1. Introduction

Entrepreneurs play a crucial role in driving economic growth, job creation, and addressing societal challenges both in the United States and globally (Acs et al., 2018; Audretsch et al., 2021). However, entrepreneurial endeavors often require individuals to mitigate risks, persevere through setbacks, and innovate in the face of uncertainty (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Rauch & Frese, 2007) - qualities that may not be internalized or perceived favorably by all individuals (Cacciotti & Hayton, 2015). Consequently, identifying the factors that contribute to the development of an entrepreneurial identity (EI) is crucial for understanding who may be most suited for entrepreneurial pursuits. Yet, our knowledge of how individual characteristics interact with environmental factors, particularly the degree of rurality, to influence EI formation remains limited. Further, this lack of information hinders the extent to which entrepreneurship can be fostered across diverse geographic contexts, particularly rural environments, which present unique challenges and opportunities (Hart et al., 2005).

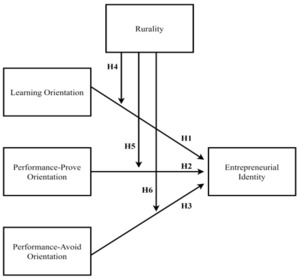

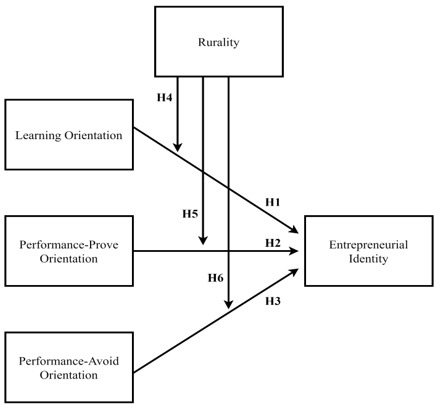

To address this critical issue, we adopt a theoretical approach that integrates two previously proposed perspectives suggested by entrepreneurship scholars (Mmbaga et al., 2020; Powell & Baker, 2014; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021). Using this approach as a guide, we examine individuals’ dispositional goal orientations as predictors of EI and investigate conditions under which they are more and less likely to enhance EI formation. Specifically, we consider the impact of three goal orientations (i.e., learning, performance-prove, performance-avoid), and their interaction with the rurality of individuals’ geographic regions in contributing to EI. Conceptualizing rurality on a continuum, we define the construct as the extent to which individuals live in an area characterized by low population density, limited urban development, and distance from major cities. That is, rather than establishing an unnecessary rural vs. urban dichotomy, our approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the lived experience of rurality, which can vary even within officially designated rural areas (Hart et al., 2005), and aligns with our focus on individuals’ perceptions of their environment. Crucially, while recent research suggests that rurality may not directly predict EI, it indicates that rurality can exert conditional effects (Barber et al., 2023). Thus, we investigate the extent to which rurality moderates the association between goal orientations and EI.

Our contributions are fourfold. First, we consider the interaction of personal trait-like (i.e., dispositional goal orientations) and situational (i.e., degree of rurality) factors in the development of EI. Past work has largely ignored the joint effects of personal and situational characteristics in the same model, despite both likely playing a critical role in the development of individuals’ EI (Barber III et al., 2023). Additionally, three reviews of the EI literature have called for more research focusing on contextual variables (Jones et al., 2019; Mmbaga et al., 2020; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021). Entrepreneurs operate in diverse environments, even within a single nation or state (e.g., rural vs. urban), and these distinct contexts can provide varied experiences and opportunities that influence EI formation.

Second, we address VandeWalle and colleagues’ (2019) call to examine moderators of goal orientations to better understand how subsequent perceptions are impacted. By investigating the extent to which rurality moderates the association between individuals’ goal orientations and EI, we identify conditions under which the effects of goal orientations on EI are more and less pronounced.

Third, we synthesize conceptual and empirical work on goal orientations from multiple literatures, including social, educational, and industrial-organizational psychology, and integrate this information into our discussion of EI. We consider research on the socio-cognitive underpinnings of goal orientations (e.g., Kaplan & Maehr, 2007), roles (e.g., McCall & Simmons, 1978), and social perceptions (e.g., Tajfel, 1982) to more comprehensively explain the conditions under which EI is likely to form. This approach allows us to answer the following questions: What relatively stable, personal, and motivation-related characteristics are likely to contribute to EI formation, and under what circumstances are these characteristics particularly impactful? Also, to what extent do goal orientations and their interactive effects with rurality influence EI above and beyond previous research?

Identifying dispositional antecedents’ direct and conditional effects on EI can ultimately extend insight into future decision-making, venture strategies, and firm outcomes (e.g., Miller & Le Breton–Miller, 2011; Mmbaga et al., 2020), in addition to informing the development of more effective vocational counseling and training programs. Moreover, understanding the predictive utility of goal orientations may be pragmatically helpful for creating interventions designed to maximize their beneficial effects and minimize potential drawbacks (Vandewalle et al., 2019).

Fourth, we address a significant limitation of prior goal orientations research. As noted by VandeWalle and colleagues (2019), “The overwhelming bulk of goal orientations research has occurred in academic settings with students” (p. 139). Our research investigates goal orientations and their impact on EI across two studies, both sampling from non-student, full-time employees. While this context is highly relevant to the pursuit and attainment of goals, particularly as it pertains to the formation of EI, it has been largely ignored in past research.

2. Theoretical Development and Hypotheses

To explain the formation of EI, we integrate theoretical perspectives on social and role identity (Alsos et al., 2016; Mathias & Williams, 2017) while incorporating research on goal orientations. The social identity perspective posits that individuals develop their sense of self through social comparisons and self-categorization processes (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987), suggesting that EI formation is influenced by individuals’ perceptions of similarity to prototypical entrepreneurs and their aspirations to belong to this social group (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Powell & Baker, 2014). Additionally, role identity theory emphasizes how different entrepreneurial roles (e.g., innovator, developer) shape individuals’ perceptions and behaviors (Mathias & Williams, 2017; Mmbaga et al., 2020), suggesting that both broader social group norms and specific role expectations jointly influence EI formation.

To enrich our framework, we incorporate research on goal orientations, which suggests that individuals adopt different orientations towards achievement situations, influencing their cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses (Dweck, 1986; Elliot & Church, 1997). Notably, dispositional goal orientations represent relatively stable individual differences, and represent how people approach, interpret, and respond to achievement contexts (VandeWalle, 1997). We propose that these orientations (i.e., learning, performance-prove, performance-avoid) play a significant role in EI development by guiding individuals’ interpretation of social events and promoting specific patterns of cognition and behavior (Ames, 1992; Elliott & Dweck, 1988). Specifically, we contend that these goal orientations complement existing identity approaches by providing greater insight into the motivational underpinnings driving EI formation. As such, they allow for a more nuanced conceptual understanding of why some individuals may be more predisposed to developing a strong EI. This integrated approach aligns with recent calls in the literature to consider both individual and contextual factors contributing to EI (Jones et al., 2019; Mmbaga et al., 2020; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021), as well as research emphasizing the importance of considering both personal trait-like characteristics and situational factors to further elucidate the conditions under which individuals are likely to hold more or less of an EI (Barber III et al., 2023).

2.1. Dispositional Goal Orientations

We define goal orientations as general patterns of cognition and action tied to the pursuit of achievement goals (Yeo et al., 2009). While early research focused primarily on adolescents’ learning and performance orientations in educational settings (e.g., Bandura & Dweck, 1985; Nicholls et al., 1989), later work expanded to include adult populations in organizational contexts (Vandewalle et al., 2019). The most widely accepted three-factor model encompasses learning, performance-prove, and performance-avoid orientations (VandeWalle, 2003; Vandewalle et al., 2019). A learning goal orientation focuses on developing knowledge and skills, while performance-prove and performance-avoid orientations emphasize attaining favorable and avoiding unfavorable competence judgments, respectively (Brett & VandeWalle, 1999; Dweck, 1986; Hirst et al., 2011).

Although some scholars have conceptualized both approach and avoid factors for mastery goals (e.g., Elliot, 1999), a three-factor model without the mastery-avoid factor has been predominantly used in published research (Vandewalle et al., 2019). We adopt this three-factor model in our study, as it allows for greater examination and integration of existing literature. Furthermore, we focus on dispositional goal orientations, which capture generally stable patterns of cognition and action across situations (Nicholls, 1992; Yeo et al., 2009). These differ from state-focused and domain-specific orientations (DeShon & Gillespie, 2005), which provide less clarity surrounding the enduring motivational tendencies likely to influence individuals’ behavioral patterns across contexts.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Identity

In this research, we examine these dispositional goal orientations as antecedents of EI. Relatedly, our conceptualization of EI refers to a broad, self-perceived, and internalized role that allows individuals to understand the social meaning of being an entrepreneur. Drawing from social identity theory, individuals with a stronger EI perceive themselves as similar to prototypical entrepreneurs and seek to adopt corresponding characteristics and behaviors (Stets & Burke, 2000; Zuzul & Tripsas, 2020). This identity formation process involves both role-related self-realization and interactions between the self and society (McCall & Simmons, 1978; Wry & York, 2017).

Understanding EI is crucial due to its significant impact on entrepreneurial outcomes and behaviors. Research has consistently shown that EI is a strong predictor of entrepreneurial intentions and actions (Brändel et al., 2018; Obschonka et al., 2015). Moreover, EI has been linked to various key outcomes that contribute to entrepreneurial success. For instance, entrepreneurs with a strong EI are more likely to identify and pursue innovative business opportunities (Farmer et al., 2011). A well-developed EI has also been linked to higher levels of venture growth and success (Sieger et al., 2016; Zuzul & Edmondson, 2017).

Beyond opportunity recognition and venture growth, EI plays a vital role in sustaining entrepreneurial efforts. Entrepreneurs with a strong EI demonstrate greater resilience in the face of setbacks and are more likely to persist in their entrepreneurial endeavors (Cardon & Kirk, 2015; Muñoz & Cohen, 2018). Relatedly, a greater EI has been suggested to increase passion for entrepreneurial activities and commitment to one’s venture (Cardon et al., 2009; Collewaert et al., 2016).

Extant research on the antecedents of EI has generally focused on two specific types of motivation (Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021). That is, researchers have established that starting a business may be due to either intrinsic (e.g., Ekinci et al., 2020) or extrinsic (e.g., Vesala & Vesala, 2010) factors. However, it should be noted that individuals’ motivations are often facilitated by their dispositional characteristics (e.g., Newman et al., 2019; Winter et al., 1998), which once identified, can provide insight into who is more likely to adopt or internalize a particular career path (e.g., Allen, 2003; Engel et al., 2017; Woo, 2011). Notably, self-set goals have been found to explain the impact of multiple dispositional characteristics (e.g., Gielnik et al., 2018; Locke & Latham, 2002). Thus, we contend that goal orientations may play a key role in promoting or inhibiting the formation of EI.

2.3. Learning Goal Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity

We propose that learning goal orientation (LGO) plays a significant role in the formation of EI. LGO refers to an individual’s tendency to focus on developing knowledge and mastering skills in pursuit of achievement goals (Brett & VandeWalle, 1999; Dweck, 1986; Gong et al., 2017; Hirst et al., 2011). This orientation is characterized by a motivation for self-improvement, suggesting a greater comfortability with taking risks that allow for personal growth (Burnette et al., 2020; Hirst et al., 2011).

Specifically, individuals with a higher LGO construct mental schemas that frame challenges and potential failures as learning opportunities rather than threats to their competence (Dweck, 1986; Hirst et al., 2009). These cognitive frameworks align closely with the entrepreneurial process, which often involves managing risk and uncertainty. Consequently, those with a higher LGO should be more likely to embrace entrepreneurial challenges as perceived developmental opportunities (Newman et al., 2019).

As individuals with a strong LGO engage in entrepreneurial activities, they may perceive similarities between their desire for personal growth and the continuous learning required in entrepreneurial roles (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Powell & Baker, 2014). Through this engagement, they can incorporate aspects of the entrepreneurial role into their self-concept, strengthening their EI (Mathias & Williams, 2017; Mmbaga et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the socio-cognitive processes associated with LGO, such as seeking feedback and learning from others (Cho, 2013; Gong et al., 2017; Teunissen et al., 2009), can facilitate EI development through increased exposure to entrepreneurial norms, values, and practices. This proactive learning approach may contribute to a stronger identification with the entrepreneurial community, further reinforcing individuals’ EI.

Thus, we propose that LGO plays a key role in promoting EI formation. Those with a higher LGO are likely to hold a stronger EI, as they demonstrate a greater dispositional drive to acquire knowledge, develop skills, and frame situations as opportunities for growth (Vandewalle et al., 2019). The entrepreneurial journey, characterized by continuous learning, adaptation to change, and navigation of complex business environments (Mmbaga et al., 2020; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021), aligns well with the desire for development that characterizes individuals with a strong LGO.

Hypothesis 1: Learning goal orientation will be positively associated with entrepreneurial identity.

2.4. Performance-Prove Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity

Performance-prove orientation (PPGO) refers to an individual’s general drive to demonstrate competence and attain favorable judgments in pursuit of achievement goals (Brett & VandeWalle, 1999; Hirst et al., 2011). We propose that PPGO plays a significant role in shaping EI formation. Individuals with a high PPGO construct mental schemas that frame achievement situations as opportunities to showcase their abilities and gain recognition (Elliot & Church, 1997). These cognitive frameworks align well with entrepreneurial contexts, which often provide visible platforms for demonstrating competence and achieving success (Kanze et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2005). Consequently, those with a higher PPGO may be more likely to internalize the entrepreneurial role, viewing it as a viable path to attain desired outcomes of success and validation.

The socio-cognitive processes associated with PPGO can facilitate EI development through social comparison and self-categorization mechanisms (Turner et al., 1987; Wry & York, 2017). As individuals with a pronounced PPGO engage in entrepreneurial activities, they may perceive similarities between their desire for competence demonstration and the prototypical behaviors of successful entrepreneurs. This perceived congruence can reinforce their goals and promote the integration of entrepreneurial values and behaviors into their self-concept (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Powell & Baker, 2014).

Furthermore, the desire for consistency between self-concept and social group identities (Hornsey, 2008; Zagefka, 2021) may motivate high PPGO individuals to actively seek out entrepreneurial networks and role models (Hoggy & Terry, 2000; Karimi et al., 2014). This proactive approach to affiliation can enhance their EI through increased exposure to and identification with others who embody entrepreneurial values and behaviors, further reinforcing their entrepreneurial self-concept.

While individuals with a higher PPGO may be drawn to entrepreneurship for its potential rewards and recognition, those with lower PPGO might find the inherent risks and uncertainties less appealing, potentially limiting their EI development. The entrepreneurial journey, which can provide greater visibility and the potential for both public success and failure, aligns more closely with the motivational tendencies of higher PPGO individuals (Nowiński & Haddoud, 2019).

Hypothesis 2: Performance-prove orientation will be positively related to entrepreneurial identity.

2.5. Performance-Avoid Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity

A performance-avoid goal orientation (PAGO) refers to an individual’s tendency to focus on avoiding unfavorable competence judgments (Brett & VandeWalle, 1999; Hirst et al., 2011; Janssen & Prins, 2017). Individuals with a high PAGO construct mental schemas that frame achievement situations as potential threats to their competence. Given the inherently risky nature of entrepreneurship and the prevalence of setbacks, those with a higher PAGO may be reluctant to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Newman et al., 2019; Silver et al., 2006). Specifically, these individuals are highly motivated to avoid failure and negative evaluations, which are often at odds with the entrepreneurial process.

Further, based on social comparison and self-categorization processes, PAGO is likely to stifle EI development. As individuals with a higher PAGO encounter entrepreneurial contexts and opportunities, they may perceive discrepancies between their desire to avoid negative judgments and the risk-taking behaviors that characterize successful entrepreneurs. These perceptions can hinder the adoption of entrepreneurial values and behaviors into their self-concept (Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Powell & Baker, 2014).

Furthermore, the fear of failure characteristic of PAGO may lead individuals to distance themselves from entrepreneurial roles. Pertinently, those higher in PAGO tend to seek less performance-related feedback (VandeWalle & Cummings, 1997) and engage in less proactive behavior conducive to self-development (Gong et al., 2017; Porath & Bateman, 2006). This tendency to avoid potentially negative information about their competence may limit their exposure to and identification with entrepreneurial norms, values, and practices, further inhibiting EI formation.

The entrepreneurial journey often requires perseverance and learning through failure (Kollmann et al., 2017). However, individuals with high PAGO may view such experiences as threats to their self-concept rather than opportunities for growth. This mindset is at odds with the resilience and adaptability often required in entrepreneurial contexts (Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021), suggesting that high PAGO individuals will disengage from entrepreneurial roles and identities.

Hypothesis 3: Performance-avoid orientation will be negatively associated with entrepreneurial identity.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Rurality

2.6.1. On the Learning Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity Relationship

We propose that the extent to which individuals live in a rural location is likely to moderate the relationship between LGO and EI. Rural environments present distinct characteristics that may intensify the effects of LGO on EI formation. For instance, rural areas may face unique economic challenges and market gaps due to their geographic isolation and limited resources (Korsgaard et al., 2015). For individuals with a high LGO, these challenges represent prime opportunities for learning and innovation. The need to develop creative solutions to address local needs aligns strongly with the LGO drive for skill acquisition and problem-solving, potentially reinforcing identification with the entrepreneurial role more strongly than in urban settings.

Moreover, the potential presence of less formal educational and professional development opportunities in rural areas (Paddock & Marsden, 2015) may elevate the appeal of entrepreneurship as a vehicle for self-directed learning. Notably, this context necessitates proactive, independent knowledge acquisition – a hallmark of high LGO individuals. As such, rural entrepreneurship may be perceived as an ideal path for personal growth, strengthening the link between LGO and EI.

Rural communities typically feature stronger social cohesion and increased community involvement (Jack & Anderson, 2002). For LGO individuals, this environment offers a unique laboratory for acquiring tacit knowledge about local markets, customer needs, and business practices, further enhancing the attractiveness of an EI. Further, rural areas often foster a culture of resourcefulness and innovation born out of necessity (Müller, 2016; Pato & Teixeira, 2018). These environments may require unique aspects of adaptation and creative problem-solving that resonate strongly with the LGO-related preference for challenging situations that promote learning. Thus, the simultaneous presence of a high LGO and highly rural environment may strengthen individuals’ identification with entrepreneurship.

Along this line of thinking, rural entrepreneurship frequently demands a more versatile skill set due to limited access to specialized services (Roundy, 2017). For LGO individuals, the opportunity to develop expertise across various business functions is likely to further reinforce their EI. Consequently, as the degree of rurality increases, environmental characteristics are likely to interact synergistically with a high LGO, amplifying its positive effects on EI formation.

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between learning goal orientation and entrepreneurial identity will be moderated by rurality, such that the positive association will become stronger when rurality is high.

2.6.2. On the Performance-Prove Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity Relationship

We propose that rurality is also likely to moderate the relationship between PPGO and EI in a manner that intensifies their positive association. Rural areas typically offer limited traditional employment opportunities (Paddock & Marsden, 2015), potentially elevating the appeal of entrepreneurship for high PPGO individuals. In this context of scarce alternatives, entrepreneurship may be perceived as an ideal avenue for demonstrating competence and achieving success, aligning strongly with PPGO motivations (Elliot & Church, 1997).

The closer social ties and increased visibility of individual actions in rural communities (Jack & Anderson, 2002) create a unique social stage for high PPGO individuals. This heightened social scrutiny may serve as a powerful motivator, as entrepreneurship offers a visible platform for gaining recognition and status. While rural areas may have fewer entrepreneurs, those who succeed often achieve greater local prominence (Müller, 2016). This increased potential for local impact and recognition may be particularly appealing to high PPGO individuals, offering a clear path to demonstrating their abilities. Specifically, the prospect of becoming a highly visible, successful figure in their community may contribute to a more enhanced EI.

Furthermore, given that rural environments often present distinct challenges due to geographic isolation (Korsgaard et al., 2015; Zahra & Wright, 2016), they may provide salient opportunities for high PPGO individuals to showcase problem-solving skills. The prospect of visibly addressing community needs could significantly reinforce their identification with the entrepreneurial role. Furthermore, the strong traditions of self-reliance and independence often found in rural areas (Hofstede, 2001) align well with entrepreneurial values. For high PPGO individuals, embracing entrepreneurship in such contexts may be seen as embodying these valued traditions, further strengthening their EI. Therefore, when rurality is high, environmental characteristics are likely to interact synergistically with a high PPGO, bolstering its positive influence on EI formation.

Hypothesis 5: The relationship between performance-prove orientation and entrepreneurial identity will be moderated by rurality, such that the positive association will become stronger when rurality is high.

2.6.3. On the Performance-Avoid Orientation and Entrepreneurial Identity Relationship

Rural areas typically offer a more limited economic landscape with fewer resources and opportunities (Paddock & Marsden, 2015). For individuals with high PAGO, who are primarily motivated to avoid failure and negative evaluation (Elliot & Church, 1997), this scarcity may significantly amplify their perceptions of and comfortability with risk pertaining to entrepreneurship. The closer social ties and increased visibility of individual actions in rural communities (Jack & Anderson, 2002) create conditions that may be particularly challenging for high PAGO individuals. The visibility of failure within a smaller, tightly knit community could exacerbate concerns about negative judgments, further deterring identification with the entrepreneurial role.

Additionally, because rural areas often lack economic diversity (Fortunato, 2014; Müller, 2016), they may be perceived to only offer entrepreneurial opportunities that are aligned with highly distinct skill sets. These perceived limitations could increase the concerns of high PAGO individuals about potential failure in entrepreneurship. Additionally, the more traditional mindsets that can often be found in rural settings (Hofstede, 2001) may reinforce risk-averse tendencies, making entrepreneurship seem less normatively acceptable and stifling EI formation for those with high PAGO.

Moreover, the typically fewer entrepreneurial support systems in rural areas (Roundy, 2017) may pose a significant barrier for high PAGO individuals. This perceived lack of supportive infrastructure could heighten their concerns about potential challenges and increase their reluctance to view themselves as entrepreneurs. The absence of readily available resources and support networks may augment the perceived risks associated with entrepreneurship, further inhibiting EI development. Figure 1 highlights our proposed theoretical model.

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between performance-avoid orientation and entrepreneurial identity will be moderated by rurality, such that the negative association will become stronger when rurality is high.

3. Method

3.1. Samples and Data Collection Procedures

We conducted two studies using online surveys with full-time employees across the United States. Study 1 (n=377) used Prolific (e.g., Barber III et al., 2023), while Study 2 (n=405) employed the CloudResearch online platform (e.g., Hartman et al., 2023). Participants were compensated $3 and $4 respectively. Study 2 was conducted to assess the extent to which Study 1’s findings could be replicated, in addition to measuring rurality so that our moderation hypotheses could be tested. While Study 1 collected all measures in a cross-sectional manner, Study 2 improved on this limitation via a time-lagged design. Specifically, all variables except EI were measured at Time 1, and EI was assessed via a separate online survey approximately one week later (i.e., Time 2). This one-week lag was orchestrated to mitigate common method bias, establish temporal precedence, avoid priming effects, and maintain participant retention while still benefiting from a lagged design (Lavrakas, 2008; Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010; Podsakoff et al., 2003; Reis & Judd, 2014). Both studies required participants to be at least 18 years old, and individuals were not prescreened to identity as entrepreneurs, as this would unnecessarily limit variability in our outcome variable.

In Study 1, participants averaged 46.3 years old (49.7% female). Approximately 38.0% held a bachelor’s degree, 18.3% held a master’s degree, and 5.7% held a doctoral or professional degree. Participants identified as White (68.8%), Black/African American (12.7%), Asian/Pacific Islander (8.7%), Hispanic/Latino (6.1%), American Indian/Native American (1.1%), or Other (2.6%). Moreover, Study 2 participants averaged 41.9 years old (38.8% female). About 43.2% held a bachelor’s degree, 17.3% held a master’s degree, and 6.4% held a doctoral or professional degree. Study 2 respondents identified as White (64.9%), Black/African American (10.9%), Asian/Pacific Islander (8.9%), Hispanic/Latino (12.8%), American Indian/Native American (1.0%), or Other (1.5%). Both studies implemented measures to ensure data quality, including the use of high approval rating requirements, the inclusion of attention check items, the tracking of IP addresses to prevent duplicate responses, and the assurance of confidentiality to participants.

3.2. Measures

Dispositional Goal Orientations. LGO (8 items), PPGO (6 items), and PAGO (7 items) were assessed using Attenweiler and Moore’s (2006) scales in both studies. Participants rated their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Example items include: “I prefer to work on tasks that force me to learn new things” (LGO), “I prefer to work on projects in which I can prove my ability to others” (PPGO), and “I prefer to avoid situations in which I might perform poorly” (PAGO). In Study 1, reliabilities were α = .93 (LGO), α = .92 (PPGO), and α = .78 (PAGO). In Study 2, reliabilities were α = .94 (LGO), α = .92 (PPGO), and α = .88 (PAGO).

Entrepreneurial Identity. In both studies, EI was measured via the four-item scale used by Barber and colleagues (2023). Responses ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). An example item is “Entrepreneurship is an important part of who I am”. The reliability was α = .88 in Study 1 and α = .91 in Study 2.

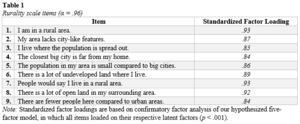

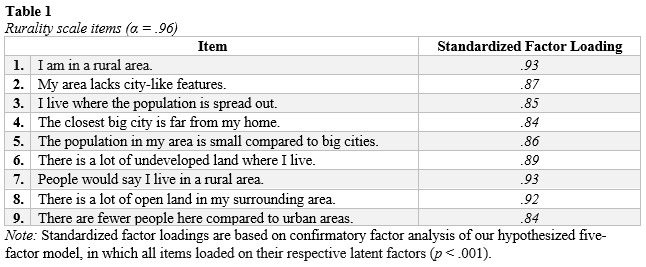

Rurality*.*** In Study 2, we introduced a nine-item self-report scale developed following recommended scale construction procedures (i.e., Colquitt et al., 2019; Hinkin, 1995, 1998). Respondents were asked to rate how much they agreed with statements, on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), about where they live. Table 1 provides the full list of items, along with the scale’s reliability and standardized factor loadings from Study 2.

Covariates. Both studies controlled for age, biological sex, and education level. In Study 2, we also included focus/adaptability (Morris et al., 2013) as a covariate, given its established significance as a predictor of EI in previous research (Barber et al., 2023). This approach allowed us to determine whether our proposed variables predicted incremental variance in EI beyond previously identified demographic and dispositional characteristics.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

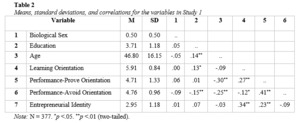

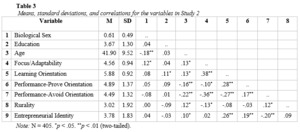

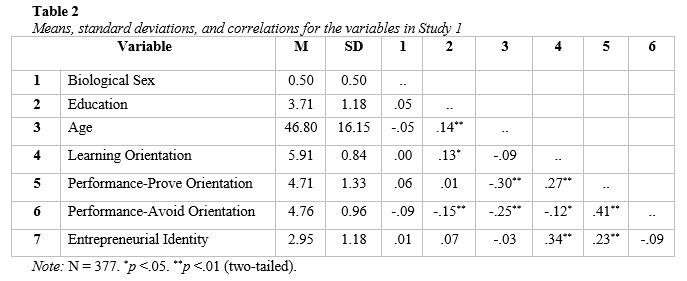

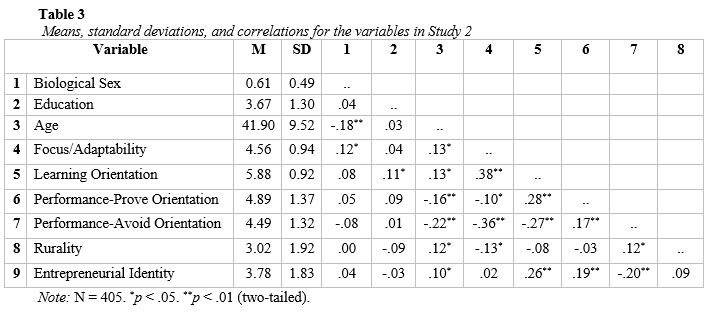

Tables 2 and 3 highlight the descriptive statistics and correlations from Study 1 and 2, respectively. In preliminary support of predictions, LGO was positively associated with EI in Study 1 (r = .34, p < .01) and Study 2 (r = .24, p < .01). Further, PPGO was positively correlated with individuals’ EI in Study 1 (r = .23, p < .01) and Study 2 (r = .18, p < .01).

Additionally, confirmatory factor analyses were performed in Study 2 to assess the hypothesized factor structure of the measurement model in comparison to alternatives. Fit indices and Chi-square difference tests were reported to demonstrate whether the proposed measurement model fit the data appropriately. Specifically, LGO, PPGO, PAGO, rurality, and EI were expected to load on five different factors, and this factor structure was expected to provide a better fit to the data than an alternative four-factor model in which LGO and PPGO loaded on the same factor. Additionally, our hypothesized five-factor model was expected to provide a better fit than an alternative unidimensional model in which all constructs were combined into a single factor. Consistent with expectations, results demonstrated that the hypothesized model provided a significantly better fit to the data (χ2 (N = 405; df = 517) = 1945.02, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.89) than the alternative four-factor (χ2 (N = 405; df = 521) = 3570.68, SRMR = 0.11, CFI = 0.76, Δχ2 (N = 405; Δdf = 4) = 1625.66, p < .001) and unidimensional (χ2 (N = 405; df = 527) = 10152.29, SRMR = 0.25, CFI = 0.26, Δχ2 (N = 405; Δdf = 10) = 8207.27, p < .001) models. Taken together, results provided support for the discriminant validity of our self-report measures.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

Hypotheses were tested via path analysis in Mplus 8.8, using maximum likelihood estimation. Hypothesis 1 predicted that LGO would be positively related to EI which was supported in Study 1 (unstandardized estimate = .37, SE = .07, p < .001) and Study 2 (unstandardized estimate = .34, SE = .11, p < .01). Consistent with our expectations, we found that as individuals’ LGO increased (decreased), the extent to which they held an EI tended to increase (decrease).

Hypothesis 2 proposed that PPGO would positively predict EI, which was supported in both Study 1 (unstandardized estimate = .20, SE = .05, p < .001) and Study 2 (unstandardized estimate = .18, SE = .07, p < .01). As individuals’ PPGO increased (decreased), the degree to which they held an EI typically increased (decreased).

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, we expected that PAGO would be negatively associated with one’s EI. Results provided support for this prediction in Study 1 (unstandardized estimate = -.17, SE = .07, p < .05) and Study 2 (unstandardized estimate = -.21, SE = .07, p < .01). As individuals’ PAGO increased (decreased), the extent to which they held an EI tended to decrease (increase). Taken together, dispositional goal orientations predicted a significant amount of incremental variance (p < .01) in EI (Study 1 ∆R2 = .14, Study 2 ∆R2 = .13) beyond the included control variables. Specifically, for Study 1, goal orientations predicted an additional 14% of the variance in EI beyond the effects of individuals’ age, biological sex, and education level. For Study 2, dispositional goal orientations explained an additional 13% of the variance in EI beyond individuals’ age, biological sex, education, and their level of focus/adaptability.

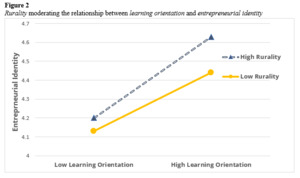

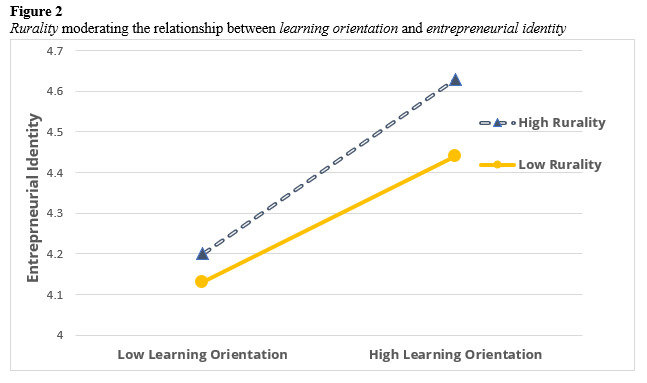

Hypotheses 4–6 were assessed in Study 2, which included our measure of rurality. Specifically, Hypothesis 4 predicted that rurality would moderate the relationship between LGO and EI, such that when rurality was high, the positive association would be stronger. As predicted, there was a statistically significant interaction between LGO and rurality in predicting EI (unstandardized estimate = .10, SE = .05, p < .05), and a plot of the simple slopes demonstrated that the form of the interaction was as hypothesized (see Figure 2). Notably, those living in highly rural areas while demonstrating a high LGO tended to hold more enhanced entrepreneurial identities (+1SD: unstandardized estimate = .54, SE = .14, p < .001), supporting Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that the relationship between PPGO and EI would be moderated by rurality, such that the positive association would be stronger when rurality was high. This hypothesis was not supported (unstandardized estimate = .02, SE = .03, p > .05. In other words, rurality did not significantly influence the relationship between PPGO and EI.

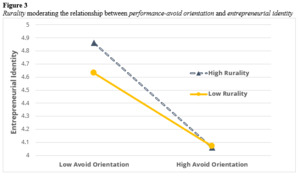

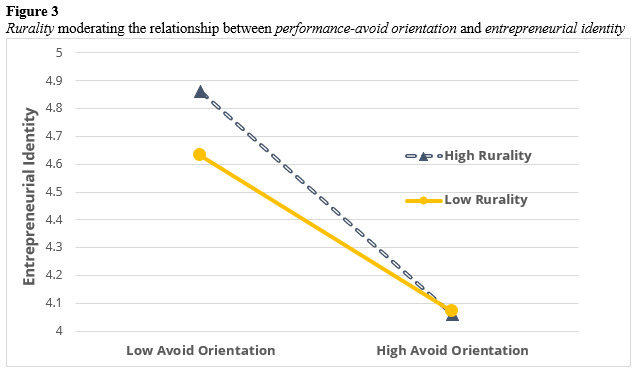

Hypothesis 6 predicted that the relationship between PAGO and EI would be moderated by rurality, such that when rurality was high, the negative relationship would become stronger. Consistent with expectations, there was a statistically significant interaction between PAGO and rurality in predicting EI (unstandardized estimate = -.09, SE = .03, p < .01), and the form of the interaction was as expected (see Figure 3). That is, individuals residing in highly rural areas showed a stronger negative relationship between PAGO and EI. Specifically, those with lower levels of PAGO in highly rural areas tended to hold greater entrepreneurial identities compared to those with higher levels of PAGO in the same areas (+1SD: unstandardized estimate = -.38, SE = .09, p < .001), supporting Hypothesis 6. Additionally, for both Study 1 and Study 2, the results of our hypotheses tests were similar regardless of whether any control variables were included in the analyses.

5. Discussion

Our research bridges goal orientations and EI literature, examining conditions that influence their relationship. Using a socio-cognitive framework integrating identity perspectives with goal orientations research, we found support for five of our six hypotheses. Goal orientations significantly predicted EI formation, with rurality moderating the LGO–EI and PAGO–EI relationships, but not the PPGO–EI association.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to the EI literature in several important ways. First, by integrating goal orientations research with social and role identity perspectives, we offer a more nuanced theoretical understanding of the psychological drivers underlying EI formation. Our findings demonstrate that individuals’ dispositional goal orientations (i.e., LGO, PPGO, PAGO) significantly influence the degree to which they develop an EI. Notably, while LGO and PPGO positively predict EI, PAGO negatively predicts EI. These results extend previous work on EI’s antecedents (e.g., Barber III et al., 2023; Mmbaga et al., 2020; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021) by highlighting the role of trait-like motivational orientations in shaping individuals’ self-perceptions as entrepreneurs. Furthermore, our research demonstrates the utility of goal orientations in predicting EI beyond the effects of focus/adaptability, which has been previously identified as a significant determinant of EI (Barber III et al., 2023). This finding underscores the unique contribution of goal orientations to our understanding of EI formation, suggesting that these dispositional traits play a distinct and important role in shaping entrepreneurial self-perceptions.

Second, we address the call for more research on contextual variables in EI formation (Barber III et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2019; Mmbaga et al., 2020; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2021)) by examining the moderating role of rurality. The significant interactions between goal orientations and rurality underscore the importance of considering both personal and situational factors in EI development. Our findings reveal that the positive effects of LGO on EI are amplified in more rural contexts, while the negative effects of PAGO are exacerbated. This contextual nuance enriches our understanding of how environmental factors can shape the relationship between individual dispositions and EI.

Third, by sampling from non-student, full-time employees, our research addresses the call of scholars (Vandewalle et al., 2019) to further demonstrate the relevance of goal orientations beyond academic settings, and especially as they pertain to adult populations in organizational contexts. As such, we help to elucidate specific conditions under which they are more and less likely to impact the broader domain of identity as it pertains to entrepreneurship.

Finally, our integrative theoretical approach, which synthesizes socio-cognitive underpinnings of identity perspectives and goal orientations literature, provides a more nuanced understanding of EI formation. Specifically, we offer a more comprehensive theoretical explanation of how individuals’ motivational tendencies interact with social and role-based factors to shape entrepreneurial self-perceptions.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings may have several important practical implications for organizations, individuals, and policymakers, particularly in the context of rural economic development. Developing an understanding of which individuals are likely to hold more or less of an EI can provide valuable information for developing more applicable vocational counseling and training programs. Given that EI contributes to important entrepreneurial behaviors and organizational outcomes, including firm performance (de la Cruz et al., 2018; Iyortsuun et al., 2019; Mmbaga et al., 2021), understanding the salient identities likely to be adopted by specific individuals can contribute to the implementation of more effective initiatives.

Notably, our results suggest that interventions aimed at fostering entrepreneurial identities should consider individuals’ goal orientations. Programs designed to promote entrepreneurship might be more effective if tailored to appeal to different motivational orientations. For instance, initiatives emphasizing learning and skill development may be particularly effective for individuals high in LGO, especially in rural areas. Additionally, highlighting calculated risk-taking and resilience in the face of setbacks might resonate more with individuals low in PAGO. Such tailored approaches could capitalize on the greater willingness of low PAGO individuals to engage with challenges, potentially enhancing their EI formation.

Additionally, entrepreneurship promotion efforts in rural areas might be more impactful if they emphasize opportunities for learning, aligning with the amplified positive effects of LGO in these contexts. Rural development agencies and policymakers could leverage this insight to design targeted programs that not only provide resources and training, but also appeal to the motivational orientations that are most conducive to EI formation in rural settings. This may be particularly important in rural communities offering limited formal training on critical topics like exit strategies and succession planning (Crawford & Barber, 2020). By focusing on cultivating entrepreneurial identities through goal orientation-aligned initiatives, rural areas have the potential to foster a more robust entrepreneurial ecosystem, potentially contributing to increased business creation, job growth, and economic diversification. Moreover, initiatives in rural areas should also address the heightened negative impact of PAGO on EI, perhaps by providing additional support via risk mitigation trainings that could reduce perceived barriers to entrepreneurship.

Relatedly, our research informs the development of more effective vocational counseling and training programs, which can be crucial for rural workforce development (Dabson, 2001; Lyons, 2015). By understanding the role of goal orientations in EI formation, individuals can be guided toward careers and entrepreneurial paths that better align with their motivational tendencies. This tailored approach could facilitate the development of more successful and satisfying entrepreneurial careers, potentially increasing retention. Programs may also benefit from the inclusion of mentorship opportunities, as research demonstrates that interactions with mentors contributes to the extent to which individuals define themselves as entrepreneurs (Byrne et al., 2019; Falck et al., 2012; Smith & Woodworth, 2012).

Taken together, interventions could be designed to identify, develop, and allocate resources to those who internalize adoption of the broad entrepreneurship role, potentially creating a future network of local entrepreneurial role models. Pertinently, given that resources in rural areas may be limited (Pato & Teixeira, 2016; Roundy, 2017), organizations and policymakers may benefit from allocating existing educational and developmental resources more efficiently. Through targeted interventions, based on individuals’ goal orientations and rural context, stakeholders might design more effective and resource-efficient programs to foster entrepreneurship.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While our multi-study paper makes significant contributions to existing literature, it is important to acknowledge limitations and outline directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of our Study 1 data limits the inferences that can be made. Although Study 2 improved on this design via a time-lagged approach, future field studies in this domain may benefit from longitudinally investigating how the relationships between our variables evolve over more prolonged periods of time (Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010).

Second, given that all our respondents lived in the United States, future work may benefit from investigating the degree to which our results generalize to different populations. Relatedly, while we focused on rurality as a moderator, future research should consider additional contextual factors that might influence the relationship between goal orientations and EI. For example, goal orientations may be more likely to predict EI based on specific societal resources, opportunities, or constraints. Given that our theory suggests that EI is, in part, based on a self-comparison to existing groups, cultural norms may help shape the degree to which one’s EI develops (Barrett & Vershinina, 2017; Jones et al., 2019; Mmbaga et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2013; Radu-Lefebvre et al., 2020; Vesala & Vesala, 2010).

Third, our studies relied on self-reported measures, which may be subject to common source bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Future research could incorporate multiple data sources or objective measures to further validate our findings. Lastly, although we examined the direct effects of goal orientations on EI and the moderating role of rurality, future studies could also investigate the mechanisms through which these relationships operate. Exploring potential mediators such as entrepreneurial self-efficacy, opportunity recognition, or risk perception could provide deeper insights into the process of EI formation (Shepherd et al., 2015). Future research could also consider why rurality did not moderate the PPGO–EI relationship as hypothesized. This could involve examining other potential moderators, as well as mediators that might help to more intricately explain the mechanisms through which PPGO impacts EI.