Introduction

The livelihood of majority of the world’s population is based on micro and small-scale enterprises (MSEs). These enterprises are, in the forms of formal and informal, adopted by majority of the people for their livelihoods or household economies. The number of MSEs is more in least developed and developing countries than in the developed countries. In developing countries in Asia and the Pacific, MSMEs constitutes more than 90% of all enterprises, provides over 60% of jobs in the private sector, generates 30–40% of total employment, and contributes nearly 30% to total direct exports (UNESCAP, 2011). Therefore, MSEs are major sources of income for both rural and urban areas in developing countries (Lamsal et al., 2017). These enterprises are small in terms of the sizes of investment, production and the number of workers that they employ. The definition and scope of micro and small enterprises may vary in different countries. Nonetheless, MSEs have been recognized worldwide, for their significance in utilizing the local resources, creation of local employment, discovery, and promotion of cultural innovations (Shrestha, 2015). Therefore, the MSEs contribute to improve the households’ economic prosperity and the national economy (Raposo & Paco, 2011). Moreover, the MSEs have been acknowledged as a means of poverty reduction in developing countries (DCs) and in least developed countries (LDCs). Therefore, Governments and non-government agencies are promoting MSEs as one of the means of poverty reduction through creating income-generating activities and employment. In fact, in the last few decades, many of the countries have been implementing the promotional activities and financing for the development of MSEs (Ayalu et al., 2022).

The development of large-scale industries is controversial in LDCs including Nepal, due to multiple constraints i.e., the smaller domestic markets, low income and other complications in the infrastructure and the facilities of product selling (Dhungana, 2009). It is also imperative that the low contribution of large-scale-industries to the household economy in the LDCs like Nepal, inevitably impacts the living standards of the people and therefore their living standards may also be defined as under-developed (Adhikari, 2018; Khatri, 2018). Therefore, governments in LDCs and other developing countries have increasingly focused on prioritizing the development of MSEs (UNCTAD, 2005), with the view to contributing to the country’s economy.

In fact, when we look at promoting the function of MSEs within emergent economies, many issues were identified by various scholars (Ayalu et al., 2022). The researchers of this study, therefore seek to resolve these issues by identifying effective solutions through the sociological perspective, for emergent economies, such as Nepal. From the very outset, Thornton, Ribeiro-Soriano and Urbano (2011) utilized the concept of institutional logics, and stated that socio-cultural factors play an important role in the creation and development of entrepreneurship. The factors such as imagination and creation within the social context, enhance the ability to actually create within a social context (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). Nonetheless, much of the research to date has tended to typically focus on the economic approach of entrepreneurship and consider traditional business theories (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004; Wennekers et al., 2005). “In spite of this growth in the literature and the salience of entrepreneurship in public policy, the influence of social and cultural factors on enterprise development remains understudied” (Thornton et al., 2011, p. 106). Therefore, the researchers within this study found an absence of the application of sociological theories within entrepreneurship research and thus attempted to explore the issues that MSEs’ face as they engage in the journey of ‘becoming’ through a sociological perspective i.e., Bourdieu’s ‘habitus’.

The aim of this study is to explore the sources of becoming for the entrepreneurs and ways of acquiring the entrepreneurial knowledge and skills in the context of Nepali MSEs. The sources and ways of the entrepreneurships of MSEs will be analyzed based on the experiences of the entrepreneurs on being motivated to their entrepreneurship and ways of acquiring the entrepreneurship-knowledge during their life.

Literature Review

Definition of Micro, Cottage and Small Enterprise

Micro and small enterprises are categorized based on the size of their business. However, the nature and operating methods of the business are also contextually unique. Nonetheless, cottage enterprises are also included in these categories, which define entrepreneurs with micro or small amounts of capital (Karki, 2013). Interestingly, the business interventions of these enterprises are also in small sizes in the markets. Although different countries and scholars have defined micro and small enterprises in different ways. However, what is common across the scholarly literature is that the category or scale or type of enterprises is defined based on the volume of capital, or the coverage of the markets.

In Nepal, the government has defined about the types of the enterprises/industries based on the sizes of capital and other capacities. According to the Industrial Enterprise Act, 2020, micro and small enterprises have been defined based on the investment amount and use of other resources. Therefore, microenterprises constitute up to two million Nepali rupees of fixed capital, excluding land and other property. The entrepreneur would be involved in the operation and management of the industry and employ up to nine workers including him/herself. The “technology should have a capacity of a maximum of 20 KW and excludes industries of tobacco and alcohol. The cottage industries use the electric energy up to 50 KW to operate machine and tools. Likewise, a small-scale enterprise utilizes the fixed capital up to 150 million Nepali rupees” (GoN, 2020). Therefore, micro and small-scale enterprises constitute the small amount of investment and resources and contribute individually a small share to the national economy.

Micro and Small Enterprises in Global Context

Micro and small enterprises (MSEs) have now become essential worldwide, especially as they contribute to poverty reduction through employment creation, based on local resources and small-scale investments (Akugri et al., 2015). According to the IFC, almost a decade ago, there were around 125 million formally registered as micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) across 132 countries, where 89 million MSMEs are functional in developing economies (Kushnir et al., 2010). Within Nepal specifically, MSMEs are popular and suitable among the small capital population (UNESCAP, 2020). In fact, the creation and operation of small businesses continues to grow. Interestingly, a large number of MSEs are family businesses without registering with the concerned government authorities (Ghimire, 2011). Nonetheless, it is important to note that whether operating formally or informally, these businesses have contributed to household economies. OECD (2018) stated that the majority (70 - 95 percent) of these firms are microenterprises, with less than ten employees, and most of these firms tend to only have the owner/manager working or leading the business. Most of the world’s populations are engaged in MSEs and have adopted them as a main source of income, which has been contributing to the livelihood of the households (UNESCAP, 2020).

McPherson (1996) highlighted that the economists appeared to neglect small enterprises during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, due to the preoccupation with investing in large-scale industries during the European industrial revolution. In fact, European countries were focusing on large-scale and capital-intensive investments. Consequently, lesser developed countries such as Nepal, could not focus on developing their own national economy, due to the lack of capital and technologies. However, “since the 1970s, this trend has reversed itself as an ever-growing number of researchers, policymakers, and members of the assistance community have begun to examine the possibilities” (McPherson, 1996, p. 254). Therefore, MSEs clearly offer significant potential to contribute to household economies within emergent economies.

Micro and Small Enterprises in Nepal

In Nepal, MSEs are largely based on the local resources and traditional skills but very little use of modern technology. Pandey (2004) stated, the MSEs have been more focused on the manufacturing of food items such as rice, pulses, oil, fruit items, vegetable production and processing, candy, dairy items and other similar food items. He further stated, other areas that MSEs’ may be involved in, include forest fiber-based industries, wooden and metal handicrafts, handmade paper and products, apparels, garments, woolen carpets, pashmina shawls and rugs and leather. There is also a focus on metal and plastic household utensils, wooden, plastic and metal furniture, printing press, polythene pipes, utensils, jute products, poultry products, livestock products, wire drawing, nail and iron rod, sheet metal, gig and black pipes, rubber tires and tubes, plywood and boards, color paint products and zinc oxide are other sectors where SME engagement is high (Pandey, 2004, p. 8).

Interestingly, the majority of the rural population of Nepal are engaged in agricultural or related activities (Anriquez & Stloukal, 2008), The rural people are engaged either as laborers or small-scale farmers for their livelihoods. Nonetheless, “although the definitions vary according to the country-context, it is generally agreed that the informal sector, whether rural or urban, comprises micro and small-scale enterprises producing and distributing goods and services in unregulated but competitive markets” (Harvie, 2003, p. 2). Nepali people are engaged in those enterprises, and understand that those enterprises are one of the primary sources of income for their livelihoods. The enterprise sector in Nepal has a dual structure (Kharel & Dahal, 2020). On the one side, there are big industries with modern concepts and technologies, capital-intensive, resource-based, and import-dependent (UNCTAD, 2005). The number of large industries is very low in Nepal. On the other hand, the MSEs are operating with the capital and production capacity at micro/small scales, they are more labor-intensive, and largely based in the local markets (Ghimire, 2011).

The MSEs are producing the goods and services based on local skills, resources, and technologies. The MSEs based on modern technologies are also operating. On the other hand, the market has been extended worldwide through various technological platforms and entrepreneurs can now deal with individuals widely, as per the capacity of their enterprises (Rai, 2018). However, the products of brands such as, Apple, Samsung, Dell, Unilever, Adidas, and other multinational companies spread over the broader area of the markets and deal with the mass volume of production as they have access to modern and sophisticated technologies (Jobber & Ellis-Chadwick, 2012). Another reality within the lesser developed and emergent economies is that the small enterprises of natural fiber, clothes, metalcrafts, and other enterprises of local products have also been running for a long time based on the local needs and demands (Panthi, 2015). Thus, the MSEs have been operating under the duality of localization and globalization.

The research questions posed within this study, focus on interpreting the contextual sources, the ways of entrepreneurial orientation and the dispositions valued by entrepreneurs within less developed economies, such as Nepal. In fact, “habitus functions as structured and structuring dispositions” (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 52). Habitus is also an ongoing process of building and rebuilding the social embodiments (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Therefore, the participants’ lived experiences within this paper demonstrate the sources and ways of their habitus, therefore exhibiting the field.

Course of Becoming: Habitus

The notion of becoming refers to the process of ‘world-making’ or shaping and instituting the habitus (Reay, 2004). The social world, in particular, is not ‘ready-made’; but it is the material effect of an ongoing enactive process of ‘world-making’ (Goodman, 1978). It is a process of instituting the perceptions, emerging thoughts, and being motivated, knowledgeable, and skilled for maintaining obedience to the culture (Bourdieu, 1990). Within the context of this study, we consider the course of becoming as being motivated and knowledgeable enough to initiate and operate a particular type of enterprise within an emergent economy. The process of becoming is, of course, always ongoing and progressive so that new inventions and innovative ideas are always possible.

In fact, we could say that it is very much about the process of the coming-into-being of the world (Ingold, 2000). The individuals live with the endless process of accumulating the culturally acquired tendencies and predispositions for ensuring the existence in a certain interval of time-space (Nayak & Chia, 2011). Therefore, it is a process of the embodiment of knowledge and skills within individuals, that enables them to exhibit the strategies and activities that they have accumulated, into the social field. Hence, sociologically, it is an ongoing process of building and rebuilding habitus.

Another perspective of institutional logic is also popular in the field of business and organizational development. Institutional logic provides a cognitive map to give meaning to social reality and stipulate legitimate means and ends, each logic also defines the value of the outcomes of social activity (Thornton et al., 2012). The concept of institutional logics believes that ‘each field has a logic’. The perspective of institutional logics views that the actors as culturally competent and equipped with the knowledge and skills to recognize institutional regularities and differences, and consciously consider and deploy them (Perkmann et al., 2022, p. 5). The logics are the roots of building habitus and the actors are always guided by the logics.

Bourdieu (1977), introduced the sociological theory known as the “theory of practice” and highlighted three fundamental concepts i.e., habitus, field, and capital as the components of social practice (Wallace & Wolf, 2008). Habitus is an ongoing process of becoming, testing in the field, and also updating the behaviors appropriate to the field (Bourdieu, 1977). The habitus contains the embodied dispositions guided or deposited by the historical learnings, thoughts, and that exhibits in the way of life (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). It entails the cognitive and somatic structures; actors use to make sense of and enact their positions in the field (De Clercq & Voronov, 2009).

To make habitus conceptually clear, one can take a question asked by Bourdieu, “how can behavior be regulated without being the product of obedience to rules?” (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 65). The culture discloses the patterns of confirming behavior to the individuals or group/s of individuals. The persons unconsciously adopt the social patterns and norms that surround them through the experiences of their everyday life and formative experiences in the early years. The notion of ‘right’ and ‘appropriate’ becomes an ingrained instinctive pattern of thought and behavior. Bourdieu (1990) refers to these instinctive tendencies towards certain behaviors as habitus (Beames & Telford, 2013). The notion of ‘right’ and ‘appropriate’ is the foundation of creating values and dispositions that shape instinctive patterns of thought and behaviors.

The values and dispositions shape the way of living of an individual, group, or larger space. Each of the people cultivates his/her instinctive values and dispositions. Another condition may appear that the groups from the same and similar social environments share a similar group habitus. That condition is named ‘doxa’ by Bourdieu, which is a foundational and unconsidered cultural belief (Beames & Telford, 2013). Doxa not only encourages the acceptance of things as they are, but also gives us a sense, that the way things are in the way they ought to be (Jenkins, 2002). Thus, individuals or groups exhibit their habitus in every aspect of their lives.

As a reflection of habitus, they exhibit particular ways of thinking, expectations, choices, politics, religion, speech, posture, a way of dressing, and the relevant responses within their industries (Beames & Telford, 2013). The habitus also refers to the way of thinking and the way of doing, in particular social contexts. The way of thinking is driven by certain values and beliefs or maybe referred to as ‘common sense’ (Bourdieu, 1986). Habitus is also the process of self-legitimation influenced by the formative experiences of early life. The changing or evolving social context may produce an uncommon situation for a particular habitus (Jenkins, 2002). Living in the same geographical location for a long duration, familial structure, and the social surroundings provide the durable, instinctive dispositions that form habitus (Bourdieu, 1977). Thus, the habitus refers to the instinctive dispositions unconsciously collected from social living and exhibition to society.

In fact, social actors follow a particular ‘way of life’ reflecting a cumulative expression of their early social experiences (Jenkins, 2002). However, Bourdieu described ‘habitus’ as a person’s cumulative expression of the dispositions earned from society (Bourdieu, 2005). It is structured by the experiences in the social life of the person it belongs to, and the habitus structures the field in which the person moves (Bourdieu, 1984). It is the process of becoming. Therefore, this research study seeks to contribute to current scholarly literature by exploring the sources and ways of building habitus for MSEs within the context of Nepal.

Source of Entrepreneurial Becoming

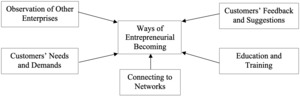

Based on the sources of motivation, the scholars have divided entrepreneurship into three types such as opportunity entrepreneurship, necessity entrepreneurship, and opportunity and necessity hybrid entrepreneurship (Caliendo & Kritikos, 2019; Kallner & Nystrom, 2018; Van Stel et al., 2023). They have evaluated the performances of those enterprises in different ways and concluded different types of entrepreneurships contribute differently to economies and societies (Van Stel et al., 2023). However, entrepreneurship is a practice of economic activities in the social world, in line with ‘economic reason’ (Bourdieu, 2005). But not all people become entrepreneurs due to economic needs and are involved in other types of professions. Bourdieu (2005) further stated that the economic reasons immediately correlate and connect with social reasons automatically. Each of the social activities has either single or multiple reasons from the creation, growth, continuation, and other forms of dynamism. This article has tried to find out how the mindset of entrepreneurs is prepared to do business. What are its sources of entrepreneurship mindset in Nepali context? The perception of an individual is configured through family, education, and work experiences, which influence the perceptions and expectations of the individual’s intention toward entrepreneurial behavior (Kautonen et al., 2011). Thus, several factors might play a vital role to determine the individual’s career including the intention of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial habitus. Jackson (2016) has explored the career narratives of the Black family business and concluded that the family career legacy affects the individual’s thoughts and actions. Children can follow their parent’s professions. Parents are early role models for children in acquiring social values, habits, and attitudes and can act as negative or positive models for entrepreneurship (Morales-Alonso et al., 2016; Pablo-Lerchundi et al., 2015). There is a statement in Nepali society that “the farmer’s children can be the farmer”. But now, because of the modern education system, farmers’ children have started to take up other professions because they have become able to choose the professions of their interest. But in South Asian countries including Nepal, huge number of people are adopting parent’s profession. This is the effect of parental role models (Bosma et al., 2009).

Yan, Huang and Xiao (2023) have also documented how education also plays an important role in the development of entrepreneurial mentality. Education provides literacy, a broader view of society, life skills, and basic knowledge for professions or businesses to the individuals. Entrepreneurship education has been taken as one of the main areas in the education program and a large number of educational institutions – schools, universities, and training institutions - have been providing entrepreneurship education. Pallas (2000) has concluded that there are associations between schooling and labor-force participation, career transitions, occupational status, and wealth. Entrepreneurs put great value on education. Education provides literacy and knowledge for searching for better opportunities in the business field and compares the data among many enterprises.

In the field of entrepreneurship, work experience also plays a vital role in motivating one to be an entrepreneur and learn to be successful in entrepreneurial life. It is also known as the ‘previous experience’ that would eventually shape the strategies and tactics of the entrepreneurs, organizing them according to a relational logic (Bourdieu, 1990). The cognitive structure accumulated from these past experiences guides people in recognizing an entrepreneurial opportunity (Baeta & Andreassi, 2021). Scholars have argued that one would value previous experiences as one of the sources of entrepreneurial motivation and building up the entrepreneurial career.

The literature has highlighted the importance of a ‘role model’ in entrepreneurship development. The behavior of entrepreneurs does not only depend on their characteristics, it is important to note that the environment also plays a vital role (Shane et al., 2003) because people learn to live from the environment. Dohse and Walter (2012) have highlighted the role of a ‘role model’ to motivate and transfer knowledge and skills to another person who wants to be an entrepreneur. The role models can influence both the outcome expectancy and self-efficacy of the individual, which can encourage following a career of being an entrepreneur (Lent et al., 1994; Nauta et al., 1998).

However, we found the gap in literature on entrepreneurial becoming in the context of emerging economies like Nepal regarding the MSEs. Therefore, we contribute a literature on the sources of entrepreneurial becoming of MSEs in LDCs through analyzing the experiences of entrepreneurs who have been doing business for many years. The study investigates the sources of entrepreneurial becoming that we can add in the existing literature.

Ways of Entrepreneurial Becoming

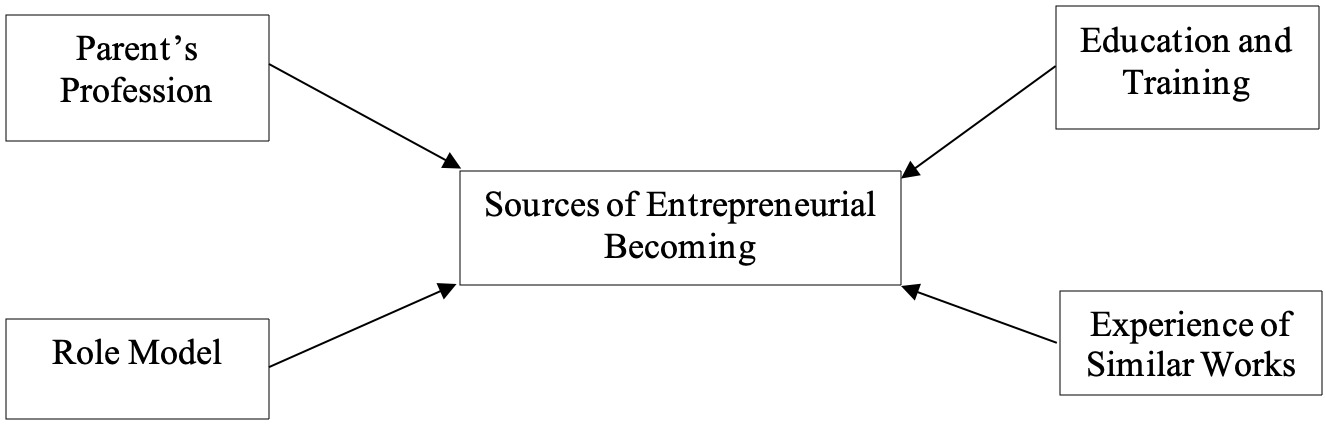

Doing enterprise is also like a social game. There is always competition among entrepreneurs of similar businesses or others. Entrepreneurs usually learn everything from other people’s activities and do their own business. The process of learning and exploring new or appropriate knowledge and skills is continuous in entrepreneurship (Cowdean et al., 2019). Therefore, entrepreneurship is a process of learning from different sources and working for business success. Politis (2005) stated, “entrepreneurial learning is often described as a continuous process that facilitates the development of necessary knowledge for being effective in starting up and managing new ventures” (p. 401). Abbasianchavari and Moritz (2021) have carried out a study regarding the causes of initiating enterprise. The entrepreneurs answered that ‘others’ significantly influenced their decision. They indicated ‘others’ as the other entrepreneurs of different businesses.

Educational learning and training are identified by Bourdieu (1986) as the source of intellectual qualification and human capital (Walter, 2014). People with an entrepreneurial mindset want to get an education or training in the field of enterprise and learn the related knowledge and skills. Shrestha (2015) has also stated, academic education and non-academic training programs as a useful resource for the entrepreneurship (p. 23). Therefore, the entrepreneurs learn business knowledge and skills even through the programmes of education and training. The marketing concept of business focuses on the needs of the people that create the opportunity of entrepreneurship. In the business language, the people who buy the goods or services called customers. The marketing concept says that an organization’s purpose is to discover needs and wants within its target markets and to satisfy those needs more effectively and efficiently than competitors (Slater & Narver, 1998). The ultimate goal of business is to earn more money through maximizing the customers’ satisfaction. If the number of satisfied customers increases, the business will flourish. Therefore, “the business companies focus on their most demanding customers and attempt to innovate to solve their problems thereby creating a product or service which is likely to add value to the vast majority of customers with less stringent requirements” (Lawson & Samson, 2001, p. 392).

Sullivan and Marvel (2011) have carried out a study on the network of entrepreneurship and concluded that those entrepreneurs with a greater number of network ties appear better positioned to obtain knowledge advantages. Business networks help entrepreneurs to learn and transfer business knowledge and strategies among themselves. Gilmore A. (2011) stated, social networks contribute something to the entrepreneur, either passively, reactively or proactively whether specifically elicited or not. The network is a socially constructed ‘strategic alliance’ for instituting change, developing growth, and creating the future (Anderson et al., 2010). Zhou, et al. (2023) concluded that “When corporations are embedded in local networks, frequent interactions among local networks make resources homogeneous, increase corporations’ reciprocal capital” (p. 1125). The previous research suggests that one of the benefits of a collaborative network orientation is that it promotes a wider and larger range of network ties, which in turn reduces potential cost dependencies by enhancing resource options (Sorenson et al., 2008).

During the literature review, it was not found that there has been an in-depth study of how MSEs learn to do business. There was no evidence-based answer to the question of what are the ways that entrepreneurs learn to develop enterprises. Therefore, the study contributes the literature regarding the ways of entrepreneurial becoming in the context of MSEs.

Research Questions

The purpose of this inquiry was to explore the state of ‘habitus’ from the experiences of the entrepreneurs of MSEs. The first component was to explore the sources of ‘becoming’. The second component was to explore the ways of ‘becoming’. In line with the purpose of the study, the following research questions were developed:

-

What are the sources that contribute to ‘becoming’ for MSEs?

-

How do MSEs acquire business knowledge and skills?

Methodology

I followed ‘interpretivism’, a social approach to see the world. Interpretivism believes in the multiple realities ‘due to the fact of pluralization of the lifeworld’ (Flick, 2006) for looking at the contextual depth (Kelliher, 2005). Interpretivist perspective goes beyond the empirical truth and logical proofs. According to this perspective, the worldview of contextualism builds on the concern for the human condition that best expresses “I mean more than I say” (Kramp, 2004). Narrative inquiry was deemed as being appropriate, because it has been defined as a research approach that begins and ends in the storied lives of the people involved (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). The researchers have accepted narrative inquiry as a popular means of organizing and articulating the experiences. Narrative inquiry considers story/ies as the main source of data and basic unit of analysis (Kramp, 2004). With this in mind, the stories of entrepreneurs have been collected for this study.

Six entrepreneurs have been involved in this study based on the principle of purposive sampling. It is more complicated than asking questions expecting the exact number of participants for the research design of narrative inquiry by the practice that depends on the decision of researcher/s as they feel the requirement of enough information to the research questions (Lal et al., 2012). Moreover, the actual number of participants used in a study does not necessarily translate to the quality of insights. The qualitative approach employs the purposeful selection of the information-rich cases which is oriented toward the development of idiographic knowledge from individual cases (Goulding, 2005). Therefore, we followed a way of purposive selection where participants were selected only if they have lived-experience on the entrepreneurship considering them “information-rich” (Patton, 2002).

They (research participants) claimed themselves as being successful entrepreneurs in their business, they may also have experienced business failure at some point in their entrepreneurial journey. It is also important to note that both male and female entrepreneurs, from urban cities and rural villages were involved collecting the experiences and practices of different environments which provide a comparative and comprehensive understanding of the issues. The researchers involved the entrepreneurs of different products such as metalcrafts, cloth handicrafts, natural fiber fabric, leather footwear, fruit juice and cereal seeds.

Data Collection, Analysis and Interpretation

The researchers were engaged to search about the experiences of the entrepreneurs of MSEs in Nepal. They reached to six entrepreneurs of MSEs of different types and locations within the country. The narrative data were collected from the entrepreneurs through the interviews in several rounds. The interviews were concentrated on collecting their story and experiences of entrepreneurial becoming in their life. The data collected during the research is presented and analyzed as follows:

Sources of Becoming

When the researchers talked with the entrepreneurs of MSEs on how they started their enterprises of their choice. The participants told the story of how they became entrepreneurs. Gopal, an entrepreneur of fruit juice and cereal seeds, stated:

I was born in a farmer’s family and got engaged in farming. I had already known the potentiality of agriculture enterprise. Up to now, I have been continuing the farming of paddy, corn, potato, and other vegetables. Thus, I have started the enterprise based on agricultural products and the materials locally available (Gopal, Transcript, 22 March 2021).

Gopal’s experience showed that the orientation received from his family profession. The parent’s occupation inspired him to become an entrepreneur of agricultural products. Another story of Madan was also the same of becoming an entrepreneur of leather footwear. He was from the family of ‘Sarki’ (Cobbler) which was a social caste in Nepal with the profession of leather works (in Nepal, social caste is an identifier of profession). Madan detailed the origins of his business:

We started the business of leather footwear in Banepa, a small city of Nepal, from 2007 AD. It was my family profession continued my parents and grandparents" (Madan, Transcript, 13 March 2021).

Evidently, Madan followed his family profession, but he evolved the family profession by turning it into an enterprise of leather footwear, and formalizing it in a market area, which helped him to move to the professional mode of business.

Another participant of the research was Shila. She was also an entrepreneur of natural fiber fabric, born in the ‘Damai’ (Tailor) family, a social caste of sewing clothes in Nepal. Shila had the skill of sewing clothes from her childhood because she learned about this skill from her parents. She expressed:

I was familiar on cutting and sewing clothes and motivated to do better than this. I had a dream of creating a business of cloth making in a professional way. Thus, I started this business of natural fiber fabric before 18 years" (Shila, Transcript, 2 April 2021).

It is evident from all three informants, that their professions were dictated by their ancestors and previous generations. Gopal, one of the research participants, was motivated, and became an entrepreneur by his parent’s profession of farming. Likewise, Madan followed his family profession of leather footwear. Gopal and Madan both were continuing their enterprises in their villages. Shila was inspired by her parent’s profession to start a tailoring business. Gradually, she initiated the enterprise of natural fiber fabric.

The entrepreneurs expressed their desires for education and elaborated on the significance of entrepreneurial education. Roshani emphasized the importance of education and trainings for being an entrepreneur. She added:

I have completed a Master’s degree. Being educated, I am able to understand all legal provisions, business information, and receive the facilities provided by the government in the sector of enterprise development. I started my business after the basic skill training for three months (Roshani, Transcript, 21 March 2021).

It is evident that Roshani feels that the educational qualification she has acquired has helped her to become an entrepreneur and run it well. She knows about the legal provisions, business skills, and the facilities provided by the government because of her education. Roshani unpacked her experience of starting the enterprise only after participating in the basic skill-training for three months. She received the fundamental skills of the handicrafts, especially the weaving of woolen items. The training influenced her to initiate the enterprise and enforced her to search for the knowledge and skills relating to the enterprising activities.

Santosh, an entrepreneur of natural fiber fabric, expressed:

My family was from agricultural profession. My parents were encouraging me to search for a government job. I got an opportunity to participate in a training of natural fiber processing. Then, I started to do this business (Santosh, Transcript, 16 April 2021).

Santosh provided a narrative about the experience of when he initiated his enterprise. He started the enterprise of natural fiber which was against his family profession. He was oriented and inspired from skill-training of CSIDB and job experience in a similar field. He became inspired to establish the enterprise of natural fiber fabric, because of the knowledge acquired through the training and the experience of working in the similar business of natural fiber.

Another research participant, Binod had also initiated the business of metalcrafts from the experiences gained during the job of a similar enterprise. He explained his story:

When I was working as an accountant in an enterprise of metalcraft, I knew about all of the raw materials, sources and locations. I learned about the sources of materials, quality of the brass and copper sheets and usage of these materials. I was familiar with the skilled workers of this enterprise during my job. I knew about the types and availability of skilled workers. Then, I started the business of metalcraft in Kathmandu (Binod, Transcript, 27 February 2021).

It is evident that Binod was inspired when he was exposed to the field of metalcrafts. Despite being an accountant, he decided to start the enterprise of metalcrafts because of the entrepreneurial skills that he had developed.

Roshani, an entrepreneur of cloth handicrafts, was inspired by other entrepreneurs and this in turn motivated her to start her entrepreneurial venture. She expressed her story of business:

I was inspired by the success of Ms. Mausami Upadhyaya in the business of cloth handicrafts. She motivated me to be an entrepreneur and got affiliated with the networks of entrepreneurs so that it would be easy to be a successful entrepreneur (Roshani, Transcript, 21 March 2021).

From Roshani’s anecdotes, the inspiration for being an entrepreneur comes from reading, listening or looking at the recognized personalities of others. She saw the successful personality of Ms. Mausami Upadhyaya and was impressed by her thoughts and entrepreneurial ventures, which resulted in her becoming a successful handicraft entrepreneur. It was evident that that other entrepreneurs motivated her and were the inspiration in her journey of enterprise. She also noticed the local opportunities within the handicraft industry.

Ways of Becoming

The researchers searched for the ways of entrepreneurial becoming from the experiences of the research participants. Gopal expressed his experience of collecting business knowledge. He stated,

In previous days, I visited the markets of Banepa, Dhulikhel, Kathmandu, and villages near to my enterprise for collecting the fruits and different seeds of grains. Now, this is not the age of marketing by visiting door to door. We have to use mobile phones, Facebook, and the internet. If we use these facilities, we can reach easily to more customers (Gopal, Transcript, 11 February 2021).

Gopal had observed the business activities of other entrepreneurs. He gained many ideas of designs, production processes and selling the products from the practices of other entrepreneurs. Therefore, he valued “learning by observing others’ practices” as a way of acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge and skills.

Another entrepreneur, Santosh, has similar experience of continuous observation of others’ practices. He stated,

I visit regularly to other enterprises and their retail shops. I also participate to the business fairs. I collect the techniques from the observations and business workshops (Santosh, Transcript, 16 February 2021).

He highlighted the importance and utility of the observation of others’ practices in the entrepreneurship career as an inseparable action to be continued for the success of the business. Learning from other entrepreneurs is a reality and a never-ending process in the life of human beings. Likewise, Binod gave priority to observing the products of other entrepreneurs and their business activities. He expressed,

I always see the products of others when I am in the market. I compare these products with mine. I go to other’s factories, interact about the manufacturing issues, collect new ideas, and share them as needed (Binod, Transcript, 27 February 2021).

Binod also valued the idea of observing others’ practices to learn more ideas of business.

Gopal values the experience of participating in the business fairs. In this regard, he shared,

I participate to the business exhibitions of different places of Nepal. I sell my products, observe others’ products and creative ideas as well. My main objective of participation is to observe the products of various entrepreneurs and collect new knowledge and ideas for the enterprise and know the customers (Gopal, Transcript, 30 September 2021).

Gopal highlighted the importance of business exhibitions for observing and learning new things and does not miss to participate in those events. In reality, these business exhibitions seem like a platform of learning which contributes to shaping the habitus of the entrepreneurs which will affect durably to their business.

Madan added to his storylines regarding the collection and implementation of the customers’ feedback and suggestions. He recalled,

Obviously, customers always teach us about making better and suitable products. We have been learning about the quality, permanence and the complaints from the customers. We get the chance of improving our products from the feedback and suggestions of the customers (Madan, Transcript, 16 August 2021).

Madan had a practice of collecting feedback and suggestions from the customers and implementing them to their process of product-making. They gave enough proof of taking the ‘listening to the customers’ as one of the major ways of acquiring entrepreneurial ideas and skills.

Likewise, Roshani had similar experience of respecting the customers’ feedback. She expressed, “As per the suggestions and feedback of customers, we make quality products” (Roshani, Transcript, 18 June 2021). Another entrepreneur, Shila, stated, “The wholesalers and retailers have been giving the ideas of producing new designs and quality” (Shila, Transcript, 3 July 2021). From the experiences of the entrepreneurs, listening and following the feedback of the customers was one of the better ways of acquiring the business knowledge. It is not claimed as a new discovery in the field of business but realized that it is more relevant in the context of Nepalese entrepreneurship also. In reality, customers are the representatives of the ‘field’ who have the power of accepting and rejecting the products. They inform the entrepreneurs about the rules and code of games to follow otherwise reject. The pace of time might be fast or slow of acceptance or rejection but the effect appears to the players.

Gopal stated an example of building relationships with business colleagues which creates the networks and platforms for sharing better ideas of business growth and continuation. He stated,

We have an organization ‘District Micro Entrepreneurs’ Group Association – DMEGA’ for raising the advocacy to ensure our rights and it also promotes the combined efforts of business activities (Gopal, Transcript, 30 September 2021).

Gopal utilized much to the network of DMEGA for involving to the collective efforts of business promotion and collecting new business ideas and skills. For him, the 'connection with other business colleagues is a better way of acquiring knowledge and skills of entrepreneurship.

Santosh also has the experience of involving to the entrepreneurs’ network. He stated, “I am a member of FNCSI since 2009 connecting to the members for sharing the business issues and creating mutual support” (Santosh, Transcript, 25 May 2021). From Santosh’s experience also, the action of coordinating and interacting with business peers and other parties seems to be a better way of acquiring knowledge and skills. The activities of coordination and interaction energize to form the formal/informal networks automatically.

Findings and Discussion

From the analysis of the experiences of the participants, the family or parental profession was one of the sources of entrepreneurial orientation. The sociologist, Walter (2014), concluded that the parent’s profession plays a significant role and was the primary source of socialization. As the source of primary socialization, Bourdieu insists that the dispositions which we acquire during childhood in family, and which ‘implanted’ a primary habitus in us, are ‘long-lasting’ and more decisive (Asimaki & Koustourakis, 2014). The family creates the environment, support and value structures, aspirations and family belief systems which all contributes to the foundation of the initial careers that starts the career legacy (Jackson, 2016). Another concept of transgenerational entrepreneurship, stated that the entrepreneurial mind-sets, in conjunction with “family-influenced” resources and capabilities, drive such value creation. These family-influenced resources include intangible resources, such as reputation, culture, and knowledge (Habbershon & Williams, 1999). It is important to note however those participants did state that, parents might play a negative role in preparing an entrepreneurial mindset as well. Morales-Alonso, Pablo-Lerchundi, and Vargas-Perez (2016) conducted an empirical study and they also concluded that the negative role models may be represented by parents who work as civil servants. This finding would therefore contribute to existing research on negative role models for entrepreneurship which were mainly represented by the failure entrepreneurs.

The experiences of entrepreneurs indicated that education and training are also important sources of entrepreneurial orientation and skills (Bhattarai, 2021; Bhurtel & Bhattarai, 2023). In fact, many of the entrepreneurs only initiated their businesses after participating in entrepreneurial training. Bourdieu (1984) suggested that the education, training and experiences are seen as a source of secondary habitus. The entrepreneurial orientation and skills are the cultural capital transferred by family interactions and the process of education; and may be institutionalized through educational qualifications (Walter, 2014). In fact, the entrepreneurs within this research study, who had a higher level of academic qualifications and participated in the training events, were seen as being highly skilled and successful entrepreneurs. This finding would therefore further support and contribute to the work of Subedi (2017) who concluded that educational qualification is a driving force to be oriented toward entrepreneurship. Parker and Praag (2006) have also found out that a highly educated entrepreneur results in better capabilities and performances for the firms (Parker & Praag, 2006).

Some of the participants of the study highlighted their experiences of entrepreneurial becoming and were motivated by the successful entrepreneurs within their familial circle and looked at them as role models. It has been argued that the exposure to role models has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intentions by providing specific guidance and support or by creating an environment that triggers entrepreneurial behavior (BarNir et al., 2011). The effects of different types of role models such as family, similar models and peers, educators and mentors, successful versus unsuccessful and unrelated models. In fact, Abbasianchavari and Moritz (2021) analyzed those types of role models based on 53 papers published in different journals and concluded that role models have a greater influence and contribution to the lives of new innovators and entrepreneurs.

The entrepreneurs valued the experiences of similar works as the source of business initiation. In social practice, the experience is also the means of secondary habitus or dispositions. The dispositions are ‘transferable’, which means the agents acquire and possess through their experiences (Corcuff, 2007). The entrepreneurial knowledge and skills are also transferable; hence, the entrepreneurs can shape their entrepreneurial dispositions and exhibit in the markets for competing with others. Therefore, having the relevant business knowledge assists in developing the entrepreneurial mindset (Shrestha, 2015). Furthermore, it was evident that entrepreneurs gather business knowledge from previous experiences within their career field (Bourdieu, 1986). The experiences enabled them to demonstrate the appropriate practices and strategies within their fields. Interestingly, many of the entrepreneurs referred to an interesting statement and said, “Work teaches work”.

Therefore, it could be said that habitus is durable, but changes due to the contextual experiences (Mayrhofer et al., 2007). Entrepreneurs who were seen as being “successful” role models were clearly a source of inspiration for many entrepreneurs. In fact, the entrepreneurs within this study were impressed and inspired to be the entrepreneur, as a consequence of the success of the popular entrepreneurs. Bourdieu (1990) suggests that through the experiences of everyday life (particularly formative experiences in the early years), individuals unconsciously adopt the social patterns and norms that surround them. Shrestha (2015) has also written the conclusion of his study that relevant business knowledge develops an entrepreneurial mindset and the ability to recognize problems and exploit opportunities.

From the analysis of the interview data, the study has concluded the sources of the entrepreneurial becoming in Fig. 1:

The researchers collected the experiences of the entrepreneurs regarding the ways of becoming. The narratives of the participants have indicated that the entrepreneurs followed different ways of acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge.

The narratives show that ‘observation’ is one of the ways of collecting entrepreneurial knowledge and skills. The entrepreneurs had the practice of observing designs, qualities, and the prices of competitors. They visited the markets, business expos, cultural events, and places to observe market demands, product types and other information relating to their business activities. They observed the products and/or services of other entrepreneurs, compared the products and made decisions accordingly. Therefore, observation and analysis of markets and competitors, amongst other things related to the business is one of the ways of acquiring orientation and skills. The entrepreneurs of MSEs observed others’ business activities with the view to learning new and better knowledge and skills. These ‘others’ can be understood as role models capable of influencing and reshaping the behavior of the observer (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, 2021).

Significantly, the experiences of the entrepreneurs within this research showed that they learned and accumulated a lot of business knowledge from their customers. They understood the needs and demands of their customers and looked for further suggestions/feedback from them to improve their entrepreneurial ventures. It was also a process of entrepreneurial socialization because individuals tend to maintain and perpetuate the dispositions ‘acquired’ through socialization (Jourdain & Naulin, 2011). Therefore, it was a way of shaping the habitus of the entrepreneurs, that incorporates the changing fashions, tastes, and interests of the customers, that are at the heart of each entrepreneurial venture. In fact, many entrepreneurs detailed how their consumers were very vocal in indicating the norms and expectations, regarding the products they expect from them and made reference to the ‘codes of music’ so that the entrepreneurs enacted their strategies in favor of the signals given by them.

The ultimate goal of a business is to maximize the customer satisfaction. If the number of satisfied customers increases, the business will flourish. Slater and Narver (1998) suggested that business should be customer-led and focused on understanding the expressed desires of the customers and utilize developing products and services that satisfy those desires. As Christensen and Bower (1996) pointed out that existing customers can substantially constrain a firm’s ability to innovate because the innovations may threaten the customers’ way of doing business.

Another way of learning about entrepreneurship is in the universities where many people enrolled in educational institutions (schools, colleges, universities, and training centers) for learning more about business skills. In this study, the participants shared their experiences of participation in general and skill training, as a result, they became more skilled and successful. Pallas (2000) found that people who go further through school are more engaged in the workplace, have more orderly careers, earn more money, and hold jobs with higher levels of prestige and status. For many successful entrepreneurs, the professional training has been as a key to their success, proves the existence of an ever-growing profession within the creative fields (Power & Scott, 2004). People with an entrepreneurial mindset want to participate to education or training in the field of enterprise and learn related knowledge and skills. Therefore, entrepreneurs learn business knowledge and skills even by participating in formal education and related trainings (Rai et al., 2020).

The entrepreneurs showed their experiences on entering the networks like DMEGA and FNCSI for making themselves capable of enacting their interventions successfully to the market – business field. Each field has its specific logic, traditions of necessary behavior, and networks of relations created and maintained by both individuals and institutions (Beames & Telford, 2013). The entrepreneurs had the experiences of engaging with social networks and securing their positions in the field. They have been implementing their strategic activities through these networks, for both sides of collecting resources and supplying the products to the markets. Sullivan and Marvel (2011) found that when entrepreneurs have more network ties the relationship between their knowledge and the number of workers employed is strengthened. The entrepreneurs have established connections with the business actors around them, within the social contexts to fulfill the objectives of “synergistic benefits for resource exchange and knowledge sharing” in entrepreneurial networks (Tsai, 2000). Likewise, connecting to the networks like producers’ networks is valued by the entrepreneurs and collect additional knowledge and skills. Networking extends the accessibility and enhance the abilities of the individual to capture resources that are held by others and so improve entrepreneurial effectiveness (Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Therefore, the experience of entrepreneurs and other studies on this area showed that the participation of entrepreneurs in such networks as a way of learning new knowledge and skills.

The study has identified the ways of entrepreneurial becoming and summarized in Fig. 2:

Conclusion

The entrepreneurs of MSEs informed about the sources of the entrepreneurial habitus - orientation, and skills. Entrepreneurs value sources such as family or parental profession, education and training, similar experiences, and impression of role models (successful personalities or entrepreneurs). Family and communities were clearly the sources of formative experiences for all of the individuals or groups involved within this research study. The entrepreneurial informants of this study clearly received and learnt their entrepreneurial orientation and skills from their parents and cultural peers, as well as through entrepreneurial education. In fact, it was evident that the educated and skilled entrepreneurs are capable competently dealing with the present market situation. The training packages directly help to start and support their enterprises. Likewise, this study clearly highlights that the entrepreneurial role model is also pivotal for successful entrepreneurs as a source of becoming an entrepreneur for some of the individuals.

The experiences of the entrepreneurs highlighted some of the ways of acquiring entrepreneurial orientation, knowledge, and skills. They had the experience of observing others’ practices, linking with networks, and listening to customers. The habitus of the entrepreneurs was shaped knowingly or unknowingly with the input received from the above-stated sources and the ways they perceived in the eyes of the entrepreneurs.