1. Introduction

While SMEs rely on the expertise of their owners or top managers to navigate competitive environments, these leaders may lack the requisite skills and resources to successfully do so (Dyer & Ross, 2008). Moreover, SME leaders are frequently inundated with day-to-day operational tasks, leaving limited time to conduct research and search for solutions to strategic issues (Santamaría et al., 2009). Hence, in many cases, these owner/managers turn to external sources of expertise and advice particularly when the performance of the firm is at stake (Achbah et al., 2024; Miller et al., 2024). Advice seeking serves as an effective way of coping with anxious situations where there is a lack of relevant knowledge and resources (Gino et al., 2012).

There are a wide range of external sources that top managers use to seek advice from including consultants, mentors, partners among others and this behavior is shown to have significant effects on decision making, innovation and firm performance (Garg & Eisenhardt, 2017; Sundaramurthy et al., 2014). In their integrative literature review of CEO advice seeking, Ma, Kor and Seidl (2020) state that while there is extensive literature about the drivers and outcomes of advice seeking, we know very little about the process of advice seeking. Specifically, Ma, et al. (2020) suggest that how advice is utilized after it has been received and determining whether and how to incorporate the guidance into the organization warrants further research.

Many scholars argue that a firm’s absorptive capacity (ACAP), where a firm recognizes the value of new information, assimilates and effectively applies it (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), is the dynamic capability that enables firms to utilize knowledge from outside sources effectively (Zahra & George, 2002). Researchers have suggested that absorptive capacity is critical in linking organizational knowledge with learning and performance (Ahuja & Katila, 2001; Kostopoulos et al., 2011; Lane et al., 2001; Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Tsai, 2001). Hence, we expect that ACAP would be an important link between advice seeking and utilizing knowledge effectively. Some researchers have explored this link. For example, in their study of entrepreneurs, van Doorn, Heyden, and Volberda (2017) found that when top management teams (TMT) combined external advice seeking with absorptive capacity to make sense of the formulated judgments of dissimilar others, they achieved higher entrepreneurial orientation. In the context of SMEs, literature has maintained that ACAP influences performance either directly or in combination (e.g., as an antecedent or mediator) with other behaviors or orientations (Zonooz et al., 2011).

In terms of SMEs and external advice seeking, research has suggested that advisory programs serve as a source of resources to enable firm learning (Un et al., 2010) and help them improve. Much of the research emphasis has been placed on the business advisors’ attempt to encourage SMEs to learn and collaborate (Sawang et al., 2016). In a study of incubator advising, learning capabilities as measured by the firm’s absorptive capacity (ACAP), played a role in startup performance (Vincent & Zakkariya, 2021).

However, more specific research focusing as suggested by Ma et al. (2024) on SME learning utilization from external sources is needed. We propose that the value SME executives place on acquired external knowledge, as well as the process for how the knowledge is integrated into the firm are both critical to whether they address strategic challenges and realize performance improvements. We expect that for any real performance impact to materialize, the SME and its owner/managers must fundamentally be open to learning from others and to implementing their advice. We suggest that while external advice may ultimately have a positive influence on SME performance, the extent to which such support influences performance relies heavily on the SME’s absorptive capacity.

This paper aims to make several contributions to the literature regarding the utilization of advice-seeking for SMEs by exploring the firm’s absorptive capacity. First, we suggest that simplified approaches measuring ACAP obscure the unique dimensions of the learning utilization process required for firms to actually reap performance benefits from external advice. There have been many calls for more precision in absorptive capacity research (Song et al., 2018). However, much research on ACAP often uses simplistic measures, such as R&D intensity (Debrulle et al., 2014), or focuses on one or two dimensions of ACAP (Chaudhary & Batra, 2018). Therefore, we explore ACAP as a dynamic capability with four latent mechanisms; knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation, that manifest themselves as a learning process (Zahra & George, 2002). As this process has been a relatively underexplored area in ACAP research, we work to precisely measure and then elaborate on the process aspects of the construct in the context of advice seeking. Second, studying ACAP’s role in advice seeking requires a stable external learning context to explore the construct and its variations across firms. Hence, we examine ACAP and any resulting performance improvements in the learning context of SMEs engaged in a university consulting experience. While all of the SMEs in our sample participated fully in the consulting engagement, they exhibited varied ACAP capabilities and performance improvements.

We believe our approach provides a deeper exploration of each ACAP mechanism and their interrelationships resulting in a more thorough and meaningful understanding of how external advice is valued and integrated in SMEs. As Ma et al. (2020) state, when examining advice seeking, research implicitly assumes that advice is utilized, however this assumption may not reflect reality. By exploring SME ACAP, we aim to shed further light on advice utilization and the role and influence ACAP mechanisms have on SME learning and performance improvement.

The structure of this paper is as follows. First, we provide a review of the absorptive capacity literature, emphasizing the sequential nature of its dimensions and identifying research gaps in the context of SMEs, business consulting, and performance. Following that, we develop hypotheses based on a four-dimensional model of absorptive capacity. Next, we explain the data and analysis methods employed and test the hypotheses. Finally, we discuss the results of the study and provide practical implications for understanding the learning process during a consulting engagement.

2. Literature Review and Research Gaps

From a learning perspective, managers in low performing organizations search for solutions to firm problems. Organizations often obtain and integrate external information hoping to solve strategic challenges (Winter, 2000). Doing well is contingent on an organization’s absorptive capacity, which refers specifically to a firm’s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge (Zahra & George, 2002). According to Chryssochoidis, Dousious, and Tsoukas (2016) and Teece (2014), this dynamic capability includes an agility to perceive environmental opportunities and threats, learning mechanisms to upgrade resources, and orchestration skills to reorganize processes and effectively deploy resources to increase performance. These four dimensions of absorptive capacity have been theorized as a sequential internal path for gaining and applying knowledge effectively. They are further defined in the section below.

In the ACAP literature, the ability to acquire information has been highlighted and explained as a firm having an Acquisition capacity which is a firm’s capability to locate, identify, evaluate and acquire external knowledge that is critical to the growth of its operations (e.g., Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Zahra & George, 2002). Key to this mechanism is its focus on being able to sift through and prioritize information that might be crucial to key activities and ultimately success.

Second is a firm’s Assimilation capacity which is the skill of a company to understand knowledge (or information) brought in from outside the organization. It involves categorizing, organizing, processing, interpreting, and eventually integrating and grasping new knowledge (see, for instance, Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Szulanski, 1996). Assimilation is about making new information fit existing schemas by adding to the existing knowledge base. The emphasis here is trying to understand the new knowledge gained by relating it to current mental frameworks or perspectives. For SMEs, assimilation is an important aspect of adding new knowledge to the firm without requiring too much challenge or change.

Third, is Transformation capacity which is different from assimilation in that it is activated when acquiring new knowledge that must be interpreted it in novel ways when combining it with that current knowledge base (e.g., Jansen et al., 2005; Todorova & Durisin, 2007). Transformation has been examined in the knowledge transfer process as the challenge of integrating novel or unique knowledge with existing knowledge (Carlile & Rebentisch, 2003). It is important to note that not all new external knowledge requires transformation when its novelty is low or common. However, in cases where there is amplified novelty and specialization, participants must have organizational processes and time for interpreting and recalibrating knowledge into relevant domains (Carlile & Rebentisch, 2003).

Exploitation capacity is a firm’s ability to incorporate the knowledge acquired, assimilated and transformed in its operations and routines for the firm’s application and use. This capability leads to the development or improvement of new products, systems, processes, organizational forms, and competencies (e.g., Lane et al., 2001; Zahra & George, 2002).

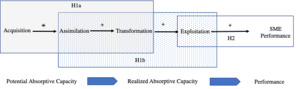

In exploring the four dimensions of absorptive capacity and their relationship to firm performance, Ben-Oz and Greve (2015) propose that knowledge acquisition and assimilation constitute potential absorptive capacity which enhances strategic flexibility. Alternatively, knowledge transformation and exploitation are realized absorptive capacity with direct influences on performance through fostering process and product innovations. By conceptualizing the four ACAP components in this way, we can see a sequential link between proposed and realized knowledge processes (Zahra & George, 2002). The dimensions are developed so that the occurrence of one is contingent on the other in that potential ACAP capabilities for acquiring external knowledge provides organizations the opportunity to exploit this knowledge. In this sequence, it is expected that potential ACAP (e.g. Acquired knowledge) does not directly translate into performance unless it is realized (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2014). Ultimately, this conceptualization suggests that absorptive capacity is a path-dependent dynamic capability, which enables a firm to obtain new external knowledge. However, once such knowledge is embedded within the firm, additional internal capabilities are required to exploit the knowledge and realize its value (Daspit et al., 2016).

2.1. Research Gaps

As suggested earlier, even though absorptive capacity has been conceptualized as multifaceted, much research treats and operationalizes the construct as unidimensional (Chaudhary & Batra, 2018) or utilizes broad categorizations (Zahra & George, 2002). There is a need to more fully examine the richer and more specific dimensions of ACAP and to analyze their interrelationships as mechanisms for utilizing external advice (Ali & Park, 2016; Flor & Oltra, 2013; Song et al., 2018). Also, while ACAP has been posited to improve organizational performance (Ali & Park, 2016; Flor & Oltra, 2013; Zahra & George, 2002), process-based empirical evidence capturing the four mechanisms of ACAP is lacking.

Our approach follows a more thorough evaluation of ACAP’s impact on SME performance. We address a limitation in previous studies related to the ambiguity surrounding ACAP and its effects on firm outcomes. This perspective adds depth to the understanding of ACAP as a multifaceted construct that influences firm performance. Our study builds upon the insights of other researchers who suggest that the four dimensions of ACAP maintain a dynamic linear path within the learning process (Chryssochoidis et al., 2016; Zahra & George, 2002). This conceptualization emphasizes the sequential nature of ACAP development, where each dimension builds upon the previous one to facilitate knowledge absorption and application.

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Absorptive Capacity: A four-dimensional sequential path

ACAP has been treated both as a dynamic capability that develops when firms acquire, assimilate, and exploit knowledge AND from a knowledge-based perspective as a process for knowledge sharing and transfer (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Maldonado et al., 2018; Matusik & Heeley, 2005; Van Wijk et al., 2008). As discussed above, dynamic capabilities derive from managerial agility to sense environmental opportunities, identify solutions based on external and internal knowledge, reconfigure processes, and redeploy assets (Teece, 2014; Teece et al., 1997). Many organizations, and SMEs in particular, given their resource constraints, may lack capabilities to detect threats or sense opportunities in the external environment and search for corresponding solutions. For instance, SMEs typically depend on owner-managers to provide skills and know-how necessary to navigate their competitive environments. However, owner-managers are often consumed with operational activities and do not have time or other resources to aid them in working on strategic issues (Dyer & Ross, 2008; Santamaría et al., 2009).

Some researchers have argued that capturing the benefits of external knowledge are easier for large firms due to their ability to exploit and leverage more plentiful resources (Loree et al., 2011; Teirlinck & Spithoven, 2013; Tether, 2002). For smaller firms, resources for pursuing and gaining benefits from external knowledge are not as abundant due to their inherent limitations of smallness (Aldrich and Auster, 1986). Therefore, gaining and utilizing external knowledge resides in a more limited set of capabilities.

In fact, as El Hanchi and Kerzazi (2020) point out, smaller firms are similar to startups in terms of their resource limitations and are often dependent on external stakeholders for complementary resources, to help them achieve longer-term growth and performance. Given problems related to small business performance, SMEs and their owner-managers may seek knowledge from external consultants to reconfigure internal processes to assimilate, transform, and exploit any external knowledge gained. Thus, in response to a specific and pertinent external stimulus from a business consultant, SMEs may “possess dynamic capabilities to purposefully create, extend, or modify their resource base” (Helfat et al., 2007, p. 4).

Hence, organizations, despite lacking extensive external sensing and scanning capabilities, may have a dynamic capability that utilizes external knowledge effectively (Koza & Lewin, 1998). We suggest that these can be found in the four ACAP dimensions of acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation (Zahra & George, 2002). This dynamic capability gives an organization the ability to refine, extend and leverage existing competencies or to create new ones by acquiring knowledge from external consulting sources. Additionally, it enables transformation of such knowledge into the business model, thus enabling the organization to respond better to strategic changes.

According to Zahra and George (2002), acquisition and assimilation provide the potential absorptive capacity (PACAP) of the organization, while transformation and exploitation provide the realized absorptive capacity (RACAP) of the organization. Ultimately, PACAP enables the firm to explore new sources of knowledge, while RACAP ensures that new knowledge is exploited for commercial use. Furthermore, this theoretical framework predicts that potential absorptive capacity produces capabilities that in turn are commercialized through realized absorptive capacity. Thus, firm absorptive capacity encompasses path dependent effects in which the first step is supported by potential absorptive capacity, while the knowledge acquired in this first step is put to practical use through application of the realized absorptive capacity (Zahra & George, 2002). Todorova and Durisin (2007, p. 777) state that the recognition dimension of ACAP is the “first building block of the dynamic capability of ACAP,” with empirical evidence suggesting that the three dimensions of ACAP are separate and distinct (Lane et al., 2001). Similarly, Leal-Rodríguez et al. (2014) argue that only when potential ACAP is utilized through realized ACAP do organizations benefit by demonstrating better performance.

This process insight is also found in the innovation literature, which distinguishes between activities that supply knowledge into an organization and activities that exploit this knowledge (Fiol, 1996). Similarly ACAP is suggested to be a process of knowledge sharing and transfer (Matusik & Heeley, 2005; Van Wijk et al., 2008). While other researchers have conceptualized the multidimensional nature of ACAP from a process or path dependency perspective (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008; Maldonado et al., 2018), Volberda, Foss and Lyles (2010) suggest that most empirical research ignores the important process aspect of ACAP dimensions.

As mentioned above, research indicates that of the four constituent ACAP elements, knowledge acquisition and assimilation contribute to PACAP, while transformation and exploitation contribute to RACAP. Scholars have further investigated important aspects of these internal capabilities. For example, in regard to PACAP, knowledge acquisition is served by trust between those involved (Lane et al., 2001), concepts and language with shared meaning (Melkas et al., 2010), and coordinated relationships (Senivongse et al., 2015). Knowledge assimilation involves interpretation of knowledge passed between parties (Sun & Anderson, 2010), socialization (Jansen et al., 2005), managerial support (Lane et al., 2001) and explicit integration and feedback practices (Senivongse et al., 2015).

For capabilities comprising RACAP, transformation includes knowledge sharing, championing and experimentation (Sun & Anderson, 2010). Lastly, exploitation concerns organizational formalization (Jansen et al., 2005) and can be influenced by training (Camisón & Forés, 2011), rewards and allocation of resources (Sun & Anderson, 2010).

Building upon Zahra and George’s (2002) model of the relationship between potential and realized ACAP, we argue that the four constituent capabilities are combinative and build upon each other. We suggest that within potential ACAP, assimilation is supported by acquisition, and within realized ACAP, exploitation is supported by transformation; and that the assimilation to transformation link is the bridge between PACAP and RACAP. Briefly, the logic is as follows. Exploitation of knowledge does not happen on a standalone basis - knowledge must be acquired, assimilated, and transformed to facilitate exploitation. Firms cannot possibly assimilate knowledge without acquiring it, transform knowledge without assimilating it, and exploit knowledge without transforming it.

Specifically, we further contend that each of the capabilities acquisition, assimilation, and transformation is a prerequisite and a motivator for capability development of assimilation, transformation, and exploitation respectively. The need to assimilate (i.e., assimilation capability) is driven by acquisition; the need to transform (transformation capability) is driven by assimilation; and the need to exploit (exploitation capability) is driven by transformation of knowledge. Thus, in the absence of “transformed” knowledge being available, the exploitation capability is unlikely to be developed; and in the event that acquired knowledge is not assimilated, the transformation capability is difficult to develop.

Hence, we posit a logical sequence from knowledge acquisition to its exploitation, with each succeeding ACAP capability being fueled by and enhanced by its predecessor. Conversely, lack of pre-requisite capabilities is likely to hinder the development of successor ACAP capabilities.

H1: Internal processes (capacities) of knowledge Assimilation and Transformation sequentially mediate the path from external knowledge Acquisition to its Exploitation.

Specifically,

H1a: Assimilation mediates the relationship between Acquisition and Transformation.

H1b: Transformation mediates the relationship between Assimilation and Exploitation.

3.2. Absorptive Capacity, Knowledge Exploitation and Firm Performance

Previous research suggests that firms must continuously strive to develop their knowledge bases if they are to prosper and sustain their competitiveness (Griffiths-Hemans & Grover, 2006; Spender, 1996). ACAP has been posited to enhance knowledge transfer and sustain competitive advantage in innovative contexts (Chen et al., 2009). Zahra and George (2002) suggest that ACAP is a dynamic capability which influences the creation of other organization competencies and provides the firm with multiple sources of competitive advantage, thereby improving economic performance. Taken together, the four dimensions of ACAP fulfill necessary and sufficient conditions to improve firm performance. For instance, firms cannot possibly exploit knowledge without acquiring it. Similarly, firms may have capabilities to acquire and assimilate, but not to transform and exploit the knowledge for profit generation.

Despite the importance of acquisition, assimilation, and transformation, knowledge exploitation is expected to be the primary source of performance improvements (Ben-Oz & Greve, 2015; Kogut & Zander, 1992). The resource-based view suggests that it is the exploitation of a firm’s capabilities that contributes to competitive advantage and improved performance (Barney, 1991; Newbert, 2008). The capability to harvest and incorporate external knowledge into operations has long been recognized as an important driver of firms’ performance (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Tsai, 2001) and is especially pertinent in this era of relentless technological development (Thomas & Douglas, 2021). Exploitation enables firms to enhance existing initiatives or develop new ones that build marketing, production, and distribution capabilities, foster product and process innovation, reduce time to market, and increase operational efficiency (Kogut & Zander, 1996; March, 1991; Wilden et al., 2018; Zahra & George, 2002).

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework of hypothesized relationships. The knowledge acquisition, assimilation, and transformation capabilities that constitute the first three legs of ACAP are necessary, but not sufficient prerequisites for knowledge exploitation. Hence, we posit that performance gains are likely only if knowledge acquisition, assimilation, and transformation capabilities result in (or are complemented by) the capability to exploit knowledge.

H2: There is a positive relationship between realized absorptive capacity (exploitation) and firm performance.

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework and hypothesized relationships.

4. Methods

4.1. Sample

Our research questions and corresponding hypotheses involve examining how the potential gains from small business consulting may be realized through the mechanisms of acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation (Zahra & George, 2002). To test our hypotheses, we collected data from owner-managers of small and medium businesses that participated in a university consulting program. Most business assistance programs make extensive efforts regarding the measurement and reporting of performance outcomes for participating businesses. These may include business outcomes such as revenue or profit growth. For example, the Six Steps to Heaven framework to capture program outcomes across entrepreneurship and SME business assistance programs (OECD, 2008; Storey, 2000). In addition, many advisory service programs will gather data regarding a firm’s satisfaction with the program (Storey, 2003). We believe that studying ACAP and performance requires a specific and consistent external learning context to explore the construct and its variations across firms.

During the 2013 to 2018 time-frame, each of these SMEs were provided no-cost management consulting services by a team of one university professor, a SCORE business mentor, an MBA graduate assistant and four to five senior level undergraduate business students. During each year, the consulting program ran two cycles that corresponded with the university’s Fall and Spring semester. Projects lasted three months and typically focused on one or more of the following areas: business expansion into new areas, improving operational efficiencies and improving profits, or developing more effective marketing strategies for revenue growth. Projects could be multi-faceted; in that they might have multiple strategic issues to solve. For example, one local business owner was looking to retire. The project involved developing a strategy to maximize revenues and profits over a two-year period to make the business as attractive as possible to sale. The consulting team analyzed the industry and the firm, developed strategic recommendations, estimated the company’s future value, and provided an implementation process and timeline for the SME owner to reach their retirement goals.

The consulting program’s process consisted of three stages. Stage 1 involved the recruitment and vetting of SME clients for the program. For each cycle, the program recruited regional businesses through online advertising and by directly engaging local Chambers of Commerce, Business Improvement Districts, and start-up incubators. As the program’s capacity for each 3-month cycle was limited to 6-8 projects, the pool of applications was vetted in an attempt to produce an optimal set of projects suitable for teaching research and strategic problem-solving skills. The vetting process was based on the following criteria:

-

Suitability for the program’s 3-month timeline

-

Richness and comprehensiveness of the strategic issues that needed to be addressed

-

Expressed commitment to the project and ongoing engagement

-

Based on grant funding, minority or veteran-owned businesses that met these criteria were given priority.

Stage 2 of the process consisted of executing the consulting engagement for each SME client. Each consulting team followed a general process of activities and deliverables over the three-month timeline. These included:

-

A scope of work for each client containing the project’s problem statement, objectives, research needs, timeline and budgetary requirements. The scope is finalized 2-3 weeks into the project after buy-in from the SME clients, as well as professors and mentors.

-

Industry and firm research involving a range of approaches to data gathering and dependent each project’s specific focus. Methods typically incorporated secondary research from industry and market databases, interviews with owner/managers and industry experts, focus groups with customers, and online surveys to potential customers.

-

Strategic solutions with implementation plans.

-

A final presentation and consulting report of findings/recommendations to the SME owner/managers.

Throughout the process, student teams met each week with professors and mentors. Additionally, each team provided weekly updates to their clients and held client meetings. Early in the process client meetings were extensive as each team developed the scope of work. These become more on an as needed basis, as the project moves into data gathering and recommendation development. The third and final stage of the consulting process involved follow up and assessment of the program’s activities, as well as performance outcomes of SME clients.

4.2. Procedure

To gain a rich knowledge regarding the phenomenon of interest and to ensure the suitability of our theoretical arguments to this context, we first conducted in-depth, relatively structured interviews with a set of five firm owner/managers that participated in the university program. The interviews were designed as a follow-up to their participation. We explored perceptions regarding the support they received from their consulting teams and the quality of the research and recommendations they received. General questions regarding implementation of the recommendations were asked, as well as questions about new ventures, revenue and profit growth, and employment gains.

In addition, we evaluated the suitability of the Jimenez-Barrionuevo, Garcia-Morales, and Molina (2011) ACAP measure we were planning to utilize. First, we needed to determine what/if any terminology needed to be adapted to fit the SME/University Consulting context. For example, Jimenez-Barrionuevo et al. (2011) used the measure to examine learning between two business organizations and is reflected in the wording of their survey questions. Lastly, we used these interviews to explore the suitability of the ACAP measure to our sample and its emphasis on openness to external advice. Overall, we determined that the SME owner/managers interviewed were generally open to external consulting advice which is a theoretically important aspect of ACAP. We also saw variability between our interviewees across the four specific ACAP mechanisms of acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation. These exploratory interviews supported the view that we should pursue more confirmatory research and hypothesis testing.

Once the initial interviews were completed, the main data collection through a large-scale, online survey was conducted. Since each owner-manager provided data for all variables in the survey, we attempted to minimize the possibility of social desirability bias and improve response rate as follows. Respondents were informed that the data and their organizations would remain confidential and that their individual responses would not be identified or analyzed. To improve the response rate, we followed up with a phone-call two weeks after sending out the surveys, clarified questions where necessary, and reiterated the confidentiality provisions. The final response rate was 83%. Since our study utilized a single respondent from each SME, it is susceptible to common method variance (CMV). Hence, we conducted a Harman’s exploratory factor/single factor test, which suggests that if an unrotated solution (with all measurement items included) produces a single factor that accounts for greater than 50% of variance, common method bias is present (Fuller et al., 2016). Test results did not reveal such a factor, allaying CMV concerns. We received valid responses from 99 of the 120 owner-managers we contacted. Owner-managers had an average of 10.2 years of association with their organizations. Sixty organizations had fewer than 10 employees, eighteen had between 10 to 30 employees, another eighteen had between 30 to 50 employees, and three had more than fifty employees. These SMEs belonged to diverse industry sectors including construction, education, energy, engineering, food, fitness, government, healthcare, manufacturing, non-profit, recycling, retail, services, and technology.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Absorptive Capacity (ACAP). We based our measurement of ACAP on a valid and reliable instrument developed by Jimenez-Barrionuevo, Garcia-Morales, and Molina (2011) using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as the basis for our measurement of ACAP. The instrument provides items specific to each of the four phases or dimensions of ACAP i.e., acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation. All items were measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale. Table 1 lists the survey items (questions) corresponding to each phase, which are context-based modifications of the items used by Jimenez-Barrionuevo et al. (2011). The full survey items are described in the appendix.

To ensure we retained only those items which had significant factor loadings, we conducted four factor and two factor CFA. Since these factors are related dimensions of the overarching ABCAP concept, we used an oblique rotation, which allows for inter-factor correlation. We discarded items that did not meet our significance threshold of a loading of 0.3 on any factor (Hair et al., 1998). For retained items, all factor loadings were above 0.4 and all cross loadings were less than 0.3. Table 1 depicts the significant item loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE) for the four-factor analysis.

4.3.2. Performance. We used four survey response items to assess performance. The items were measured on a seven-point Likert-type scale and requested the respondents to rate organization performance following the business consulting project based on sales growth, profit growth, return on investment growth, and profit. Table 2 lists the corresponding survey items. Each of these item loadings exceed 0.9 on a single “performance” factor. The scale reliability coefficient is 0.96.

4.3.3. Control Variables. At the respondent level, we controlled for experience with organization (in years) and designation (ordinally coded 1,2,3,4,5 for Senior Staff, Manager, Senior Manager, Director, and Vice President or above respectively). At the organizational level, we controlled for the number of employees (ordinally coded 1,2,3,4 for less than 10, between 10 to 30, between 30 to 50, and greater than 50 respectively), and industry sector (dummy coded for manufacturing, merchandising, and services).

4.4. Analysis

To test the model corresponding to our hypotheses, we conducted latent variable Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis using STATA software version 15. We used a two-step SEM approach (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). First, we tested the measurement model to validate data to model fit and verify that the indicators reflected their latent variables. In addition to covariance paths between the latent variables, we also allowed error correlations between some items that corresponded to the same latent variable. These items appear close to each other, have similar wording, and carry the same question stem; hence we expect they may carry common variance and correlate (Bollen & Lennox, 1991). These items are Interaction and Friendship; Trust and Respect; Complementarity and Similarity; Similarity and Compatibility 1; Compatibility 1 and Compatibility 2; Documents and Transmission, and Transmission and Time. Second, we tested the structural model to ascertain the relationship between the latent variables and determine if our hypotheses were supported. We included several control variables at the respondent and organizational levels, which may affect the survey items as well as organization performance metrics. Results from our analysis are reported in the section below.

5. Results

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables.

5.1. Measurement model

We assessed overall model fit using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990) and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) (Tucker & Lewis, 1973). The model CFI is 0.93 and the TLI is 0.91 which are above the traditional 0.90 threshold value indicating good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.076, which is below the 0.08 threshold value indicating reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993).

5.2. Structural model

We assessed structural model fit using the same indices as for the measurement model. The CFI, TLI, and RMSEA are 0.92, 0.90, and 0.078, indicating reasonable fit. The structural path results are summarized in Figure 2. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we find that the ACAP dimensions of Assimilation (AS) and Transformation (TR) mediate the relationship between Acquisition (AQ) and Exploitation (EX). For the path AQ→AS, B = 0.79, p < 0.001; for the path AS→TR, B = 0.28, p < 0.01; for the path TR→EX, B = 0.49, p < 0.01. The direct paths AQ→EX, AQ→TR, and AS→EX are not significant. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, we find that the performance effect of realized ACAP is significant. For the path Exploitation to Performance, B = 0.55, p < 0.05. See Figure 2 and Table 3.

5.3. Alternative model test

We also considered a two-dimensional ACAP representation by combining acquisition and assimilation (potential ACAP), and transformation and exploitation (realized ACAP) (Jiménez-Barrionuevo et al., 2011). We identified significant item factor loadings for a two-factor CFA and examined the measurement model and structural model. In both cases, we found that the fit statistics for the two-factor model were weaker than that for the four-factor model.

5.4. Robustness Check

We checked the direct effects of each of the four ACAP components on performance. The relationship between each of the first three components i.e., Acquisition, Assimilation, Transformation and Performance is insignificant. This further strengthens our finding of a linear sequential path wherein knowledge acquisition mediated by knowledge assimilation influences knowledge transformation, whose relationship to performance is mediated by knowledge exploitation.

6. Discussion and Implications

Our research examined the importance of Absorptive Capacity, that is the ability of the firm to obtain new knowledge and apply it in a relevant manner to improve performance, for firms participating in a university small business consulting program. Firms are motivated to improve their performance by allowing consulting teams to work closely with management as they examine firm challenges and develop strategic solutions. Typically, small businesses and their owner/managers are exceedingly busy with the tactical aspects of the business and look to benefit from having their business challenges examined from a strategic perspective. The business consulting context therefore, provides an optimal environment to explore the participating firm’s Absorptive Capacity, as well as their business performance after the business consulting experience.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Noting the extant literature, we utilized a rigorous method for measuring Absorptive Capacity by capturing four dimensions of absorptive capacity including; knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation. We used a two-step structural equation modeling approach to test the hypotheses and assessed the fit of the measurement model as well as the structural model. to A limitation of a number of previous studies where the ambiguities on what ACAP is and a lack of clarity on the effect of ACAP on firm outcomes (Song et al., 2018). Some researchers conceptualize Absorptive Capacity from a broader perspective, while more narrowly examining the concept empirically (Miroshnychenko et al., 2021). Our supposition was that each of the four ACAP dimensions and their inter-relationships were unique and important to examine.

Additionally, in proposing a linear progression of dependency, we followed researchers (Chryssochoidis et al., 2016; Zahra & George, 2002) who indicated that the ACAP components of acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation, maintain a sequential linear path within the learning process. We believe that while these four learning dimensions (capabilities) are present simultaneously in an organization, they must, due to their specific function, build upon and complement each other as part of the process of absorbing external knowledge and making it meaningful to the firm. We examined this linear path and expected that Absorptive Capacity would ultimately influence the business performance of firms who received advice in the program.

Our results indicated that the linear conceptualization of the four dimensions of Absorptive Capacity was supported. We found that knowledge acquisition, mediated through knowledge assimilation, influenced knowledge transformation. Knowledge acquisition as measured by Jimenez-Barrionuevo et al. (2011) emphasizes the importance of social elements of relationships as part of the process of learning from external sources. Social exchange theory suggests that when the benefits of an interpersonal relationship outweigh the costs of the relationship then the relationship is more valuable (Nielsen & Nielsen, 2009; Thibaut & Kelly, 1959). In our research context of business consulting, social exchange when it included trust, friendship, and respect during knowledge acquisition offset the cost of investing time and resources into assimilating and transforming new knowledge. Additionally, we found that knowledge assimilation’s influence on knowledge exploitation, (e.g., tangibly assigning responsibility and applying new knowledge), was mediated through knowledge transformation. These results confirm that each of the unique dimensions of ACAP influence the others in a sequential process.

The importance of this finding cannot be understated. The first and last elements of the ACAP process, knowledge acquisition and exploitation, are easy to identify and understand, whereas knowledge assimilation and transformation have been treated less explicitly and are more opaque. As discussed previously, some research separates Absorptive Capacity into two general categories; knowledge exploration and knowledge exploitation. Many times, assimilation and transformation are described as subordinate aspects of these dimensions, instead of as crucial intermediate dimensions. We maintain that in reality these dimensions do not neatly fit into each of these two orientations and require unique mechanisms to accomplish.

For example, knowledge assimilation reflects how easily knowledge can be embedded into an organization’s existing knowledge base due to similarity with what already exists. Assimilation requires unique effort in evaluating and comparing knowledge as to its correspondence with a firm’s existing knowledge base. If fresh knowledge corresponds to or is similar to prevailing knowledge, then it can be organized into a firm easily. Alternatively, if new knowledge is innovative or drastically different from a firm’s current knowledge base, then more extensive knowledge transformation processes are required.

Knowledge transformation weaves together new knowledge that has been gained and what type of new understanding or approaches are necessary for the organization. Knowledge transformation may require challenges to existing organizational knowledge bases and costs the firm by directing resources into change. If the transformation of knowledge is more challenging, then it may require additional efforts to be embedded within the organization through championing or with proof through experimentation (Sun & Anderson, 2010).

By explicating specifically how each of these mechanisms integrate new knowledge into current knowledge pools, the incremental commitment required by each aspect of the process can be more effectively appreciated. Assimilation is less impactful to the firm as it only requires comparing knowledge. Alternatively, transformation means that the firm is actually beginning to put knowledge into place with new structures and processes. Ultimately these two dimensions are linked together by their function as knowledge integrators and are distinguished by how much change has to occur in the firm to begin to exploit knowledge. Unless new knowledge is assimilated and/or transformed an organization will not be fully able to actualize all of its potential value (O’Leary, 2003). Our study illustrates the value of these dimensions as we see the increasing commitment to each aspect of absorptive capacity required to reach the end goal of acquiring new knowledge in a way that exploits knowledge and captures its value. Our results indicate that interpersonal benefits in knowledge acquisition, the intermediate and incremental processes of evaluating and creating changed processes, are all necessary elements for knowledge to be exploited.

Finally, our study was primarily interested in determining whether a firm’s absorptive capacity was an important element of whether a firm realized value through increased performance from a consulting experience. Our research indicates that small businesses with Absorptive Capacity tend to perform better after their participation in a consulting experience than SMEs that do not have this capability. Specifically, we found that Knowledge Exploitation, measured as the application of knowledge gained from the consulting process as well as the assignment of responsibility for utilizing the knowledge, was related to increased performance. From these results, the ability to take the knowledge gained from the consulting teams and apply them to business challenges was the critical link for whether the business improved. In addition, other elements of ACAP were not directly related to changes in performance, again providing support to the uniqueness of the four dimensions and the importance of their individual roles in acquiring knowledge and capturing value.

6.2. Practical Implications

From these findings we can conclude several practical implications for both consultants and small businesses to make an engagement more effective. Overall, small businesses who possess Absorptive Capacity are more likely to reap performance benefits from business consulting. To achieve these benefits, consultants can engage with their clients by focusing on each of the specific elements of ACAP; knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation. We can elaborate on how this might occur by examining a consulting engagement from a simple 3-stage process perspective. This general process is highlighted in the earlier sample sub-section of the paper. Stage 1 typically consists of a “pre-engagement” vetting process that aids in determining the suitability of a client project for a consulting program. Once SME clients are selected, the second “execution” stage of the process begins as consulting teams develop their project scopes, conduct research and create solutions. This stage concludes when final deliverables are provided to clients. Thirdly, there is typically a “post-engagement” stage which involves follow up with clients and assessment of the effectiveness of the consulting projects.

Each of these stages involve varying activities and complexity, depending on the program and client needs. By integrating the four aspects of ACAP learning process with the three consulting project stages of pre-engagement, execution, and post-engagement, we can more precisely elaborate on key activities and issues that should aid SME absorptive capacity and its influence on performance. See Table 4.

The top row of the table focuses on ACAP knowledge acquisition, which is measured through the degree of trust, interaction, respect, and friendship between the consultant and SME. Therefore, it is important to assess, develop and maintain a social connection throughout the three stages of the consulting process. Pre-engagement activities should be dedicated to assessing an SME’s openness to new connections and ideas, during project execution the consultant and SME should work to develop trust and confidence and finally, the consultant should work to maintain this confidence through support for any implementation of recommendations.

Similarly, the second row of Table 4 suggests specific actions for ACAP assimilation, during each of the three stages of a consulting engagement. We expect that for assimilation, an organizational sensemaking perspective can aid in understanding the application of key activities. Sensemaking describes the process where people perceive and interpret knowledge, important events, and coordinate responses to clarify what they mean (Currie & Brown, 2003; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014). By utilizing a firm’s internal perspective and sensemaking, complexity about the environment or strategic challenges can be reduced during change and can be utilized to derive meaning for decision making (Kumar & Singhal, 2012; Weick, 1993). In applying this perspective, during pre-engagement assimilation it would be important to identify and enlist knowledgeable people from within the organization to discuss the firm and build narrative accounts as consultants work to understand and organize existing knowledge pools (Isabella, 1990; Abolafia, 2010; Weick, 1993). During execution and post-engagement, we can apply Vlaar, Van den Bosch and Volberda (2006) four ‘mechanisms’ that enable sensemaking including – instigating and maintaining interaction, forcing articulation and reflection, reducing errors, biases and inconsistencies and focusing attention. We expect these mechanisms to be particularly effective in terms of understanding existing knowledge and determining what knowledge needs to be transformed which is specified in the third row of Table 4 focuses on ACAP transformation.

Lastly, by engaging key individuals inside the firm, there is likely to be overlap when it comes to the final dimension of ACAP – knowledge exploitation. This will require building consensus and buy-in for taking responsibility in implementing new approaches to organizational challenges. Knowledge exploitation requires key individuals to assume responsibility for applying new knowledge and for identifying key organizational capabilities that are needed to exploit the new information.

7. Limitations and Future Research

While our research aimed at determining the influence of absorptive capacity on consulting outcomes, the study did contain certain limitations. The context of the study were small firms that were engaged with teams of students in a business consulting program. There are many factors that can mitigate the influence or impact any consulting experience, including some related to the firm and the consultants. First, firm owners/managers are under no obligation to actually implement the advice (recommendations). As the consulting services were offered free as a condition of an external grant that partially funded the university consulting program, there could be reduced incentive for the owner/managers to “get their money’s worth” by implementing the recommendations.

Follow up research suggests that many firms, while agreeing with the advice that is given, never follow through with strategic recommendations. This lack of implementation can be related to time pressures, lack of resources, or ultimately the failure of the business. In addition, the sophistication and fluency of the consultants and the quality of consulting may play a role in determining the impact of the experience. The findings of this study must be considered with these factors in mind.

In addition, our study relied on single respondents during the interview and survey process. Owners typically in small businesses are the dominant influence (Dyer & Ross, 2008) and many times the only management level perspective due to the size of the staff. Therefore, the research was developed from the critical knowledge-base of the business. Further, our study may contain non-response bias as some firms that completed the consulting process were no longer in business during the follow up period and were not available to participate in requested interviews or surveys. Lastly, we note that performance was assessed by respondents following the consulting intervention and relative to the previous year (e.g., sales growth year over year). Despite temporal precedence, significant pathway correlations, and controlling for other sources of performance we should be careful with the implication of causality. A strong claim to causality would require a longitudinal study with specific and data driven performance observations before and after the consulting intervention.

Learning in organizations continues to be an important topic for strategy and small business researchers. From our research on small businesses and their desire to learn from external sources, we determined that trust and the value the firm places on the sources of new knowledge. Knowledge transfer and the role of trust has been extensively studied in the strategic alliance, joint venture literature (e.g., Li et al., 2014) and could aid future research in the SME learning context as well. Future research could focus on the development of Absorptive Capacity in organizations. For small organizations, learning and absorbing information necessary to improve performance is necessarily vested in key individuals. Determining how to assess multiple individuals and their roles in learning for small firms should be elaborated on.

We provide the following three specific suggestions for future research. The first entails conducting a longitudinal study to capture performance before and after consulting intervention and/or comparing with a matched “control” group of small businesses, who haven’t received the consulting intervention. This could provide stronger causal mechanisms on the link between consulting interventions and firm performance (Kostopoulos et al., 2011). The second involves ascertaining how (apart from the CEO), other personnel (roles) in a small business impact external knowledge absorption and implementation of recommendations (Von Briel et al., 2019). This may be accomplished through qualitative interviews with CEO and others to corroborate the mechanism (sequence) from Acquisition→ Assimilation→ Transformation→ Exploitation, and to identify barriers to/drivers of engagement/implementation of recommendations. The third suggestion is about studying other areas beyond conventional financial performance that ACAP could impact, in the context of a small business following an external knowledge intervention. These include innovation (e.g., new product/service development) using measures such as percentage of revenues from new products/services and operational efficiency (e.g., process improvements to reduce costs and/or improve quality) using measures such as factor productivity and defect rates (Aliasghar et al., 2023; Moilanen et al., 2014).

Ultimately this paper is an important contribution, in terms of small business management research and organizational learning. The paper confirms the importance of external sources of knowledge, specifically consulting, for improving small business performance. The research investigated the Absorptive Capacity and its influence. In addition, by examining four specific dimensions of ACAP, we presented a more fine-grained investigation of the concept and tested the interrelationship between these dimensions providing support for the linear relationship between them and firm performance. The study suggests that while all four mechanisms of ACAP are interrelated, eventually knowledge exploitation through assigning resources, developing specific responsibilities for solving business challenges is the key for business improvements.