Introduction

Resilience has garnered increasing interest across numerous academic fields, including safety (Wildavsky, 1988), crisis management (Linnenluecke, 2017; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003), terrorism and civil unrest (Herbane, 2010), natural disasters and pandemics (Battisti & Deakins, 2017; Belitski et al., 2022). The growing frequency and severity of global crises have intensified this scholarly attention (Barasa et al., 2018). Despite extensive research, literature about resilience remains fragmented, characterized by diverse conceptualizations and persistent definitional and conceptual ambiguity (Ungar, 2011). For instance, Hillmann and Guenther (2021) identified as many as 71 distinct definitions, reflecting significant theoretical and empirical challenges that complicate consistent study across disciplines (Linnenluecke, 2017).

In business studies, resilience and entrepreneurship are not only closely related (Ayala & Manzano, 2014), but entrepreneurship itself is often perceived as an expression or outcome of resilience, especially when it emerges because of crisis or adversity (Hayward et al., 2010). Resilience research initially focused predominantly on organizational responses to change, adversity, and crisis from evolutionary and systems perspectives (Duchek, 2020; Staw et al., 1981). More recently, with the rapid growth of entrepreneurship research, a significant body of literature has emerged emphasizing resilience as crucial for entrepreneurs and small businesses facing adversity, enabling recovery, adaptation, and even transformation (Fisher et al., 2016; Korber & McNaughton, 2017; Williams et al., 2017). Entrepreneurial resilience, broadly defined as entrepreneurs’ ability to withstand and learn from business setbacks and disruptions to ensure venture continuity and growth (Ayala & Manzano, 2014), has thus become a key research domain within the entrepreneurship discipline. understanding female entrepreneurial resilience requires recognizing how inequality is embedded in social structures through power dynamics, leading to differential access to resources for men and women (March et al., 1999). Such inequalities extend to women’s managerial decision-making and entrepreneurial opportunity recognition and exploitation, as they limit women’s agency (Kabeer, 1999). Thus, resilience does not just relate to individual differences but to deeply institutionalized inequalities via social norms, cultural practices, and legal systems that systematically disadvantage women (Hunt & Samman, 2016).

Nonetheless, comparable to entrepreneurship research, equally discursive practices in resilience studies remain implicitly male-dominated (Ahl, 2006; C. Brush et al., 2009). Despite the expansion of resilience scholarship, it remains largely gender-blind or treats gender superficially at best (Branicki et al., 2018; Smyth & Sweetman, 2015). Ahmed et al. (2022), for example, conducted a critical review of 125 entrepreneurship studies on resilience, stress, and coping but notably failed to consider gender explicitly, despite highlighting contextual factors and prior life experiences. Such gender omission parallels early entrepreneurship research trajectories, where women’s perspectives were often neglected, and gender was treated merely as a peripheral variable (Ahl, 2006; Jennings & Brush, 2013; Marlow, 2002). This absence significantly limits understanding of how gender dynamics, including societal expectations, role constraints, and institutional biases, influence entrepreneurial resilience. This gap has only recently begun to be addressed. A 2024 systematic literature review on resilience as a key success factor in women-led businesses by Hernández et al. (2024) highlights that resilience is a critical determinant of venture success, enabling women business owners to navigate obstacles and achieve growth, even as it reveals how underexplored this topic remains in entrepreneurship research.

Accordingly, the paper proceeds as follows: First, the study reviews the existing literature on entrepreneurial resilience and clarifies key definitions to provide a foundation for our gender-focused analysis. Second, this research examines the gendered dimensions of entrepreneurial resilience by drawing on empirical evidence of how women entrepreneurs experience resilience across three critical domains: small business survival, financial management, and strategic adaptation. Third, informed by these insights, this study critically evaluates prevailing resilience frameworks, trait-based, cognitive-behavioral, and process-based, to assess their capacity to account for gender dynamics, structural constraints, and intersectionality. In response to the gaps identified, this study proposes a comprehensive, gender-sensitive resilience framework that reconceptualizes resilience as a dynamic process integrating gendered coping mechanisms, structural barriers, and intersectional dimensions. Fourth, this research discusses the practical and policy implications of the recommended framework, including suggestions for targeted interventions (e.g., inclusive training programs, networking support, and institutional reforms) to strengthen the resilience of women entrepreneurs and outline avenues for future research. Finally, the research concludes by summarizing the study’s contributions and acknowledging its limitations, highlighting in particular the need to apply an intersectional lens and conduct empirical validation of the model across diverse contexts.

Entrepreneurial Resilience

Resilience, within the context of small business and entrepreneurship, has emerged as a critical area of study (Battisti & Deakins, 2017), driven largely by increasingly volatile markets, resource scarcity, and intensified competition. For small firms, where strategic and operational responsibilities typically rest on the entrepreneur or founder, resilience is pivotal for organizational survival and long-term sustainability (Kotsios, 2023). At the individual level, entrepreneurial resilience is commonly defined as the capacity to effectively adjust to challenges and setbacks (A. Masten, 2004) and to rapidly recover from adversity (Zautra et al., 2010). It involves processes of learning and strategic adaptation that enable entrepreneurs not only to persist but also to thrive amid uncertainty and disruptions (Ayala & Manzano, 2014; Fisher et al., 2016).

Despite its significance, the conceptualization of resilience remains fragmented and inconsistent across disciplines (Ungar, 2011; Van Der Vegt et al., 2015), with theoretical elaboration often overshadowing empirical clarity and applicability (Linnenluecke, 2017; Williams et al., 2017). This fragmentation has led to blurred conceptual boundaries with related constructs such as adaptability, transformability, and vulnerability (Korber & McNaughton, 2017). Consequently, operationalizing resilience remains challenging, particularly within entrepreneurship research, where clear definitions significantly inform both practice and policy (Hillman & Guenther, 2021).

Initially, resilience research in business focused predominantly on organizational resilience from systemic or evolutionary perspectives, emphasizing firms’ abilities to adapt and evolve over time (Duchek, 2020; Staw et al., 1981). More recently, scholarly attention has shifted to individual resilience among entrepreneurs and founders of micro and small enterprises, who frequently encounter multifaceted crises and persistent adversities (Ahmed et al., 2022; Bullough & Renko, 2013; Korber & McNaughton, 2017). Existing definitions underscore resilience as inherently context-sensitive, influenced by individual traits, cognitive and behavioral strategies, and broader institutional environments (Ahmed et al., 2022; Branicki et al., 2018; Ungar, 2011; Williams et al., 2017). Table 1 illustrates selected prominent definitions of resilience, highlighting this conceptual diversity.

Critically, while existing conceptualizations emphasize resilience’s contextual nature, they often overlook key dimensions related to gender and intersectionality. Entrepreneurship literature has historically treated entrepreneurs as a homogeneous group, implicitly neglecting how structural inequalities and intersecting social identities (such as gender, race, and socioeconomic status) shape resilience experiences and outcomes differently (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Carter & Marlow, 2007; Henry et al., 2016; Jennings & Brush, 2013). This gap aligns with broader psychological research, which argues that current measures of resilience are not gender-sensitive and typically result in women scoring lower due to neglect of how gender roles, social expectations, and environmental factors shape resilience differently across genders (Hirani et al., 2016). Consequently, important variations in how entrepreneurs experience and respond to adversity remain underexplored, limiting the conceptual and practical relevance of resilience frameworks.

Addressing these gaps is essential. Recognizing gender-specific dimensions, structural constraints, and intersectional identities can significantly enrich resilience theory, providing nuanced insights into entrepreneurial survival, growth, and sustainability. The following section, therefore, explicitly examines empirical evidence on gendered dimensions of entrepreneurial resilience. This exploration lays the groundwork for critically evaluating existing resilience frameworks and subsequently proposing a comprehensive gender-sensitive process-based resilience model.

Entrepreneurship and Gender

Entrepreneurship has traditionally been studied through lenses that largely overlook gender as a meaningful analytical dimension or significant construct (Henry et al., 2016; Jennings & Brush, 2013; Marlow, 2002). Welter (2011) pointed out that the methodologies in the literature revealed significant bias that understated the role and contribution of women in entrepreneurship. The dominant discourse in entrepreneurship research has characterized the field as meritocratic, gender-neutral, and equally accessible to all individuals willing to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities through a gender-agnostic approach, treating the entrepreneur as a universal figure, for example (Gartner, 1988; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Yet, empirical evidence consistently indicates that entrepreneurship is not a level playing field. Longitudinal data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reveal persistent gender disparities: although female participation in entrepreneurship increased globally, from a 6.1 percent share in startup activities between 2001 and 2005 to around 10.4 percent between 2021 and 2023 (GEM, 2024), substantial structural and cultural barriers continue to constrain women’s entrepreneurial potential significantly. For example, women are more likely than men to be solo entrepreneurs (1,47 women to 1 man) and disproportionately experience a higher fear of failure that inhibits their entrepreneurial activities and growth prospects (GEM, 2024). Also, women are far less represented among founders of potential high-growth firms (GEM, 2023).

Several interconnected factors contribute to these persistent gender disparities. A significant issue remains the enduring perception of entrepreneurship as fundamentally masculine (Bruni et al., 2004b). The image of entrepreneurs remains that of ‘heroic self-made men’ (Ahl, 2006), and entrepreneurial traits are stereotypically aligned with masculinity, being daring, decisive, aggressively competitive, and risk-tolerant (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Schumpeter, 1934/1983). Such androcentric norms have historically informed male-centric research approaches, implicitly casting women as “underperforming” entrepreneurs relative to an assumed male standard (Du Rietz & Henrekson, 2000). Gender expectations create double standards in evaluating women’s traits and decisions, with motional or relational strategies seen as weak, and assertiveness, valued in men, is penalized in women (Fine, 2010; Ridgeway, 2011). Scholars have long challenged these biases, arguing for a reframing of entrepreneurship theory to better account for women’s experiences and perspectives (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Calás et al., 2009). By casting women entrepreneurs as the “other” deviating from a male norm, this oversimplification implicitly attributes to them supposed deficiencies, limited ambition, higher risk-aversion, or lower growth-orientation, in comparison to male entrepreneurs (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Carter et al., 2003). As a result, women’s entrepreneurial achievements are often trivialized or framed as extensions of domestic roles (e.g., viewed as secondary to caregiving responsibilities), whereas similar actions by men are valorized as ambitious business strategies (Hughes et al., 2012; Marlow & McAdam, 2013). This reductionism also obscures the structural barriers confronting women entrepreneurs, such as discriminatory legal environments, gender-biased lending practices, restricted access to resources, and exclusion from influential networks (Bastian et al., 2023; Marlow & Patton, 2005). In addition, much of the literature has tended to homogenize “women entrepreneurs” as a monolithic category, treating gender in binary terms and overlooking differences among women (Marlow & Patton, 2005). Such approaches ignore the insights of intersectionality (K. W. Crenshaw, 2013), which recognize that factors like race, class, and culture intersect with gender to shape entrepreneurial experiences (Carter et al., 2015; Henry et al., 2016).

In recent years, the field has become more attuned to the diversity of women’s entrepreneurial experiences across different cultural and economic contexts (Badzaban et al., 2021; Essers & Benchop, 2009). Emerging scholarship shows that women engage in venture creation through varied, nuanced strategies, especially outside Western settings, as local conditions significantly shape their entrepreneurial opportunities and outcomes (Bastian et al., 2024; Ghouse et al., 2023; Henry et al., 2016; Ng et al., 2022; Shamieh & Althalathini, 2021; Tlaiss et al., 2024; Tlaiss & Kauser, 2019). For example, in conflict-affected Muslim-majority regions, women entrepreneurs have leveraged Islamic feminist values to challenge patriarchal norms and sustain their businesses amid war (Althalathini et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic notably exacerbated structural inequalities faced by women entrepreneurs, highlighting disproportionate burdens related to caregiving responsibilities, market segregation, and resource scarcity, significantly destabilizing women-led businesses (Afshan et al., 2021; Power, 2020).

Given these complexities, there is a growing call for more nuanced, gender-aware approaches in entrepreneurship research (Witmer, 2019). Feminist entrepreneurship scholars argue that the field’s traditional emphasis on financial growth and profit reflects a masculine-normative bias in defining success. This narrow focus neglects other crucial success criteria, such as an enterprise’s resilience in adversity, its long-term sustainability, and its social or community impact, which many women entrepreneurs prioritize in equal measure to, or even above, aggressive growth (Exposito et al., 2024; Henry et al., 2016; Jennings & Brush, 2013; Jones et al., 2025; Marlow & McAdam, 2013). In particular, adopting an intersectional lens is seen as crucial for accounting for the diverse identities and contexts of women entrepreneurs (Constantinidis et al., 2019; K. Crenshaw, 1989; Shields, 2008). Acknowledging the fundamental importance of gender in shaping entrepreneurial resilience, the following section explicitly explores empirical evidence concerning gendered differences in resilience outcomes within small business contexts, providing necessary groundwork to subsequently critically evaluate existing resilience frameworks.

Gendered Dimensions of Resilience in Small Businesses

Recognizing gender as a significant construct helps elucidate how resilience is differentially experienced and practiced by women entrepreneurs (relative to men) across three critical dimensions: business survival, financial management, and strategic adaptation. Indeed, emerging research demonstrates that resilience-building processes are highly contextual and gendered, validating the need to examine these dimensions through a gender lens (Bagheri et al., 2024). A clear understanding of these gender-specific dimensions sets the stage for evaluating existing resilience frameworks and proposing a more inclusive, gender-sensitive alternative.

Gender, Resilience, and Small Business Survival

In an era of continuous change, small and entrepreneurial companies must continuously adapt; resilience has thus become a critical capability for organizational survival and long-term sustainability (Liang & Cao, 2021). Organizational resilience encompasses proactive risk management (Burnard et al., 2018), effective resource mobilization (Hillman & Guenther, 2021), adaptability (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011), and the development of innovative capabilities to overcome adversity (Coutu, 2002; Duchek, 2020). Individual resilience, such as that of entrepreneurs and employees, further reinforces organizational resilience through creative problem-solving and effective coping strategies (Liang & Cao, 2021; Luthans, 2002). Personal factors, including family commitments and perceived opportunity costs, also shape entrepreneurs’ resilience and decisions about business continuity (Mahto et al., 2020). Indeed, the resilience of owners and founders is a critical determinant of small-firm survival and growth (Chadwick & Raver, 2020).

Women entrepreneurs, however, face additional challenges and systemic barriers to business survival that their male counterparts typically do not, such as discriminatory lending practices (Marlow & Patton, 2005), restrictive cultural norms (Bullough et al., 2022), exclusion from valuable business networks (Bastian et al., 2023), and widespread undervaluation of their enterprises by their stakeholders (Dutta & Mallick, 2023). To navigate these systemic barriers, women entrepreneurs frequently rely on relational resources and community networks to bolster resilience and sustain business operations (Bastian et al., 2023; Wood et al., 2021). In collectivist or marginalized contexts, women’s individual resilience is often deeply connected to broader community resilience, cultivated through mutual support networks offering emotional, informational, and practical assistance (Ng et al., 2022; Shelton & Lugo, 2021). Although close personal ties are sometimes viewed as inhibiting innovation (Bastian & Tucci, 2017), they serve as critical buffers for female entrepreneurs, especially in times of crisis, by bolstering resilience, psychological well-being, and business continuity (Bagheri et al., 2024; Ekinsmyth, 2011). Notably, empirical evidence from various academic studies suggests that women-owned businesses often exhibit resilience comparable to or even exceeding their male counterparts in terms of survival, particularly in specific industries or regions (Fairlie & Robb, 2009; Kalnins & Williams, 2014).

Gender, Resilience, and Financial Management

Another critical dimension of organizational resilience is financial management, which significantly influences a firm’s ability to withstand and respond effectively to financial shocks (Keskin et al., 2025; V. Lee et al., 2013; Prayag et al., 2018). This involves planned resilience, or the ability to prepare for different eventualities, as well as adaptive resilience, the ability to respond to emerging challenges (V. Lee et al., 2013; Nilakant et al., 2013). Orchiston et al. (2016) refer to ‘planning and organizational culture’ and a firm’s ‘collaboration abilities and innovativeness’ that allow firms to better manage resources, sustain operations, and maintain competitiveness during crises. Other factors that impact the financial performance of firms are problem-solving abilities and strong external linkages with stakeholders (identified as key sustainable leadership practices by Avery & Bergsteiner (2011) and entrepreneurial level resourcefulness (Ayala & Manzano, 2014). Small firms that adopt such practices can adjust their strategies to preserve revenue streams and sustain competitiveness during market disruptions (Gorjian-Khanzad & Gooyabadi, 2021; Gunasekaran et al., 2011).

However, women entrepreneurs typically face pronounced gender-specific barriers in accessing formal financing, leading them to rely heavily on informal financial resources. These include personal savings, family support, and informal community-based funding mechanisms (C. G. Brush et al., 2006; Malmström & Wincent, 2018). During major economic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, these financing gaps have been exacerbated, underscoring the necessity for proactive financial planning (e.g., maintaining emergency funds or insurance schemes) to uphold resilience and sustainable growth (Sharma & Rai, 2023). Despite systemic underinvestment in women-led firms, empirical studies highlight women’s disciplined fiscal management (Muravyev et al., 2009), strategic debt control, and effective use of financial resources (Ghosh et al., 2018). Such cautious financial practices serve as key resilience strategies, enabling women entrepreneurs to maintain financial autonomy and stability even in resource-constrained, male-dominated business environments (C. G. Brush et al., 2006). Women entrepreneurs frequently demonstrate strong financial resilience, exemplified by their consistent record of higher loan repayment rates compared to their male counterparts in microfinance settings (D’Espallier et al., 2011). Additionally, research on small businesses indicates that women-led firms typically engage in more conservative financial management practices, such as lower levels of debt financing and careful risk mitigation strategies (Watson & Robinson, 2003). These disciplined fiscal behaviors are key resilience strategies that enable women entrepreneurs to effectively manage economic shocks and maintain business stability.

Gender, Resilience, and Strategic Adaptation

Strategic adaptation, the capacity to effectively respond and adapt to changes in the business environment, is integral to organizational resilience, particularly for small enterprises vulnerable to external disruptions (Schindehutte & Morris, 2001; Shepherd, 2003; Shepherd & Williams, 2014). Adaptive resilience involves strategic initiatives such as sensing market opportunities (Orchiston et al., 2016), proactively reconfiguring resources (Chaudhary et al., 2024), entering new markets, and integrating technological innovations to sustain competitiveness (Schindehutte & Morris, 2001; Sheffi, 2005). Strategic adaptation involves proactively adjusting business strategies to respond effectively to environmental uncertainties, disruptions, and challenges, a process influenced significantly by entrepreneurs’ confidence levels and their strategic use of business planning tools (Bullock & Aghaey, 2024), as well as by their capacity to adapt business models and resource strategies during crises, such as observed among rural small businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hutchinson et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, gender-specific constraints significantly shape the strategic adaptation processes of women entrepreneurs. Socio-cultural role expectations (Ahl & Marlow, 2012), disproportionate domestic caregiving responsibilities (Jennings & McDougald, 2007), and limited institutional support networks lead women-led businesses toward cautious, incremental strategic adaptations rather than high-risk transformations (Bagheri et al., 2024; Kappal & Rastogi, 2020). Women entrepreneurs frequently rely on diplomatic negotiation, stakeholder collaboration, incremental innovation (Manolova et al., 2020), and relational resourcefulness (Bastian et al., 2023) to manage pressures and adapt effectively without jeopardizing stability. These strategic resilience practices, characterized by relational trust and community engagement, enable women-owned businesses to balance competing demands and pursue sustainable growth (Barrachina-Fernández et al., 2021; Shelton & Lugo, 2021).

Critique of Existing Resilience Frameworks

As established in the preceding section, resilience manifests differently in small businesses depending upon gender-specific conditions, structural constraints, and adaptive strategies. However, mainstream entrepreneurship literature traditionally employs resilience frameworks that often fail to account for these critical gendered dimensions. The following section critically examines existing resilience frameworks, namely, trait-based, cognitive-behavioral, and process-based, to evaluate how each addresses gender-specific dimensions, and then moves on to propose a more inclusive, gender-sensitive framework of entrepreneurial resilience.

Trait-Based Framework

The trait-based framework conceptualizes resilience predominantly as an intrinsic set of personal qualities or traits, such as optimism and emotional regulation (Kendler et al., 2003; Segerstrom et al., 1998), risk tolerance (Stewart & Roth, 2001), self-efficacy, personal drive and sense of accountability (Hedner et al., 2011), and grit (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) and hardiness (Kobasa, 1979), that equip individuals to overcome adversity and recover from setbacks (De Vries & Shields, 2006; Hmieleski et al., 2015; Kotsios, 2023). This model, widely adopted in psychology and entrepreneurship literature, aligns with the notion that successful entrepreneurs possess a distinct personality profile, combining technical competencies with soft skills that support autonomous and strategic action (Moss & Tilly, 1996; Weber et al., 2011).

However, significant gender-related limitations exist within the trait-based perspective. To begin with, debates persist over whether resilience-related traits are innate or acquired. While studies have shown genetic components to optimism and emotional regulation (Kendler et al., 2003; Segerstrom et al., 1998), others emphasize environmental influences such as familial support and exposure to adversity as critical in shaping these traits (A. S. Masten & Reed, 2002; Southwick et al., 2014). The fluidity of such traits raises concerns about the validity of trait-based models that rely heavily on cross-sectional data, potentially overlooking resilience as a developmental trajectory (Smith et al., 2008). In addition, traits commonly valorized, such as autonomy, assertiveness, risk-taking, competitiveness, and emotional detachment, are historically and culturally associated with masculine entrepreneurial ideals (Branicki et al., 2018; Powell & Eddleston, 2013). This implicit masculine bias reinforces the previously discussed normative image of entrepreneurs as predominantly male, white, and individualistic, marginalizing or overlooking relational forms of resilience frequently demonstrated by women entrepreneurs (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Bruni et al., 2004a). For instance, relational resilience strategies involving emotional intelligence, empathy, and community support, crucial for women-led businesses, are undervalued or misinterpreted as indicative of deficiency rather than legitimate resilience capacities (J. Lee & Wang, 2017; Lewis, 2006; Torres et al., 2019). Moreover, trait-based approaches abstract resilience from contextual factors, including structural inequalities and socio-economic conditions that significantly shape women’s entrepreneurial experiences (Branicki et al., 2018; Ishak & Williams, 2018). It also neglects the intersectional pathways by which gendered traits are socially constructed and interpreted differently for women entrepreneurs, thus perpetuating systemic biases and interpretive asymmetries (Ahl, 2006; Powell & Eddleston, 2013).

Cognitive-Behavioral Framework

The cognitive-behavioral framework conceptualizes resilience as adaptive cognitive strategies and behavioral practices employed by entrepreneurs in response to adversity, such as goal-setting, emotional regulation, cognitive reframing, adaptive decision-making, and strategic resource mobilization to sustain and recover business operations (Franczak & Weinzimmer, 2022; S. E. Hobfoll, 1989; Shepherd & Williams, 2014; Williams et al., 2017). Conservation of Resources (COR) theory underpins this approach, emphasizing that entrepreneurs strategically protect and replenish critical resources, facilitating adaptive behaviors that enable resilience during crisis situations (Egozi Farkash et al., 2022; S. Hobfoll et al., 2015). Empirical evidence further supports this by demonstrating that entrepreneurs’ confidence levels and systematic use of business planning significantly impact their adaptive behaviors, influencing the extent and effectiveness of their resource mobilization during periods of adversity (Bullock & Aghaey, 2024).

Yet, cognitive-behavioral frameworks also demonstrate significant gender-related shortcomings by placing considerable emphasis on autonomous, assertive, self-regulating behaviors historically aligned with masculine-coded ideals of entrepreneurship (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Bruni et al., 2004b). Consequently, the relational, emotional, or community-centered adaptive behaviors frequently practiced by women entrepreneurs are overlooked or misinterpreted as less resilient or even counterproductive (Lewis, 2006; Marlow & McAdam, 2013). For example, behaviors such as collaborative negotiation, emotional expression, and mutual support, central to women entrepreneurs’ adaptive resilience strategies, are often undervalued within cognitive-behavioral frameworks (Bagheri et al., 2024; Shelton & Lugo, 2021). Additionally, the cognitive-behavioral approach tends to neglect structural contexts and resource inequalities that profoundly shape how resilience is enacted and expressed differently among women entrepreneurs (Ahl, 2006; Marlow & Patton, 2005). This oversight obscures the reality that women often face unequal access to critical entrepreneurial resources (financial, informational, institutional), thus constraining their strategic adaptive capacities and significantly influencing the types of resilience behaviors they can realistically deploy (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Powell & Eddleston, 2013).

Process-Based Framework

The process-based framework conceptualizes resilience as a dynamic, context-sensitive trajectory involving iterative processes of learning, sense-making, identity development, and strategic adaptation over time (Ahmed et al., 2022; Bernard & Barbosa, 2016; Fisher et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2023). Unlike trait-based or cognitive-behavioral approaches, it explicitly integrates temporality, social embeddedness, and adaptability into resilience conceptualization, recognizing resilience as continuously shaped by relational engagements, organizational experiences, and socio-economic conditions (Ahmed et al., 2022; Walsh, 2003). The process-based perspective considers resilience to be a socially and contextually embedded trajectory involving disruption, adaptation, and eventual transformation (Gonzalez-Lopez et al., 2019; Shepherd et al., 2020).

Despite this inclusive and dynamic orientation, the process-based approach to entrepreneurship remains relatively limited regarding explicit gendered analysis. While well-suited for capturing gendered entrepreneurial experiences due to its emphasis on relational and contextual dynamics, empirical applications to gender-specific resilience contexts in entrepreneurship remain nascent and underdeveloped (Carter & Marlow, 2007; Constantinidis et al., 2019; Shields, 2008). Recent research calls for a multidimensional view of resilience that explicitly addresses how gender intersects with conflict, socio-economic conditions, and power structures, recognizing resilience as a complex interplay of structural, relational, and individual factors (Juncos & Bourbeau, 2022). As it stands, the process-based model still requires further integration of intersectional analyses to fully capture how gender interacts dynamically with race, class, ethnicity, and other identity markers to shape entrepreneurial resilience trajectories uniquely (Carter & Marlow, 2007; Constantinidis et al., 2019). While the framework already allows for nuanced recognition of women’s relational resilience strategies and context-dependent adaptability, existing applications of this approach within entrepreneurship have yet to sufficiently articulate or explicitly address the structural and intersectional barriers frequently confronting women entrepreneurs (Ungar, 2013; Walsh, 2003). Thus, significant potential remains untapped for developing a more explicitly gender-sensitive and intersectionally aware process-based resilience framework within entrepreneurship studies.

This critical evaluation of existing resilience frameworks reveals significant limitations, especially concerning the nuanced, gendered entrepreneurial contexts highlighted earlier. Specifically, the predominant frameworks either implicitly reinforce masculine-coded ideals (trait-based and cognitive-behavioral frameworks) or have yet to fully exploit their inclusive potential through explicit gendered and intersectional analyses (process-based framework). Recognizing these critical gaps, this study suggests a more comprehensive, explicitly gender-sensitive resilience model, integrating the strengths of the process-based approach with detailed attention to gender-specific contexts, structural barriers, coping mechanisms, and intersectional dimensions.

Towards a Gendered Model of Resilience

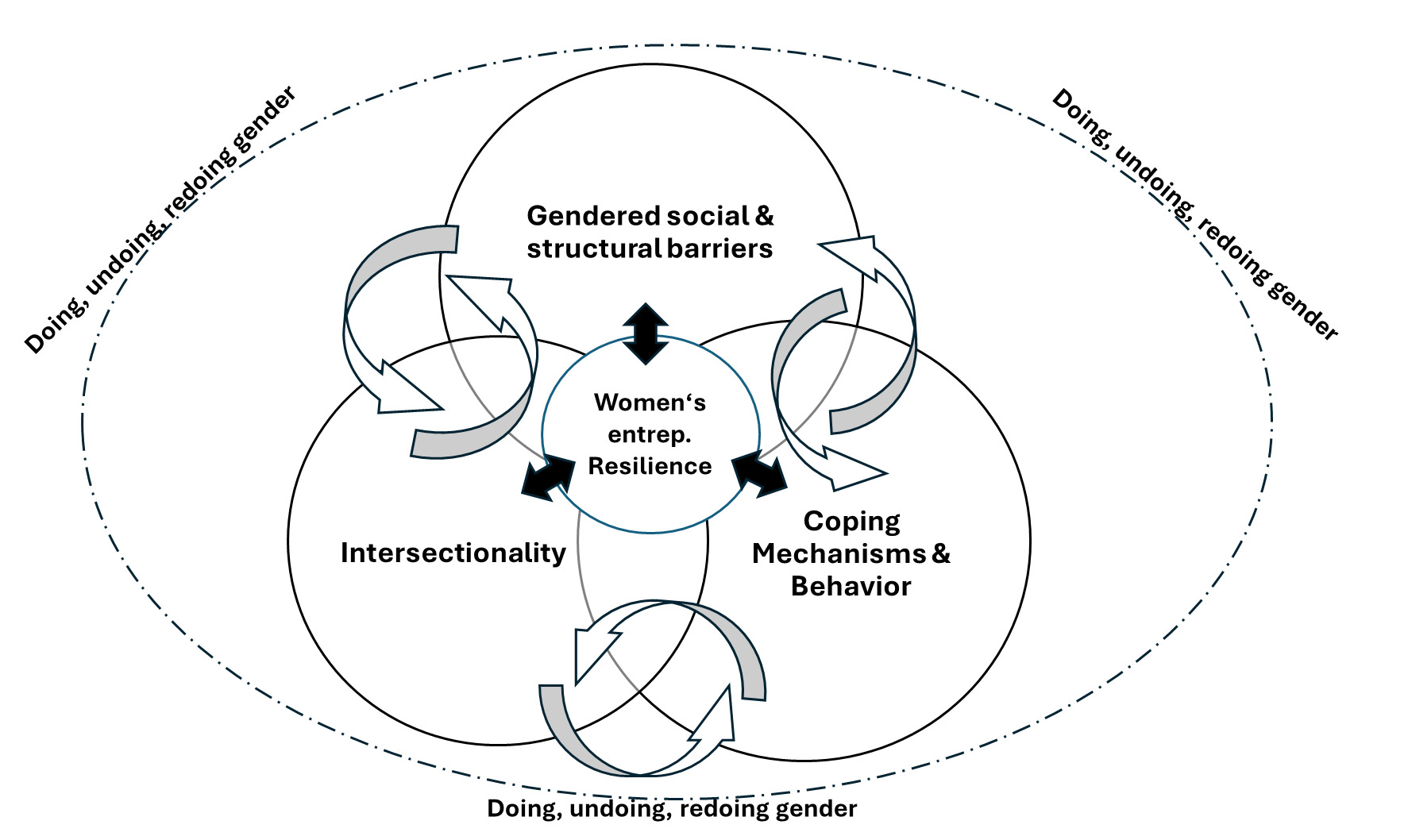

Integrating gender into resilience research requires recognizing how women perform, challenge, or redefine gender norms in their strategies-known as doing, undoing, and redoing gender (Butler, 1990; Deutsch, 2007; Rao et al., 2021; West & Zimmerman, 1987). Women may adhere to, challenge, or reshape gender norms depending on context, barriers, and intersectional challenges (C. Brush et al., 2009; Martin, 2006; Rao et al., 2021). Addressing these identified gaps, this study suggests a gender-sensitive, process-based model that emphasizes three interrelated dimensions: gendered coping mechanisms, structural barriers, and intersectionality.

Coping Mechanisms: Gendered Differences and Practices

Coping mechanisms significantly shape entrepreneurs’ responses to adversity, reflecting embedded gendered norms and social expectations (Eagly & Wood, 2012; Ghouse et al., 2023; Tlaiss & Kauser, 2019). As demonstrated, male entrepreneurs predominantly employ problem-focused coping, involving proactive problem-solving, assertiveness, and autonomy, aligning with historically masculine entrepreneurial ideals of control and competitiveness (Ayala & Manzano, 2014; Bullough et al., 2022). In contrast, women entrepreneurs more frequently adopt emotion-focused coping, emphasizing relational resources, emotional regulation, and community-based support, consistent with gendered expectations of relationality and interconnectedness (C. Brush et al., 2009; Lewis, 2006; Matud, 2004). Additionally, women in male-dominated contexts often integrate both relational and instrumental resilience strategies, explicitly designed to overcome gender-specific occupational barriers and foster greater gender inclusion (Bridges et al., 2023). Although traditionally undervalued (C. Brush et al., 2009; Lewis, 2006), these relational coping practices are particularly evident in family-owned enterprises, where gendered roles and interpersonal dynamics distinctly shape resilience strategies. Recent gender-sensitive scholarship increasingly recognizes such relational approaches as legitimate and essential to the adaptability and sustainability of women-owned businesses (Bullough et al., 2022; Shelton & Lugo, 2021). Consequently, a gender-sensitive, process-based resilience model must explicitly integrate these diverse coping mechanisms, ranging from collaborative networks and mentoring relationships to emotional support systems and community solidarity, recognizing their fundamental role in resilience processes (Windle et al., 2011).

Structural Barriers: Gendered Contexts and Constraints

Structural barriers, both formal (legal, policy-level) and informal (cultural, institutional), critically shape women entrepreneurs’ capacity to develop and enact resilience (Coulomb, 1999; Jennings & Brush, 2013; Panda, 2018; Shamieh & Althalathini, 2021). Formal institutional constraints, such as discriminatory laws or policies restricting women’s access to financing, capital, and property ownership, significantly hinder their resource mobilization capabilities (OECD, 2022; World Bank, 2023). When women entrepreneurs cannot freely acquire capital or own property, they have fewer resources to buffer their ventures against adversity or market disruptions, limiting their adaptive resilience during crises (Shamieh & Gergess, 2024; Tlaiss et al., 2024). Even without explicit legal barriers, informal constraints persist through deeply ingrained cultural expectations and gender stereotypes, further marginalizing women’s entrepreneurial legitimacy and restricting their access to critical resources and networks (Powell & Eddleston, 2013; Shelton, 2006). For instance, gendered caregiving expectations place disproportionate family responsibilities on women entrepreneurs, significantly reducing the time and energy available for business activities, thus constraining their capacity to build resilience (Jennings & McDougald, 2007). Implicit biases within entrepreneurial ecosystems, such as skepticism towards women’s leadership or exclusion from male-dominated networks, further undermine women’s opportunities to acquire mentorship, funding, and market knowledge essential to responding resiliently to challenges (Bastian et al., 2023; Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Thus, a gender-sensitive resilience framework must explicitly recognize that entrepreneurial resilience emerges not solely from individual traits or isolated responses, but from dynamic interactions within a gendered institutional and cultural context (Henry et al., 2016).

Intersectionality: Recognizing Diverse Entrepreneurial Realities

As highlighted earlier, adopting an intersectional lens is crucial for understanding the diverse realities and multiple social identities of women entrepreneurs (K. Crenshaw, 1989; A. Masten, 2001; Shields, 2008). This perspective acknowledges that “women entrepreneurs” are not a homogeneous category; each individual’s resilience trajectory is uniquely shaped by the intersection of gender with her other social identities and structural conditions (Carter & Marlow, 2007). Intersecting dimensions such as race, class, and culture create varied forms of inequality and oppression (Risman, 2004; Shields, 2008), compounding the vulnerabilities that impede women’s resilience more than men’s (Vinyeta et al., 2015). Therefore, any gender-sensitive resilience analysis must account for how factors like ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and family roles interact with gender to produce distinct entrepreneurial challenges and adaptive responses.

Applying an intersectional perspective reveals that the barriers and resilience strategies of women entrepreneurs vary significantly across different social locations (Amine & Staub, 2009; Constantinidis et al., 2019). For instance, ethnic minority women or those from economically disadvantaged communities often face compounded discrimination: gender bias intertwined with racial or class-based inequalities intensifies the hurdles to venture creation and growth. Such overlapping disadvantages necessitate context-specific resilience practices. Constantinidis et al. (2019) illustrate that in Morocco, family expectations and cultural norms, in combination with gender, shape women business owners’ coping mechanisms and success strategies. Likewise, Amine and Staub (2009) document that in sub-Saharan Africa, women entrepreneurs confront a daunting array of structural challenges, spanning socio-cultural, economic, and legal barriers, which demand tailored resilience responses. Al-Dajani and Marlow (2010) further show that Jordanian home-based microentrepreneurs must carefully negotiate their right to self-employment within household hierarchies, balancing entrepreneurial ambitions with subordinate familial roles. These diverse cases reinforce earlier observations that women in many contexts are often required to “bounce back” more frequently from setbacks such as discrimination, disproportionate caregiving responsibilities, and market exclusion.

Synthesizing the above insights, this study presents a novel comprehensive model of entrepreneurial resilience that, to our knowledge, is the first framework to systematically integrate gendered coping strategies, structural contexts, and intersectional identity factors. This gender-sensitive, process-based framework reconceptualizes resilience as a dynamic, contextually embedded process rather than a static individual trait (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Henry et al., 2016; Jennings & Brush, 2013). By explicitly challenging the masculine biases of prior resilience models, which often privileged individualistic, masculine-coded behaviors, this suggested model legitimizes relational and community-oriented coping mechanisms that have long been undervalued in mainstream entrepreneurship research (Bruni et al., 2004a; C. Brush et al., 2009). The model also foregrounds structural and institutional barriers as central to resilience, addressing contextual constraints that earlier frameworks often overlooked (Duchek, 2020; Korber & McNaughton, 2017). Finally, an intersectional lens is built into the framework, acknowledging that gender interplays with race, class, and other identities to shape diverse resilience trajectories (Constantinidis et al., 2019; K. Crenshaw, 1989; K. W. Crenshaw, 2013). In uniting these dimensions, our model addresses a critical gap in the literature (Ahmed et al., 2022) and significantly advances the theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial resilience while providing a foundation for more inclusive, gender-responsive interventions.

Implications and Future Research

The suggested gender-sensitive resilience model yields important implications for both entrepreneurship practice and policy, alongside clear directions for future research. From a policy and practical perspective, the findings suggest that support programs should incorporate gender-aware resilience training that embraces relational strategies common among women entrepreneurs (e.g., community-building, mentoring, and networking) (Bagheri et al., 2024; C. Brush et al., 2009). Addressing structural barriers through inclusive institutional reforms is equally critical: policymakers need to remove discriminatory obstacles and ensure equitable access to financial services, legal rights, and supportive infrastructure (such as affordable childcare and safe transportation) to bolster women’s resilience (Choi, 2024; OECD, 2022). Facilitating women-focused mentoring and networking platforms can further strengthen relational and intersectional resilience by fostering knowledge exchange, emotional support, and resource sharing tailored to women’s entrepreneurial contexts (Bastian et al., 2023; Shelton & Lugo, 2021).

Policies must also adopt an intersectional lens, explicitly accounting for how overlapping identities (gender, race, class, etc.) compound the challenges faced by diverse women entrepreneurs (Constantinidis et al., 2019; K. Crenshaw, 1989). In addition, rethinking success metrics to value long-term sustainability, community impact, and incremental innovation, rather than narrowly emphasizing rapid growth or market dominance, will better align policy and evaluation frameworks with the realities and values of women-led ventures (Exposito et al., 2024; Henry et al., 2016). Finally, continuous learning and adaptation should be built into resilience programs: ongoing monitoring and iterative evaluation of gender-focused initiatives ensure that support remains responsive to women entrepreneurs’ evolving needs and changing contexts (Ryan, 2022). Collectively, these measures offer practical guidance for stakeholders aiming to foster a more inclusive and equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem.

From a research perspective, this study opens several avenues for further inquiry to refine and validate the proposed model. Future research should empirically test this gender-sensitive resilience framework across diverse contexts, different industries, cultural settings, and regions (including under-studied Global South environments), to assess its generalizability and nuance. For instance, longitudinal studies could track how women entrepreneurs’ resilience capacities develop and change over time under varying personal and institutional conditions. Powell and Eddleston’s (2013) findings that family-to-business support benefits women entrepreneurs but not men underscore the value of examining how gendered responsibilities and resources influence resilience trajectories. Expanding research beyond Western, individualistic settings is also crucial: resilience in collectivist or resource-constrained communities may manifest through alternative processes, calling for engagement with decolonial and indigenous perspectives on entrepreneurship (Amo-Agyemang, 2021; Bastian et al., 2023). Additionally, deeper intersectional analyses are needed to explore how gender intersects with race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and age in shaping entrepreneurial resilience. Such studies will not only empirically substantiate the model but also ensure it is robust, culturally inclusive, and attuned to the complex reality of women entrepreneurs globally.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to entrepreneurship research by bridging a critical gap: it integrates gender and intersectionality into the understanding of entrepreneurial resilience (Ahl & Marlow, 2012; Calás et al., 2009). This research demonstrated that prevailing resilience frameworks, whether emphasizing traits, cognitive-behavioral skills, or dynamic processes, have historically overlooked the distinct experiences and strategies of women entrepreneurs (Ahmed et al., 2022; Branicki et al., 2018; Smyth & Sweetman, 2015). It thereby moves beyond treating entrepreneurs as a homogeneous group, foregrounding how gender and other intersecting identities shape resilience in distinct ways (Ahl, 2006; K. Crenshaw, 1989; Jennings & Brush, 2013). By synthesizing evidence on gendered coping mechanisms, structural constraints, and identity factors, this research proposed a comprehensive process-based resilience model that more accurately reflects women business owners’ realities, including relational and community-oriented resilience practices often overlooked in mainstream approaches (Bastian et al., 2023; Ng et al., 2022). This gender-sensitive framework challenges traditional, masculine-biased assumptions (Lewis, 2006) and significantly extends existing theory, offering a more inclusive lens for analyzing how entrepreneurs navigate adversity.

The significance of the suggested model lies in its potential to enhance both scholarship and practice. These contributions come at a pivotal time: as women’s participation in entrepreneurship continues to expand globally, integrating a gender-sensitive lens is increasingly essential to understanding and supporting entrepreneurial resilience (GEM, 2024). It provides researchers with a nuanced conceptual foundation to better analyze resilience in entrepreneurial settings, and it offers practitioners and policymakers insight into designing support systems that acknowledge gender-specific needs (Carter et al., 2015). This research acknowledges that our suggested model is presently conceptual; like any new theoretical framework, it requires empirical validation and refinement. This limitation notwithstanding, the framework catalyzes reimagining resilience in entrepreneurship, prompting both scholars and practitioners to reconsider how resilience is defined and nurtured across diverse entrepreneurial contexts. By adopting a gender-informed and intersectionally aware approach, future studies and policies can foster more equitable and effective pathways for entrepreneurs to withstand and grow from challenges. Ultimately, embracing this inclusive resilience perspective is not only academically enriching but also a vital step toward building a more inclusive and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem (De Bruin et al., 2007).