the mediating effects of product quality by the use of bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). Centred on the results from the PLS 3 output, depicted in Table 4, perceived product quality mediated the relationships between all the independent variables with customer satisfaction. Particularly, competitiveness indirectly impacted customer satisfaction through product quality (β = 0.542; SE = 0.027; t = 4.328; p <.05), thus supporting H7, prestige indirectly influences customer satisfaction through product quality (β = 0.198; SE = 0.054; t = 4.425; p <.05), thus supporting H8, morality indirectly influences customer satisfaction through product quality (β = 0.326; SE = 0.026; t = 5.640; p <.05), thus supporting H9, authenticity indirectly influences customer satisfaction through product quality (β = 0.256; SE = 0.048; t = 3.300; p <.05), thus supporting H10 and credibility indirectly influences customer satisfaction through product quality (β = 0.413; SE = 0.035; t = 4.334; p <.05), thus supporting H11.

Discussion and implications

This study extends the applicability of Tsitsou’s (2012) brand personality scale to SMEs domain – with particular reference to a developing world. The current study provides relevant insights into how the various dimensions of Tsitsou’s brand personality model directly and indirectly affect customers’ satisfaction with SMEs products and services. The results of the study have shown that competitiveness, prestige, morality, authenticity and credibility had positive direct and indirect influences on customer satisfaction. First, competitiveness had a significant positive correlation with customer satisfaction (H1). The results are consistent with what was found in a study undertaken by Zainuddin, Radzi, and Zahari (2015). It is logical that when SMEs have competitive products and services, they are likely to meet the needs of customers and enhance satisfaction. Second, the results indicated that prestige positively influenced customer satisfaction (H2), this agrees with earlier researchers (Steenkamp et al., 2003). Third, morality had a positive effect on customer satisfaction (H3). If SMEs can support moral values such as honesty, sincerity, and trustworthiness they are likely to influence customer satisfaction (Haidt & Graham, 2007). Fourth, authenticity had a positive association with customer satisfaction (H4); this is consistent with the results of previous studies (Jang et al., 2012). Of note is that if customers perceive SMEs products and services as genuine, they are likely to be satisfied. Fifth, credibility positively influenced customer satisfaction (H5), this is consistent with what Sweeney and Swait (2008) did in their study. As long as customers perceive SMEs products and services as credible then, they are satisfied. Finally, product quality positively influenced customer satisfaction (H6). Results confirm previous findings by Etemad-Sajadi and Rizzuto (2013). Whenever products and services meet the expectations of customers in terms of quality attributes consumers are satisfied.

The mediation hypotheses that brand personality is positively correlated to customer satisfaction through product quality were supported in this research (H7; H8, H9; H10 & H11). This means product quality partially mediated the relationships among competitiveness, prestige, morality, authenticity, credibility and customer satisfaction. These results are similar to previous findings (Chang & Zhu, 2011).

Research implications

Theoretical implications

This study extends the applicability of Tsitsou’s (2012) brand personality scale to SMEs domain – with particular reference to a developing world. According to the knowledge of the researchers, this empirical study is pioneering this domain area by applying Tsitsou’s scale to SMEs. This research provides relevant insights into how the various dimensions of Tsitsou’s brand personality model directly and indirectly affect customers’ satisfaction with SMEs products and services. Thus, adding to the limited extant literature on the role that the brand personality of SMEs may enhance the satisfaction of customers. The study enhances the existing literature by offering a more profound insight into how the brand personality of small and medium-sized enterprises influences consumer satisfaction. The study provides new insights and perspectives to the existing knowledge by examining unexplored aspects of SME brand personality and its influence on customer satisfaction. It reveals how SMEs can improve consumer experiences and loyalty. The study also includes findings from allied areas and compares them with studies in larger businesses to enhance the conversation and provide comparative perspectives. The research broadens the field of investigation and encourages more academic discussion on the relationship between SME brand personality and consumer satisfaction by combining various sources of information and offering new insights. The study enhances the existing literature by addressing gaps in current knowledge, providing new viewpoints, and inspiring future research in the field of SME branding and consumer behaviour. This is useful to scholars who may want to probe the results. One of the most important implications of this study is proof that product quality played the role of a mediation variable between brand personality dimensions and customer satisfaction.

Practical implications

This research stresses the role that Tsitsou’s brand personality dimensions on customer’ satisfaction in SMEs in a developing world. The findings of this study suggest that consumers of SMEs products and services perceive SMEs’ brand personality that is competitive, prestigious, moralistic, authentic and credible. It has also been found that brand personality dimensions have positively impacted customer satisfaction through perceived product quality. It is therefore recommended that business practitioners use these brand personality traits to market their products and services to enhance customer satisfaction. The study provides insight to owners of SMEs that brand personality has to be considered as an indispensable feature that they can employ to improve customer satisfaction, which in turn may attract new customers.

Limitations and future research

This study relies on a cross-sectional design which makes it difficult to infer the results. To have a better comprehension of the association among brand personality dimensions, product quality and customer satisfaction - it is recommended that a longitudinal study be conducted to examine if similar results could be obtained. If such a study is undertaken it would permit the researchers to examine and track the dynamic nature of these relationships. One of the limitations relates to the choice of types of business that the researchers used to carry out this study – studies could also be carried out in other businesses under SMEs in Zimbabwe and beyond. Since this study is the first of its kind (according to the researchers’ knowledge) to be done, more studies could be extended to other areas under SMEs for authentication purposes. The selection of the sample was confined to SMEs that are operating in a small urban – Masvingo. Conversely, to increase the generalisability of the research results further studies could be done where data may be collected from different geographic regions of Zimbabwe. Moreso, the research can be replicated in different sociocultural contexts taking into account the variations in socioeconomic conditions between Masvingo and other provinces in Zimbabwe, and how cultural elements might impact the research results, such as attitudes, behaviours, and reactions to specific stimuli or circumstances. Emphasising cultural sensitivity and considering diversity is crucial when examining human conduct and society.

_brand_personality_scale.png)

_brand_personality_scale.png)