1. Introduction

The Indian startup ecosystem has demonstrated remarkable upsurge over the past decade, with nearly 120,000 registered startups as of 2023 (Invest India, 2023). It is projected that this number will double over the next several years. This ever changing entrepreneurship landscape has witnessed significant growth since business incubators have emerged as an crucial support system helping startups make their way through challenging process of ideation to sustainable growth (Awonuga et al., 2024; Page & Holmström, 2023). More than 950 incubators have surfaced nationwide to assist with this explosive growth in companies.

Business incubators are regarded as essential drivers of innovation and economic growth. They are created to give businesses the required resources, access to consulting services, networking opportunities (Aerts et al., 2007), mentorship and venture funding (Leitão et al., 2022), support for product and service development (Mian et al., 2016). By offering these resources and assistance, business incubators are intended to reduce the high startup failure rates by providing necessary resources and assistance. Morever, even after the incubation period is over, startups that have gone through the process will still have a better chance of surviving and expanding than those that haven’t (Schutte & Direng, 2019). Proponents of business incubation often highlight its benefits, but they do not guarantee that businesses will succeed through their support (Bruneel et al., 2012).

The basic idea is that incubators may greatly raise the chance of business success by reducing entry barriers and offering a supportive atmosphere. However, the way through these incubators is not without challenges. Within these supportive settings, startups frequently face major difficulties that might obstruct their development and, in rare circumstances, cause their early failure. This study explores the complex problems entrepreneurs experience in business incubators, illuminating the operational and systemic challenges that may hinder their success. Furthermore, many researchers have highlighted major knowledge gap on business incubators despite ample scholarly research on their various typology of incubators and their economic aspects (Hausberg & Korreck, 2020; Leitão et al., 2022) . The majority of incubation studies appear to be more concerned with the process of incubation than with the wants and expectations of the incubatees (Ahmad & Thornberry, 2018; Jones et al., 2021; McAdam & McAdam, 2006). Specifically, there is a dearth of literature on firsthand experiences of entrepreneurs during the incubation period. This research uniquely emphasizes the entrepreneur’s perspective on challenges faced within incubators. Thus, the study aims to answer the following research questions

RQ1: What are the major challenges startups face during the incubation phase?

RQ2: How are these challenges faced by startups during incubation interrelated?

This study makes a unique contribution by methodically looking at the issues firms face when participating in incubation programs. It explores the complex realities of entrepreneurs navigating various contexts using qualitative observations. Ultimately, it promotes the expansion and success of startups by deepening our understanding of the incubation process and educating entrepreneurs, incubator managers, and policymakers on the best ways to handle these challenges.

The study’s remaining sections are arranged as follows. The next section provides a summary of previous research, emphasizing key studies and conclusions that have shaped the current understanding of the field. This is followed by a detailed description of the methodology used for the study. Subsequently, the results and analysis are presented, along with their implications. The concluding section summarizes the study. The last section highlights its limitations, and suggests areas for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Incubation Process

“A startup is a newly established business that aims to solve a problem or fill a market gap under conditions of extreme uncertainty, often prioritizing rapid growth and scalability over traditional organizational structures” (Blank & Dorf, 2020). Startup’s success can be impacted by human, entrepreneurial and financial capital, all of which are crucial factors for growth and sustainability (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004). Incubators, as essential component of startup ecosystem act as an effective intermediary by providing these factors to foster startup growth (Bruneel et al., 2012). Incubators vary in their selection criteria, offered services, and the ecosystem linkage they provide to startups based on the type of startup they support (Bergek & Norrman, 2008). Nevertheless, all incubators provide a mix of services, including networking opportunities, access to physical resources, financial access, process support, and business support services, (Pauwels et al., 2016). These services foster an environment that is conducive to the success of startups. This framework has been elaborated upon in recent research, highlighting the growing significance of customized support that considers the unique requirements of various kinds of endeavors. For instance, incubators that concentrate on technology can offer cutting-edge lab space and connections to tech-specific networks (Silva et al., 2023). At the same time, those who support social enterprises might be more concerned with effect assessment and community involvement. Incubators serve as a link between the industry and the community, encouraging the development of creative ideas and offering financial support, professional assistance, inspiration, and resilience in times of adversity (Guerrero et al., 2021).

2.2. Impact on startup Success

Incubators are vital in promoting the areas’ economic development. Page & Holmström (2023) found that startups in incubators are more likely to achieve sustainable growth than those not in incubator programs. Braun and Suoranta (2024) reported that incubated firms grew faster than non-incubated ones due to improved financial planning and strategic alliances fostered by incubators. Hassan (2020) highlighted that the workshops and collaborative office areas provided by incubators enable businesses to leverage common expertise, hence increasing creativity and efficiency. A common metric used to assess an incubator’s efficacy is the tenant companies’ level of success (Torun et al., 2018). By offering vital resources and support networks, incubators can significantly lower the startup death rate, as noted by Bergek and Norrman (2008). On this issue, the outcomes of recent empirical investigations have been inconsistent.

Compared to non-incubated firms, incubated startups have greater survival rates and are more likely to draw funding, according to some studies. Other research, however, indicates that the advantages might not apply to all incubators and business endeavours. It’s crucial that the incubator’s mission and the startup’s requirements line up. For example, a startup’s performance is significantly influenced by its network connections, industry specialisation, and mentorship quality (Ahmad & Thornberry, 2018).

2.3. Challenges faced by startups

Entrepreneurs frequently face a variety of difficulties in a complicated and unpredictable environment while trying to secure a competitive edge (Pereira et al., 2021). Past Research shows that small enterprises, which frequently have fewer resources, have a harder time staying in business and are more prone to losing investors and customers (Breivik-Meyer et al., 2020; Vinberg & Danielsson, 2021). Startups face a number of challenges throughout their lifecycle, chief among them are financial and bureaucratic ones (Ferreira et al., 2017; Pareras, 2021), human capital issues (Bendickson et al., 2017), identifying marketable opportunities (Fini et al., 2020), and absence of crisis management expertise. This is because the teams in these ventures usually have less experience, which makes it more difficult for them to handle crises (Salamzadeh & Dana, 2021). In such cases, business incubators play a vital role in helping startups survive and flourish (Schutte & Direng, 2019). Despite the support provided by incubators, the effectiveness of incubation varies. Van Rijnsoever and Eveleens (2021) found that the quality of services offered by incubators differs significantly, with some lacking adequate resources and trained mentors, which exacerbates the operational challenges faced by startups and impacts their overall performance.

Incubators are changing how they function due to a number of new trends that are constantly changing the landscape of business incubation. Incubators were compelled by the COVID-19 pandemic to switch to hybrid models. According to Vaz et al. (2022), incubators that provided both virtual and in-person support were able to sustain higher levels of engagement. Growing virtual incubators, which provide traditional incubator services via online platforms, is one notable trend (Freiling et al., 2022). With increased accessibility and flexibility for businesses, this model has gained popularity, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. Many businesses were negatively impacted, and numerous ones were unable to withstand the economic difficulties brought on by the pandemic (Vasiljeva et al., 2020). Usman & Sun (2023) emphasised how digital platforms help companies become more adaptable and increase their access to international markets.

A lot of incubators now include sustainability and social effects in their selection criteria and support services, as there is now an increasing focus on these topics. Although the goal of business incubators is to help businesses grow, there is strong evidence that startups nevertheless face difficulties while participating in these initiatives (Lose et al., 2016). Regardless of their original design and function, incubators must continually adapt to environmental changes to remain relevant and effectively support startups in overcoming these challenges (Bruneel et al., 2012; Pauwels et al., 2016).

Financial Challenges

Financial difficulties including reduced budgets and cash flow issues make it tough for startups to sustain themselves, and the pandemic has made funding more erratic because of cautious, risk-averse investors (Salamzadeh & Dana, 2021). In this situation, business incubators are vital because they offer entrepreneurs the necessary assistance to get through these financial challenges. Tengeh and Choto (2017) revealed that the major challenges faced by incubatees were a deficiency of seed funding and continuous financial support. Startups often struggle with product development, growth of their operations, and to remain in business without sufficient finance. Lose et al. (2016) highlight the financial obstacles as well, pointing out that a large number of South African startups are unable to obtain adequate capital from lenders or investors. Their inability to raise money makes it difficult for them to compete and expand in the market. The dearth of startup funding in Europe is also widely known (Bottazzi & Da Rin, 2002).

Access to market & competition

Small businesses are at serious risk from the pandemic since decreased demand necessitates a change in marketing strategies (Salamzadeh & Dana, 2021; Vinberg & Danielsson, 2021), underscoring the necessity of business incubators to assist in navigating these adjustments.

Entrepreneurs at incubators in Western Europe are not well-versed in consumer outreach, personnel management, investor pitching, or business management (Van Weele et al., 2018). Tengeh and Choto (2017) state that it can be challenging for startups to break into established markets and connect with potential clients. This is made worse by the fierce competition they encounter from both new startups and well-established businesses. The “liability of newness,” as discussed by Mireftekhari (2017), alludes to the suspicion that new endeavours frequently encounter from outside stakeholders. This mistrust can further restrict a startup’s access to the market by making it difficult for them to win over partners, investors, and customers.

Lack of business knowledge & Management skills

One subject that appears frequently in the literature is a lack of business expertise. Many entrepreneurs lack the ability and know-how to run and expand their companies. Tengeh and Choto (2017) highlight this as a major obstacle, pointing out that insufficient business acumen can result in bad choices and strategic mistakes. A disparity in managerial qualities among incubatees is also noted by Lose et al. (2016). According to their argument, incubators should offer more comprehensive training and mentorship to assist businesses in acquiring the skills necessary for success.

Unavailability of support services

The absence of support services in business incubators is a substantial obstacle to the growth and success of businesses. (Woolley & MacGregor, 2022) assert that crucial services like mentorship, company development, and finance access are necessary for incubatees to succeed. Startup failure rates may increase and the incubator’s overall efficacy may decrease without these services. Research emphasises how crucial it is for incubators to offer thorough, specialised support that is matched to the requirements of each enterprise (Vanderstraeten et al., 2016). Without these services, businesses could struggle with issues including scarce resources, difficult market access, and inadequate strategic direction, which would eventually impede their capacity to develop and remain viable over the long run. The gap caused by entrepreneurs’ limited understanding of business is intended to be filled by services offered by incubators such as accountancy, patenting, advertising, financial support and legal advice (Blackburne & Buckley, 2017).

Absence of Physical Infrastructure

Sufficient physical infrastructure is essential to startups’ daily operations. According to Kuryan et al. (2018), incubators have a favourable impact on a business’s organisational characteristics by offering infrastructure. But a lot of incubators don’t have enough space. Tengeh and Choto (2017) concur, pointing out that inadequate infrastructure can restrict the output and expansion of new business. Virtual incubators are more accessible and flexible than traditional incubators, even if traditional incubators provide more tangible resources and a collaborative setting (Vaz et al., 2022). virtual incubators should develop new ways to imitate the advantages of online physical presence, such as by offering strong digital platforms and building vibrant online communities to mitigate challenges posed by absence of physical infrastructure (Freiling et al., 2022).

Ineffective Incubator Management

Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009) concur that productivity and ongoing growth in human resources are among the most valuable assets of any organization. Gulia et al. (2024) identified incubator management as a crucial factor of business incubator influencing the success of incubation process. Therefore, it is crucial for the incubator manager to foster creativity and innovation within the functions of business incubation (Rice, 2002). Ensuring smooth support for companies in incubators requires efficient management (Wasdani et al., 2022). Inefficiencies, however, might result from subpar management techniques. Lose et al. (2016) claim that incompetent incubator management might hinder companies’ access to support, which can have an impact on their overall growth.

Internal Organization Challenges

Although incubators offer a variety of tools to the businesses they assist, they frequently fall short in providing resources that are primarily targeted at internationalisation, particularly with regard to networking (Drennan et al., 2020). Organisational problems within are also common. According to Mireftekhari (2017), formal structures and processes are frequently absent from startups, which can result in inefficiencies and operational difficulties. This “internal liability of newness” implies that startups may find it difficult to successfully organise themselves and carry out their business strategies, even with outside assistance. Gobble (2018) presents a significant aspect of the psychological and cultural obstacles that startups encounter, especially in high-stress settings such as Silicon Valley. The constant pressure to succeed sometimes results in high levels of stress and mental health problems for founders. In an effort to achieve deadlines and produce desired outcomes, founders may turn to questionable methods, which can result in fatigue, depression.

Exclusionary cultural environments can also exist. Gobble (2018) points out that it can be challenging for minorities and women to secure a spot in the startup ecosystem since they frequently encounter additional obstacles. This lack of diversity has the potential to hinder creativity and reduce the talent pool that startups have access to.

3. Methods

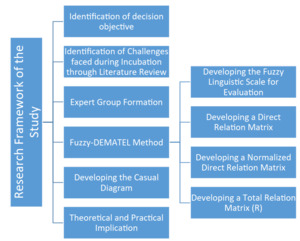

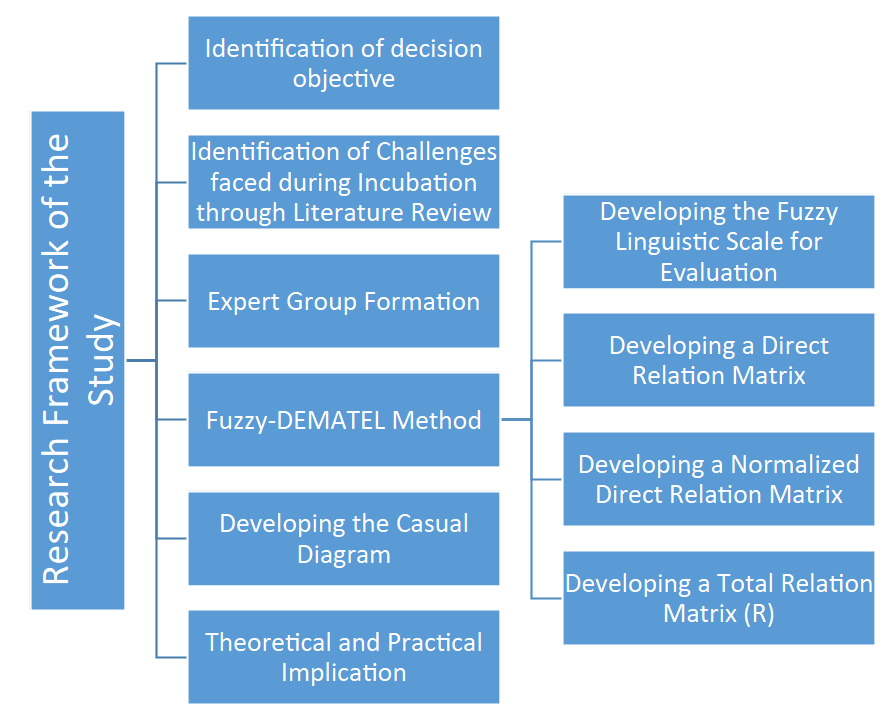

The literature review examined the significant challenges faced by startups during incubation, while the Fuzzy-DEMATEL examined the connections among these obstacles. This section delves more into the stepwise process, which is summarized in Figure 1. The DEMATEL technique was chosen as it analyses complex causal relationships between variables effectively when the data contains subjectivity or ambiguity.

3.1. Data Collection

The hybrid Fuzzy-DEMATEL method used in this study relies on data collected by consulting experts. A questionnaire was developed to address the Fuzzy-DEMATEL methodology’s requirements for data collection. In the first segment of the questionnaire, the goal of the research was explained along with brief description of challenges. It also collected demographic information of experts such as area of expertise, professional background and position in the organization. The experts were asked to assess the impact of different variables on each other on a given scale in a matrix in the subsequent section. This method does not necessitate the large-scale primary data collecting that survey-based research entails (Parmar & Desai, 2020).

The complexity of the study and the availability of suitable experts will determine how many experts are needed for the Fuzzy DEMATEL technique’s data collection. However, in order to guarantee a varied and trustworthy variety of perspectives, it is often advised to include five to ten professionals. However, studies in the past (Kumar et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020) have also used similar methodology with expert sample size four. This range is recommended for having a well-rounded panel of specialists which guarantees a wide range of in-depth insights. Shieh et al. (2010) maintain acceptable group dynamics and data processing while balancing the requirement for a suitable breadth of knowledge. Experts were selected according to their work experience, educational background, and professional background in business incubation. Nine experts, comprising academicians, incubator graduates, managers, and consultants agreed to participate in the study. Academicians (four) in the sample were engaged in new venture creation and/or entrepreneurship research. Two of the experts are academicians in the fields of new venture creation and entrepreneurship development at an Indian national institute, while the other two specialise in business environment and strategy at two of the country’s best private colleges. None of the academicians participating in the study were affiliated to our institute to ensure impartiality in the research process. The other expert serve as a consultant for a prominent government-funded incubator in India while another holds the position of an incubator manager at a university based business incubator. The other experts are graduate entrepreneurs from various business incubators. The experts responded using the linguistic perception scale.

3.2. Fuzzy-DEMATEL method

The DEMATEL method illustrates the fundamental idea of contextual links and the relative influence of elements within a system through structural modelling tools, such as directed graphs and causal diagrams. According to each variable’s degree of influence, the DEMATEL technique creates a cause and effect diagram (Lamba & Singh, 2018). This method aids in identifying how the various parts of the system are interdependent (Wu & Tsai, 2012) .

Fuzzy set theory is an efficient tool for measuring linguistic expressions and the fuzzy concepts linked with human judgements (Dubois & Prade, 1980; Islam et al., 2018). The study used hybrid Fuzzy-DEMATEL technique as it measures the strength of interactions and provide insight into both influencing and influenced variables (Tzeng & Huang, 2011). Decision-making criteria are made more difficult by human perception’s inherent ambiguity and vagueness. According to Saaty (1980), the integrated method is advantageous in handling the ambiguity arising from human subjective impressions. It reduces the possibility that human judgments would contain erroneous or missing information (Kazancoglu et al., 2018). The next subsection goes into detail about the process.

3.2.1. Step 1: Identification of decision objective/ Identifying the decision goal and forming a committee

The decision-making process includes the following steps: outlining the objectives of the decision, gathering pertinent information, identifying potential alternatives, weighing the pros and cons of each, choosing the best option, and keeping track of the outcomes to determine whether the objectives of the decision are met or not.

A thorough literature analysis was used to identify the variables affecting the system objective. Experts with the necessary experience and expertise were then consulted. After the variables had been agreed upon, the expert panel was given a survey to evaluate the correlations between the variables. After that, as shown in Table 2, the experts were asked to apply their knowledge to ascertain the variables’ relative influences through language perception.

3.2.2. Step 2: Development of evaluation criteria and formulation of the fuzzy linguistic scale

Owing to the way the criteria contain cause-and-effect interactions, they involve a lot of intricate details. To separate the important criteria into cause and effect groups, a structural model should be built using the DEMATEL approach. Five linguistic phrases which are expressed as positive TFN (lij, mij, rij), are used to represent the degree of effect of each criterion over others in order to address the subjectivity and vagueness of human judgement: no influence (No), very low influence (VL), low influence (L), high influence (H), and very high influence (VH). This linguistic perception scale is called a triangular fuzzy number (TFN). TFN symbolizes the linguistic perception scale’s values. Using TFNs, the direct relation matrices (DRMs) are transformed into fuzzy assessment matrices.

3.2.3. Step 3: Developing a normalized direct relational matrix

The CFCS approach subsequently defuzzifies these fuzzy assessments into crisp values, zij (Lin & Wu, 2008). Consequently, the formulas (1) to (5) obtain the direct relation matrix Z=[zij]n×n

\[ x l_{i, j}^k=\left(l_{i, j}^k-\min l_{i, j}^k\right) / \Delta_{\min }^{\max } \]

\[ x m_{i, j}^k=\left(m_{i, j}^k-\min m_{i, j}^k\right) / \Delta_{\min }^{\max } \]

\[ x r_{i, j}^k= \left(r_{i, j}^k-\min r_{i, j}^k\right) / \Delta_{\min }^{\max } \tag{1} \]

Where

Determine the normalized values on the left (ls) and right side (rs):

\[x{ls}_{i,j}^{k}= {xm}_{i,j}^{k}/(1+ x m_{i,j}^{k}- x l_{i,j}^{k})\]

\[x{rs}_{i,j}^{k}= {xr}_{i,j}^{k}/(1+ x r_{i,j}^{k}- x m_{i,j}^{k})\tag{2}\]

Calculating the crisp values:

\[ x_{i, j}^k=\frac{\mathrm{x} l s_{i, j}^k\left(1-\mathrm{x} l s_{i, j}^k\right)+\left(x r s_{i, j}^k\right)^2}{1-x l s_{i, j}^k+x r s_{i, j}^k}\tag{3} \]

Total normalized crisp values:

\[ z_{i, j}^k=\min l_{i, j}^k+x_{i, j}^k \cdot \Delta_{\min }^{\max }\tag{4} \]

Integrating crisp value by:

\[z_{i,j}= \frac{1}{p} ( z_{i,j}^{1}+z_{i,j}^{2}+.....+z_{i,j}^{p}),\tag{5}\]

Where p represents the number of individuals involved in decision making

3.2.4. Step 4: Obtaining and evaluating evaluations of decision makers

The total relation matrix (R) can be calculated using the formula below:

\[R\ =\ N\ (I\ −\ N)^{−1}\]

“I” stands for the matrix of identity.

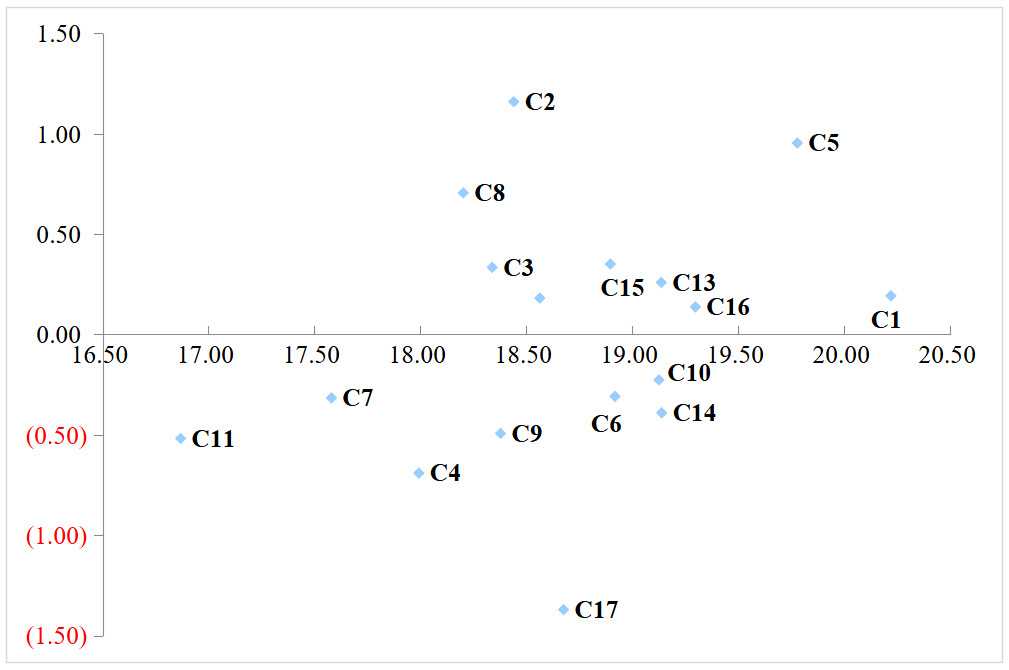

3.2.5. Step 5: Development of causal diagram

The horizontal axis (D+R) in the causal diagram created using the Fuzzy DEMATEL approach is called “Prominence” and it shows the overall relevance of each variable. “Relation” is the vertical axis (D-R) that divides variables into categories based on causes and effects. The variables that exhibit a positive (D-R) value are classified as causal, signifying their significant impact on other factors. Factors that have a negative (D-R) value, on the other hand, belong to the effect group and are therefore more influenced by other factors. Understanding the impacts and interdependencies between the variables is made easier by this classification.

4. Analysis and Results

A total of seventeen challenges faced by startups in business incubators were identified. Experts specialized in business incubation were contacted using the procedure outlined in Section 3.1. Following the finalization of the barriers, the experts were tasked with evaluating their impact via the lens of language perception. The five linguistic information (least influence, less influence, moderate influence, strong influence, and very strong impact) stated as positive TFN (lij, mij, rij) were utilised with the linguistic perception “Influence” (see Table 2).

As seen in Table 3, the experts’ responses were given as Decision-making matrices (DRMs). In the same way, DRMs were gathered from eight more specialists. Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs) were used to convert these matrices into fuzzy assessment matrices, which took into consideration the inherent uncertainty in the judgements. The other matrices were converted into Fuzzy DRMs in the same way. The other matrices were converted into Fuzzy DRMs in the same way.

The fuzzy data was then transformed into precise values, and Zij was used to represent the final precise value. Equations (1) through (5) in Section 3.2 were used to determine the normalised DRM. Using Eq. (6), the entire direct relation matrix (R) was obtained and is shown in Table 5. The terms “prominence” (D + R) and “relation” (D-R) were calculated by adding up the rows (D) and the columns (R). As shown in Table 5, variables with negative (D-R) were classified as effects and those with positive (C) as causal. D+R shows the total influence of the variable on the system. This value shows how much of an overall impact a variable has on the system. It is the total of the impacts (R) that other variables provide to a variable and the direct influences (D) that a variable has on them. In essence, 𝐷+𝑅 shows the degree to which a variable works as both a cause and an effect on all other variables in the system. A high (D+R) number indicates a high level of systemic interaction for the variable. A low (D+R) value on the other hand suggests that there aren’t many interactions between the variable and the system. It is not greatly influenced by many variables, nor does it strongly influence numerous variables.

As seen in Fig. 2, a causal association graph was created by plotting these values.

5. Discussion

By modelling system variables and investigating how each one affects the system as a whole, the hybrid Fuzzy-DEMATEL approach made it possible to identify the key challenges faced by startups during incubation period. We can determine which challenges have the most influence and which are more influenced by others by looking at the cause-and-effect linkages among these challenges. This facilitates setting priorities for activities and efficiently allocating resources.

The table 5 presented summarises the cause and effect linkages among the challenges. The variables were categorised based on their relation (D-R) and prominence (D+R) values. Cause group challenges have a positive (D-R) value, denoting that they strongly influence other barriers instead of being influenced. Among the major challenges noted in this group are “High incubator rent” (C8), “Poor incubator administration” (C5), “Unavailability of required services” (C3),“Lack of capital and required funds” (C2), and “Lack of business knowledge and essential skills” (C1).

“Poor Incubator administration” (C5) has the greatest value of (D-R) of all the variables in the cause group, suggesting that C5 has a major influence. Out of all the causative variables, C5 has the highest degree of influence (10.3). Poor Incubator administration has also been identified in prior research as a major challenge (Wasdani et al., 2022).The study’s results indicate that it substantially impacts other variables; therefore, improving C5 will help the system as a whole. Therefore, to ensure smooth support for startups in incubators requires efficient management. In conclusion, C5 is a significant challenge startups face during the incubation period.

C1, i.e., “lack of business knowledge and essential skills,” is the second-highest (D-R) variable. Upon closer examination of the indices in Table 5, its (D + R) value is the highest at 20.21 and the second highest influence (10.2). This is in line with the research conducted by (Vardhan & Mahato, 2022). Startups frequently struggle with a lack of business expertise and critical skills during the incubation phase, which can have a big impact on their success. As a result, C1 has major influence on the entire system and can be grouped as a powerful barrier. Building a supportive network, utilising outside resources, and taking a proactive attitude to learning and growth are all necessary to meet this challenge. Startups can improve their chances of success and better manage the intricacies of business by concentrating on gaining the required knowledge and skills.

The “lack of capital and required funds” is the third significant variable (C2). It has an extremely low (D + R) value. C2 has a low value of (D + R) due to its relatively high influential impact and modest take-away from others, as indicated by its D and R values. Due to variable C2’s significant effects on the entire system, the comparatively low value of (D + R) was unable to compete. This concur with Silva et al., 2023. The study concluded that it is imperative that the issue of capital shortages and required cash be addressed for businesses to be successful during the incubation stage. Thus, with the utilization of incubator resources, intelligent financial planning, and a range of funding sources, businesses can surmount this obstacle and put themselves in a position to achieve long-term success and growth.

“Unavailability of required services” (C3), forms the other Cause Variable (D-R=0.3). (Zhang et al., 2022) also points out lack of essential services in business incubator as a significant challenge for startups. Operational efficiency depends on providing basic services (such as legal, accounting, and mentoring). It is possible to improve overall startup performance by making services more accessible.

Next cause variable is “High Incubation rent” (C8), with a (D-R) value of 0.7078. Its second-highest rating of 4.1964, represents its maximum level of influence. According to Diedericks, 2015, high rent is one financial expense that can put a strain on a startup’s limited funding. Resolving issue can enhance the sustainability and financial health of startups.

Even though challenges such as, “Difficulty faced in locating market for the business” i.e., C12 (0.1833), “Difficulty in acquiring the supply/raw material for business” i.e., C13 (0.2616), “Too much administration work” i.e., C15 (0.3530), “Difficulty in managing the cash flow” i.e., C16 (0.1398), and “High Incubation rent” or C8 (0.7078) are not as important as C1, C2, or C5, they nevertheless have a significant impact on the system as a whole.

Effect group factors depend on other system variables so they cannot be deemed significant. To comprehend the features of these effect variables, it is crucial to discuss them. This group of challenges’ (D-R) value is negative, suggesting that other barriers have a greater influence on them. Key challenges included in this group are:

“Lack of physical infrastructure” C4 with a (D-R) value of -0.6884 is an effect variable. C4’s prominence value (17.9903) indicates that it is strongly impacted by other challenges, meaning that removing higher influence barriers is necessary to resolve it. Mian et at., 2016 highlighted that financial and administrative difficulties encountered during incubation phase frequently have an impact on physical infrastructure. Improving infrastructure support can help startups a lot.

Challenges like “Incompetency of staff at the incubator” C6 (-0.3063), “High operational charges for the services” C7 (-0.3134), “Competition from other startups” C9 (-0.4906), “Trouble in managing business finance” C10 (-0.2241), “Difficulty faced for acquiring a license for the business” C11 (-0.5159), “Difficult to follow business plan” C14 (-0.3879), and “Difficult to claim the reimbursement” C17 (-1.3686) are although influenced by other variables, indicate areas that need to be resolved indirectly. Particularly, C17 has the highest negative (D-R) value and is heavily influenced by other factors; hence, lowering higher influence barriers would likely have a major negative impact on the problems that C17 poses. Silva et al., 2023 also found that administrative effectiveness has a big influence on reimbursement procedures. This strain can be considerably reduced by streamlining these procedures.

6. Implications

This section discusses the study’s theoretical contribution followed by managerial implications. By addressing these theoretical and managerial implications, incubators can establish a more conducive atmosphere that not only lessens the difficulties faced by entrepreneurs but also promotes their sustainability and long-term success.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The present study advances the theoretical framework by tackling the existing literature needs (Lee et al., 2023) for an in-depth investigation into the challenges encountered by startups in business incubators from entrepreneur’s perspective.

The study identifies with the RBV approach by the recognition of challenges as causes, such as lack of critical factors like financial resources, effective management and essential business knowledge during the incubation phase. To acquire a competitive edge, startups must manage and secure essential resources. The way that incubators help or hinder the acquisition and administration of these vital resources can be added to the RBV theory. The study underpins the importance of effective management to tackle incubation challenges. It indicates that incubators should strengthen the internal capacities of startups by offering capacity-building programs that fortify the businesses’ own resource bases in addition to direct assistance. This entails providing thorough instruction, mentorship, and financial support. Incubators can aid in the development of long-term competitive advantages for companies by overcoming resource limitations. This theoretical insight enhances the RBV framework by highlighting its strategic importance in early stage of startup development.

This study emphasises the vital role that incubators play in helping businesses build important connections and relationships by utilising network theory. It identifies the “Unavailability of required services” as a primary challenge, indicating deficiencies in the network support provided by incubators. The study demonstrates that strong network connections can facilitate access to outside resources that are critical for business survival and expansion, including financial, legal, and marketing services. It emphasizes the significance of incubators serving as intermediaries between entrepreneurs and external parties, such as industry professionals, possible financiers, and service suppliers. By offering a sophisticated understanding of how network dynamics affect startup success, this contribution broadens the relevance of network theory in the context of incubation.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The study offers practical insights from the management standpoint to improve the incubation process and results for entrepreneurs and incubator management. Considering that “Lack of business knowledge and essential skills” is a cause variable, incubators must invest in extensive training and development initiatives. Business skills like financial management, market research and strategic planning covered in these programs provide startups with the know-how they need to succeed on their own (Borges & Silva, 2022). Business incubators require better financial support systems due to the significance of “Lack of capital and required funds” as a cause. It is recommended that incubators investigate diverse funding alternatives, including grants, low-interest loans, and investor networks, in order to furnish entrepreneurs with the requisite financial means. Furthermore, well-defined policies for allocating resources can aid businesses in more effectively handling their operational requirements (Page & Holmström, 2023). To address the issue of “Unavailability of required services”, incubators ought to collaborate with service providers to guarantee that startups have access to essential services like accountancy, legal counsel, and IT help. Establishing a network of dependable service suppliers for startups can greatly ease operating issues.

The findings also reflect that regular networking events can improve startups market presence and growth prospects by establishing connections with possible partners, investors, and customers. Initiatives such as industry gatherings, networking events, and market access programs to address issues with market access, such as “Difficulty faced in locating market for the business”. Identifying and strengthening technical expertise as a core competence is crucial to attracting high-quality entrepreneurs to the incubator (Jha & A, 2024).

7. Conclusions

The research emphasizes the importance of tailored support system in order to successfully handle the major obstacles that startups face throughout the incubation phase. The study conducted a thorough literature analysis in order to identify and analyse the significant challenges a startup encounter during incubation to answer RQ1. A total of seventeen challenges were identified, namely, “Lack of business knowledge and essential skills”, “Lack of capital and required funds”, “Lack of physical infrastructure”, “Poor Incubator administration”, “Incompetency of staff at the incubator”, “High operational charges for the services”, “High incubator rent”, “Competition from other startups”, “Trouble in managing business finance”, “Difficulty faced for acquiring a license for the business”, “Difficulty faced in locating market for the business”, “Difficulty in acquiring the raw material for business”, “Difficult to follow business plan”, “Difficult to follow business plan”, “Too much administration work”, “Difficulty in managing the cash flow”, “Difficult to claim the reimbursement”

The issues that startups encountered during incubation were divided into cause and effect variables based on the analysis conducted using the fuzzy DEMATEL technique. The causal diagram identified five significant challenges that had an influence. The causes that were discovered were “lack of business knowledge and essential skills,” “lack of capital and required funds,” “poor incubator administration,” “incompetency of staff at the incubator,” or “high operational charges for the services.”

In response to RQ2, a causal diagram was developed by categorizing these seventeen challenges into cause and effect variables. The cause-and-effect links demonstrate the intricate interactions between these several variables that affect the development and success of incubated firms. The five major cause variables identified by the diagram were “lack of business knowledge and essential skills,” “lack of capital and required funds,” “poor incubator administration,” “incompetency of staff at the incubator,” or “high operational charges for the services.” These cause variables have a major impact on other variables, resulting in major effect variable, "Trouble in managing business finance and “Difficult to follow business plan.”

By addressing these primary concerns, it is possible to improve a number of effect variables and, hence, improve the incubation experience for entrepreneurs. By addressing these crucial issues, incubators may offer a more conducive environment that encourages the growth of startups. This study highlights the significance of addressing both the resources offered by incubators and the unique needs and problems of the incubatees to establish a more conducive environment for entrepreneurial success.

8. Limitations and Future Scope

The study has a few limitations in terms of subjective bias due to participant’s perception, knowledge and business incubation competence. Also, there are limitations based on the sources of the past literature used and the selection of experts for the research might affect the reliability of the findings, indicating need for further research. Lastly, the study’s emphasis on the Indian startup ecosystem may limit the generalization of conclusions to other areas with different regulatory and economic conditions. Future research could gain valuable insights from longitudinal studies that track how these challenges develop over time. Additionally, sector-specific research could be conducted to enhance the authenticity and relevance of the viewpoints.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

Authors thanks and acknowledge the support of National Institute of Food Technology Entrepreneurship and Management (NIFTEM), Kundli, (Communication Number: NIFTEM-P-2024-78), Sonipat.