Introduction

Scholars have long noted that there is a difference between men and women when it comes to entrepreneurial behavior. This has been a common finding over the years and different contexts. As such, this has been much fodder for research and the resulting policy changes. However, despite this level of attention, the same issues that existed in the 1980s continue to exist today, namely a perceived difference between men and women in entrepreneurial propensity. For example, reflecting on their research on gender and entrepreneurship in the early 1980’s, Holmquist and Sundin (2020) described women entrepreneurs as a phenomenon at the intersection between a “women’s world” and the “world of entrepreneurship” rather than true integration. They view this description as still valid today, postulating this intersection has been, and still is, constructed as a research field of its own, gender and entrepreneurship. This research field is connected to and relies heavily on the two fields that it combines, gender studies and entrepreneurship studies.

However, research does an incomplete job of combining them into a coherent synthesis. The authors postulate that part of the reason why this synthesis is incomplete is a lack of understanding between the two fields as well as competing epistemologies. For example, Holmquist and Sundin (2020) rationalize that the recent “theoretical turn” has made entrepreneurship and empirical work even less visible in gender research to the point where entrepreneurship scholars do not pay heed to feminist insights uncovered in gender research. In a similar vein, Ward et al. (2019) agree that the subcategory of gender and entrepreneurship, while having gained traction in the last two decades, has appeared to suffer from an identity crisis, neither finding a home within entrepreneurship nor within gender studies as both fields did not value what the other can teach and/or offer each other (Aguinaga et al., 2013; Mazzarol et al., 1999).

This lack of understanding resulted in gender being “added” to entrepreneurship research, and entrepreneurship being “added” to gender research, and subsequently, gender and entrepreneurship studies has not been integrated into either field fully (Holmquist & Sundin, 2020). This lack of epistemological understanding is not uncommon as different fields struggle to effectively interact with each other due to differences in viewpoint and methodology. For example, scholars have struggled to understand the relationship between corporate social responsibility and economics due to the different assumptions of management and economics (Muldoon et al., 2022). Or, in strategy, the difference between external versus internal factors driving a firm’s performance (Hoskisson et al., 1999). To this end, the authors offer a literature review that synthesizes these two different streams of research in order to uncover themes that may allow the two fields to intersect, communicate and mutually benefit in future research undertaken under gender and entrepreneurship.

The authors’ contention that this lack of communication is a reason why these two fields have not created a coherent synthesis and these issues are foundational. Like other fields, the early fundamentals continue to impact the present-day research being conducted on gender and entrepreneurship insofar as the mainstream agenda in both fields fails to acknowledge the possibility of a richer understanding of the phenomenon of women’s entrepreneurship, in terms of understanding the functioning of entrepreneurship, as well as understanding how women form their working lives (Holmquist & Sundin, 2020; Richard et al., 2021). As noted earlier, Ahl and Marlow (2021) believe that today’s mainstream research on women entrepreneurship remains set in a male–female comparative frame, where women are seen to be on the losing side. Even more discouraging, Yousafzai et al. (2019) suggest that women, as a category, have fewer, smaller, and less profitable businesses leading to suggestions of gender-related under-performance. The assumption of entrepreneurship as something male is prevalent in measuring instruments comparing men and women (Mirchandani, 1999; Muldoon et al., 2019; Robb & Watson, 2012).

To expand, women are assessed as to whether they measure up to the male norm, and if not, they are advised to improve themselves through business courses, increasing their management skills, boosting their self-confidence, networking better, et cetera (Ahl & Nelson, 2014; Foss et al., 2018). If this sounds familiar it is because it is, bringing the research right back to the very first study done by Schwartz in 1976! This reflects the postfeminist sensibilities of self-surveillance, self-discipline, and a makeover paradigm, and as noted by Marlow (2013), it effectively introduces a blame discourse where women are held responsible for their alleged shortcomings while structures are not (Ahl & Marlow, 2021).

The lack of attention and responsibility given to structures surrounding women, while instead focusing the blame on women themselves, is exactly the gap that needs to be explored, unpacked and checked for accuracy. Based on this examination, the authors argue that it is the system or the entrepreneurship ecosystem, not the individual, that perpetuates discrimination and biases in entrepreneurship participation. A second theme is that we need different methods. Although quantitative research is useful in providing snapshot guideposts of directional trends, the authors maintain that the methodological approaches taken to arrive at these conclusions do not tell the whole story. For example, using feminist theory, Marlow (2020) found research has evolved from assumptions that men are naturally entrepreneurial and can provide leadership to women to a more critical, embedded reflection. While the authors challenge that these findings again may be contextually dependent and are bold in their assertions, the authors appreciate the nuanced approach of exploring postfeminism from a critical perspective.

Literature Review

To construct this conceptual synthesis, we employed an integrative, narrative review strategy that balances breadth with thematic depth. First, we ran systematic keyword searches (“gender AND entrepreneurship”, “women entrepreneurs”, “feminist theory”, “entrepreneurship policy”) in Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar, capturing peer-reviewed work published 1976-2024, a window that spans the earliest feminist critiques of entrepreneurship to current ecosystem debates. Reference-chaining of seminal studies (e.g., Holmquist & Sundin, 1988) ensured classic contributions were retained even if they pre-date database indexing. Only English-language sources that explicitly addressed gender, feminism or women in entrepreneurial contexts were included, while dissertations and opinion pieces were excluded to maintain scholarly rigour. Guided by feminist empiricism, postfeminism and poststructural feminism, we conducted iterative coding to surface cross-cutting themes and identify gaps, an approach consistent with prior reviews in gender-entrepreneurship research (Cardella et al., 2020). The resulting thematic map anchors the discussion that follows and is consistent with established guidelines for integrative, narrative reviews (Snyder, 2019; Torraco, 2016).

An examination of the literature reveals a marked difference between the two literatures. For example, researchers of the 1990’s note that entrepreneurship scholarship efforts focused on quantifying performance, counting how many self-employed and small firm owners existed, exploring how these numbers can be increased and how these business owners can be encouraged to grow their ventures (Greene & Patel, 2013). This focus on economic outcomes came largely due to its audience, academics, business advisors, practitioners, and subjects of research, being overwhelmingly male (Marlow, 2020).

It was not until the late 1990’s that a distinct critique gained traction, recognizing the negative impact of social constructions of gender, specifically femininity and its dissonance with preferred entrepreneurial characteristics (Marlow, 2020). It was thought that such change could be achieved by supporting, advising, and training women to adopt a more masculine entrepreneurial attitude, becoming more agentic, more risk tolerant, competitive, and self-confident, resulting in higher levels of success of women in entrepreneurial pursuits (Small Business Service, 2003). However, the approach “by men, about men and for men” now stood as “women should be men,” which was required as being retrograde.

As such, this was met with a flurry of arguments and the ensuing academic critiques (Ahl, 2006; Bruni et al., 2005), dismissing the notion that “if only women were more like men” (Marlow, 2013, p. 10) then their persistent under-representation as entrepreneurs, and the underperformance of their ventures, would be solved. A discourse analysis of women and entrepreneurship research conducted by Ahl (2006) argued that the construction of the woman entrepreneur as secondary to her male peer results from normative masculinized assumptions prevalent in mainstream entrepreneurship research. The five discourses identified include: the primary purpose of entrepreneurship is profit on the business level and economic growth on the societal level; that entrepreneurship is something male; that entrepreneurship is an individual undertaking; men and women are different; and finally, that work and family are separate spheres where women prioritize, or ought to prioritize, their family (Ahl, 2006).

The authors believe that these five discourses may not be contextually relevant across all cultures and geographies. To demonstrate, Gupta and Fernandez (2009) examined the similarities and differences in characteristics attributed to entrepreneurs across cultures, challenging the view that some scholars have in recognizing that there is a widespread ethnocentric bias in extant entrepreneurship research that treats the definition of entrepreneurship as universal which limits the scholarly understanding of characteristics and attributes ascribed to entrepreneurs in different countries. Welter et al. (2019) position the need for contextualized research somewhat differently. They highlight that entrepreneurship researchers have moved from challenging the “standard” or Silicon Valley model of entrepreneurship towards considering more subjective elements and the construction and enactment of contexts and now are challenging the theorization of entrepreneurship by broadening the contextual elements that beg for examination and demand theoretical development (Welter et al., 2019). Although the employment of quantitative methodology is important, there was a growing unease that the numbers may not tell the whole story. For instance, Perren and Jennings (2005) observed that social discrimination did not receive adequate attention in the literature due to a myopic fascination with profit and productivity. When issues such as inequality and exclusion were acknowledged, whether as gender, ethnicity or class, the focus was on identifying pathways to encourage under-represented or disadvantaged groups into entrepreneurship.

The focus on productivity, at the expense of other topics (e.g., quality of life), occurred, as Holmquist and Sundin (2020) postulated that the field of entrepreneurship borrowed from the method and assumptions of neoclassical economics with its focus on productivity and quantitative studies. This approach has several limitations. Namely, a lot of entrepreneurship is not productive in terms of increasing society’s wealth; however, this entrepreneurship is important because it may support an individual or family when full-time employment cannot address their needs for whatever reason. Likewise, another common criticism of neoclassical economics is that it is undersocialized with little consideration to social relationships.

In gender studies, however, they observe the opposite trend, with more qualitative studies being deployed in the direction of a philosophical theory. However, this approach also became limited. As women, as individuals of flesh and blood, no longer exist and instead, intersectionality, not gender, is now emphasized (Holmquist & Sundin, 2020). These issues, both in gender and entrepreneurial studies, created an understanding that entrepreneurship researchers should focus on generating domain-specific theories for the field, with empirical studies that use quantitative, as well as qualitative methods, and that account for differences in contexts (Holmquist & Sundin, 2020). Despite these claims, the combination of both fields have emerged. A systematic review of over 2800 peer reviewed journal articles on gender and entrepreneurship from 1950 to 2019 concluded that it is a multidisciplinary field that saw expansive growth from 2006 onwards (Cardella et al., 2020). The results suggest that the interest of academics, who have approached the study of gender and entrepreneurship, has fundamentally converged into two major areas of research: the study of barriers (economic, political, and social) and the relationship between socio-cultural factors and the gender-gap.

Decades of scholarship converge on a common critique: women’s entrepreneurial activity is routinely evaluated against a male benchmark, positioning men’s ventures, risk preferences and growth trajectories as the unexamined standard. Early observers labelled the field “by men, about men and for men” (Holmquist & Sundin, 1988) and subsequent analyses show how positivist, individual-level metrics obscure the structural drivers of gendered outcomes (Ahl, 2006). Framing research as a deficit comparison sustains a narrative in which women must “fix” themselves through training or confidence-building, while the gendered institutions that shape opportunity remain unchallenged (Ahl & Nelson, 2014; Foss et al., 2018). Recognizing this bias is therefore a pre-condition for re-orienting inquiry toward ecosystem-level change rather than individual remediation.

Research on Entrepreneurship Policy

The field of entrepreneurship policy grew in the late 20th century as an offshoot of the more established small business policy (Gilbert et al., 2004). It was born of the realization by politicians that small business policy measures aimed at impacting the conditions for established small businesses was not the same as measures aimed at creating new entrepreneurial ventures and new economic activity (Audretsch, 2007). Unlike small business policy, entrepreneurship policy focuses on the early stages of business life: pre-launch, launch and typically the 12 months following launch (Gilbert et al., 2004). Early entrepreneurship policy in Western countries was geared toward funding the promotion of entrepreneurial activity, specifically to improve the information and advisory system, start entrepreneurship courses, affect the education system through the inclusion of entrepreneurship pedagogy and improving access to finance for entrepreneurs (Audretsch, 2007). Policies typically take the form of government support for business start-ups and the ease in which starting and operating a business is in a particular region (World Economic Forum, 2013).

The primary measurement of entrepreneurship policy impact was the number of new businesses started, which was thought to have a direct impact on job creation and positive economic growth (Morris & Kuratko, 2020). Emerging entrepreneurship policy research in the early 2000’s questioned the validity of this singular measurement (Nielsen et al., 2021). Contrary to previously cited research, statistical data from the OECD showed that the number of start-ups in a country was affected more by economic trends than by policy initiatives. The growing body of research also suggested that it was not the number of new companies as such that had a positive macroeconomic impact, but rather the start-up and development of companies with high growth potential, often unicorns or gazelles, which has led some researchers to question the benefits of entrepreneurial policy (Acs, 2008; Minniti, 2008; Van Stel et al., 2005). In fact, some researchers, such Shane (2018) argue that we need to reduce these policies, as they provide little benefit.

Reflecting these views, entrepreneurship policy in western countries began to shift away from “volume” of new companies created to a qualitative measurement of potential impact of a high growth venture, resulting in debates on how the government defines quality in the context of a start-up as well as how to predict which start-up companies have the potential for high growth (Autio et al., 2007; Bager et al., 2015). Some researchers are very optimistic regarding controlling the supply and demand of entrepreneurship through government policy intervention: “Public policy and governance can shape virtually all the contextual determinants of the demand for entrepreneurship and over a longer time, the supply of entrepreneurs as well” (Hart, 2003, p. 8). There are opposing conclusions from other researchers who postulate the entrepreneurial field as more unruly, diverse, and influenced by society’s informal institutions and culture, and only to a limited extent influenced by political regulation (H. Aldrich, 1999). The reality is likely more context dependent. The objectives of most entrepreneurship policies of the present day are to increase the ease of doing business (e.g., by dismantling legal and legislative barriers), and to facilitate access to resources requisite to start-up and firm growth (Acs & Virgill, 2010). There is still little in the way of discussion and attention to those who are marginalized by such processes. Like other human endeavors, there is always a difference between the intent of policy and actual process (Merton, 1936).

Reflecting the above, entrepreneurship policy has been recognized as a particularly powerful component in the context of women entrepreneurship (Mason & Brown, 2014; Mazzarol, 2014; Stam, 2015). For instance, changes in policy in industrialized ownership has granted business ownership to women through policy changes, where previously a woman did not have the right to inherit, the right to own a business, or the right to borrow money without her husband’s co-signature (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2009). Despite this improvement, policy is a context-specific force; it is embedded in a country’s institutional and political framework. Consequently, this framework has considerable ability to influence entrepreneurial behavior regionally, nationally, and globally (Welter, 2011). Some researchers say this is particularly the case for women entrepreneurship in both developed and developing economies (Acs et al., 2017; Estrin & Mickiewicz, 2011). Foss et al. (2018) argue that good governance is a necessary prerequisite in supporting and stimulating growth oriented entrepreneurial activity (Méndez-Picazo et al., 2012); thus, effective entrepreneurial policies can help address market failures and promote economic growth (Acs et al., 2017). However, as we will illustrate policy does not consider the different institutional and political frameworks men and women function in.

Research on Gender and Entrepreneurship Policy

Understanding how policy initiatives are constructed is important to the field as they represent a political ideological articulation of prevailing normative socioeconomic values (Bennett, 2014), not the least of which is regarding gender Research conducted on gender-focused entrepreneurship policies include work by Mayoux (2001) and Orser and Riding (2006) while Minniti and Nardone (2007) have modeled gender effects on the start-up decision, independent of country-specific circumstances. Mayoux (2001) advocates for increased recognition and appreciation of women’s work, irrespective of its paid or unpaid status, and suggests a need to redefine what we consider “economic”. She emphasizes that the goal of encouraging women’s entrepreneurship goes beyond simply amplifying their role in economic growth and poverty reduction; it also involves guaranteeing that women are direct beneficiaries of these advancements. This endeavor is not solely about addressing women’s equal human rights issues, but also about removing barriers impoverished women face to experience this equality. The growing prevalence and debate around gender-specific small business training programs is evident, yet their nature and effects are poorly recorded. Orser and Riding (2006) analyzed the Women’s Enterprise Initiative (WEI), a program promoting female-led firms in Western Canada, focusing on its effectiveness, strengths and weaknesses, job creation, sustainability, incrementality, and the encouragement of business growth. They found that men and women desire distinct forms of business development support. Compared to a control group, WEI clients and female business owners prioritize personal growth factors like entrepreneurial skill assessment, self-confidence, and strategic management skills enhancement, while male counterparts focus more on operational aspects, including strategic management improvement and identifying growth opportunities (B. Orser & Riding, 2006).

Interest in entrepreneurship policy as a means of targeting marginalized, and disadvantaged populations in the economy has grown substantially in the last decade according to some researchers (Bennett, 2014). However, the lack of importance on gender remains. As an example, Foss et al. (2018) found that while other ecosystem components have been debated in the literature, the policy dimension has been underplayed in women’s entrepreneurship research. Foss et al. (2018) note that entrepreneurship policy, in general and from a gendered lens, is an under-researched area and conclude that policy implications on women entrepreneurship research are vague, conservative, and center on identifying skills gaps in women entrepreneurs individualizing the perceived problem to the entrepreneur herself. A bibliography of the gender and entrepreneurship literature by Link and Strong (2016) found that only 4% of articles addressed public policy regarding gender despite the establishment of national task forces in many areas of the world, representing a gap in academic inquiry. The establishment of these national task forces of major economies have sought to inform policymakers about the state of women’s entrepreneurship and the need for gender-focused policy interventions. Henry et al. (2017) and Ahl and Nelson (2014) provide insights into the current state of women’s entrepreneurship policies and perceptions. Their findings suggest that these policies often focus more on individual-level challenges rather than addressing broader institutional factors. A significant gap in gender-disaggregated data exists, particularly in the context of access to and utilization of small business support services. Additionally, women’s entrepreneurship policies are frequently marginalized within the larger economic policy framework, often relegated to agencies concerned with women’s safety and social welfare, rather than being integrated across key economic ministries. The common discourses identified in US and Swedish policy documents further reveal a tendency to view women entrepreneurs as an underutilized resource for national economic growth and subject to sex-based discrimination. These narratives often portray women entrepreneurs as inherently different from their male counterparts, for better or worse, thereby reinforcing the notion of women entrepreneurs as ‘other’ and perpetuating stereotypes and assumptions about gender differences in entrepreneurship.

Another common theme is that there is a lack of focus or concern with institutional barriers. This is reflected in how success is measured in policy interventions in order to fully understand the impact (or lack thereof) of women’s participation in entrepreneurship. As an example, Ahl and Nelson (2014) found that policies for women’s entrepreneurship are evaluated for design and effectiveness, but not for impact on the position of women with respect to equality or life opportunities. Their research also suggests that entrepreneurship policy is gendered, subordinating women’s entrepreneurship to neo-liberal goals, such as job creation and economic growth (the business case for policy intervention) rather than gender equity (Ahl & Nelson, 2014). Few of the policies articulated outcomes of gender equality, equity, or women’s economic empowerment (Coleman et al., 2019). Mason and Brown (2014) assert that women entrepreneurship public policy should address key issues plaguing current policy approaches, including the realization that one size does not fit all and that policy initiatives offered in isolation are likely to be ineffective. Possible directives to improve entrepreneurship policy geared toward women include lifting the research gaze from the individual entrepreneur and her business, instead addressing how process and context interact to shape the outcomes of entrepreneurial efforts (H. E. Aldrich & Martinez, 2001). Further, Zahra and Wright (2011) suggest that if entrepreneurship research is to influence public policy, there needs to be a dramatic shift in the focus, content, and methods.

Foss et al. (2018) support this view in principle but also acknowledge that the increased attention paid by both researchers and policymakers to the entrepreneurship ecosystem framework makes such a shift challenging as it involves an interdependency between actors, businesses, and organizations, and thus makes developing policy implications more complex. They ponder if the complexity of these challenges and the difficulty involved in effectively addressing policy issues has discouraged more policy engagement from scholars (Foss et al., 2018). In the 13-nation study, Henry et al. (2017) conclude that despite the growing numbers and contributions of women entrepreneurs, they are still not valued and recognized as an integral part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and environment. The authors agree that this weakness in the normative pillar puts a spotlight on the need for an entrepreneurial ecosystem that includes women entrepreneurs as well as public policies that address normative as well as regulative and cultural/cognitive factors (Henry et al., 2017). For example, Griffiths et al. (2013) summarize the conclusion from the literature review well by writing: "…in cultures where female entrepreneurship is perceived to have lower legitimacy in comparison with male entrepreneurship, women’s self-perceptions and attitudes can affect their likelihood of pursuing this career choice, and this constrains women-led new ventures (Baughn et al., 2006). In contrast, countries that provide normative support for women entrepreneurs, exhibiting admiration and respect along with gender equality, are likely to observe a higher level of female entrepreneurship activities (Baughn et al., 2006).

Bennett (2014) postulates that the centrality of entrepreneurship to contemporary socio-economic development has informed an extensive and diverse body of policy initiatives reflective of governmental interpretations of the role of entrepreneurship within society. Such initiatives also reflect and reproduce approaches to issues such as gender equality and the role of women. Bennett (2014) sees policy directives as not neutral in relation to gender positioning but rather as mechanisms whereby partisan ideas become actions through funded initiatives and are critical influences given their pervasive representation of normativity. Coleman et al. (2019) propose that in the face of perceived gaps between policy and practice, many groups such as industry associations, economic agencies, advocates, and scholars have called for the provision of gender-inclusive financing policies to strengthen the entrepreneurial ecosystems. Despite a growing body of literature that outlines gendered demand and supply side constraints, there is a dearth of knowledge about the underlying assumptions and impacts of policies designed to support women entrepreneurs’ access to financial capital (C. Brush et al., 2019; Leitch et al., 2018).

Defining Women, Female, and Gender

Feminist researchers encourage a distinction between sex and gender in order “to avoid biological determinism or the view that biology is destiny” (Mikkola, 2022, p. 2) whereby “‘sex’ denotes human females and males depending on biological features such as chromosomes, sex organs, hormones and other physical features) and ‘gender’ denotes women and men depending on social factors including social role, position, behavior or identity” (Mikkola, 2022, p. 2). Gender norms influence commonly accepted ways of how individuals see themselves and interact with others as well as the distribution of power and resources in society (Canadian Institute of Gender and Health, 2012; Johnson et al., 2007; Tannenbaum et al., 2016). Researchers are now recognizing that gender requires an intersectional approach since it can be structured by and within ethnicity, indigenous status, social status, sexuality, geography, socioeconomic status, education, age, disability/ability, migration status, and religion (Bauer, 2014; Bowleg, 2012) Each of these topics make creating policy more complicated as different intersections will have diverse experiences. A married immigrant woman with children and a lack of job skills will have a very different experience in the market place than would an unmarried scion from a wealthy background who intended an Ivy league institution. Based upon our social constructivist feminist entrepreneurs, are understood as gendered in both concept and practice (Ahl, 2006; Ahl & Nelson, 2014; C. G. Brush et al., 2009; Pettersson, 2004)

Feminist Approaches to Entrepreneurship

Feminist theory is an extension of the feminist ideology in different disciplines such as, but not limited to anthropology, art, literature, philosophy, politics, business, and economics. Feminist research aims to understand and deconstruct gender inequality ingrained in the structure of societies (Hirudayaraj & Shields, 2019). Feminist theory is commonly categorized in three perspectives: feminist empiricism, feminist standpoint theory, and post-structural feminism (Calás & Smircich, 1996; Harding, 1987). What they have in common is what underlies feminism—the recognition of women’s subordination in society and the desire to rectify this (Pettersson et al., 2017). Feminist research provides interpretations and explanations for women’s subordination but since the perspectives/approaches differ in terms of how gender is conceptualized, how obstacles for gender equality are defined, and in ontological and epistemological assumptions (Campbell & Wasco, 2000), policy outcomes will differ depending on which feminist approach is favored.

Feminist empiricism is criticized as being essentialist in character because it assumes certain traits are unique to men and women. This approach reinforced the sameness between men and women, taking little account of within-sex variation. Inspired by the early work of West and Zimmermann (1987) and their concept of “doing gender”, social scientists such as Di Stefano (1990), Butler (1990), and Haraway (1991) introduced gender-as-process (“poststructuralist feminism”).

Feminist Empiricism: Liberal Feminist Theory and Postfeminism

Holmes (2007) describes liberal feminist theory as a theory that sees men and women as essentially similar, equally capable, and as rational human beings. It builds on 19th Century liberal political theory which envisioned a just society as one where everyone can exercise autonomy through a system of individual rights. Liberal feminism aims for equal property and legal rights, women’s suffrage, equal access and representation and assumes that women and men have similar capacities, so if only women are given the same opportunities as men, they can achieve equal results (Holmes, 2007). Liberal feminism thus sees discriminatory structures as the reason for women’s subordination. The fight for equal pay and equal access to business ownership is an example of liberal feminist struggles. Any differences between men and women’s achievements are explained by organizational or societal discrimination. Entrepreneurship research that is conducted within this theoretical framework investigates barriers (such as a lack of access to capital or training) and the focus is often directed towards differences between men and women (including demographic, behavioral, and cognitive differences), instead of problematizing institutional practices (Pettersson et al., 2017). Further, Foss et al. (2018) found that research using this perspective maps the presence of women in business, it maps their characteristics, or it maps size, profit, or growth rate differentials between men and women-owned businesses (e.g., Anna et al., 2000; Wicker & King, 1989).

The role of the entrepreneur in the liberal feminist theory is to recognize and capitalize on opportunity with performance measures focusing solely on profit maximization and revenue growth. Firm governance is predicated on owner or private shareholders, where control is formal, centralized, and hierarchical (B. Orser & Elliott, 2015). Women are positioned as ‘untapped resources’ or assets for economic growth and are lacking in comparison to men in entrepreneurial abilities, characteristics, and knowledge. Women need to be “fixed” to participate in entrepreneurial activity and the prevailing discourse is that women’s businesses are too few, too small, or are growing too slowly (Pettersson et al., 2017).

Policy implications from a liberal feminist perspective focus on resource allocation or women’s equal access to resources. Policy suggestions include equal access to business education and training or legislation prohibiting banks from sexist and antiquated practices. Policies address individual-level constraints through targeted interventions such as financial training for growth-oriented women business owners and gender-sensitive training (Coleman et al., 2019). Policy interventions prioritize business owners who are white, heterosexual, and middle-class (Pettersson et al., 2017) or engaged in science, technology or engineering. While feminist empiricism is useful in making women’s presence and condition visible, it has been criticized for accepting current (male) structures and simply adding women (Foss et al., 2018).

Postfeminism shifts emphasis away from organizational, structural, and cultural causes of sexism to focus on the choices, behaviors, and self-understanding of individual women (Harquail, 2020) but says little about what is expected of men. It ignores a system level cause of gender inequality and the subtle manifestations of patriarchy and disingenuously claims that a woman’s individual agency is the best approach for making minor necessary improvements in her work prospects (Harquail, 2020).

Lewis et al. (2022) suggest postfeminism is a polysemic concept, recognizable through its selective choice of liberal feminist values of choice, empowerment and agency based on the neoliberal principles of individualism, self-governance and entrepreneurialism. This definition is further supported by research conducted by Ahl and Marlow (2021), Gill (2017), Lewis et al. (2017), and McRobbie (2009). Recent gender and entrepreneurship research has positioned postfeminism as a critical concept to investigate the kinds of entrepreneurial subjects women are called to become (Lewis, 2014; Nadin et al., 2020; Pritchard et al., 2019; Sullivan & Delaney, 2017). Some scholars see postfeminism as a regression in achieving feminist goals and, as the name implies, we have somehow moved beyond the need for feminism and its tenets.

Postfeminism is said to have evolved as a cultural response to the challenges feminism has posed and the progress feminism has made, including limited acceptance of feminist ideals and perspectives, as well as backlash against and resistance to full gender equality and social justice (Harquail, 2020). Gill et al. (2017) see postfeminism as a way of defining the entanglement of feminist and anti-feminist ideals where people see the progress of feminism even while experiencing ongoing sexism. Although postfeminism is about feminism it is not typically considered a feminist perspective but rather a reflection of deeply rooted sexism and an incomplete understanding of feminism that gets in the way of understanding gendered inequality and sexism in organization. It is, at best, a series of claims and a set of positions about whether sexism still exists and whether feminism is still needed or useful (Gill, 2008). Accordingly, the policy implications of postfeminism may be nil or limited.

Poststructural Feminism

Poststructuralism refers to a loose collection of theoretical positions influenced by post-Saussurean linguistics, Marxism psychoanalysis, feminism and the work of Derrida, Barthes, and Foucault (Gavey, 1989). Poststructuralist approaches are concerned with language as a system of difference whereby texts and language are seen as a politics of representation that produce gender and both universal and objective knowledge claims are called into question (Pettersson et al., 2017). Poststructuralist feminist theory emerged from the observation that discrimination may be based on any social category, not just sex (Hooks, 2000), and from postmodern critiques of grand narratives (Lyotard, 1984), such as those justifying social orders by natural sex differences (Coleman et al., 2019). Gender is defined as socially constructed through history, geography, and culture and therefore what appears as masculine and feminine traits vary over time, place, and discourse and are constantly renegotiated. Gavey (1989) suggests poststructural theory recognizes there is no absolute truth and instead all identities are transient and relative. Researchers are unable to define a real or authentic personality since the self is produced differently depending on the discursive environment (Francis, 2002). Poststructural feminism aims to challenge the essentialist notion that women are made up of a single, static category of identity and instead frames “woman” as emergent and constantly shifting, multifaceted, and constructed within competing discourses (Butler, 1990). Further, poststructural feminism provides a framework for understanding the ways in which women simultaneously engage in resistance and are subjected to power by emphasizing the complexity and shifting nature of power relations (St. Pierre, 2000).

Calás et al. (2007) characterize gendering processes and practices as the product of power relations which have emerged from historical processes, dominant discourses, institutions, and epistemological arguments. It is not preoccupied with what men and women are but rather how masculinity and femininity is constructed and how this affects social order, particularly in relation to gender and power. The poststructuralist feminist approach more specifically “…explores the connections between language, subjectivity, social organization, and power, and their ramifications for gender dynamics in all walks of life” (Prasad, 2005, p. 165). Texts and language are seen as a politics of representation that produces gender and “…deconstructive studies that employ these approaches analyze concepts, theories, and practices of entrepreneurship, and how they construct (women) entrepreneurs” (Pettersson et al., 2017). Gender is socially constructed through discourse that governs human interactions and how male and female entrepreneurs view themselves and each other, including the assumed male norm for entrepreneurship that consigns women to the role of “other,” and the belief that women entrepreneurs and their businesses are lacking in terms of size, profits, growth trajectories, return on investment or industry representation (Coleman et al., 2019).

Poststructuralist feminism provides us with a means of challenging assumptions, structures and discourse that are implicit within women’s entrepreneurship policy. Possible policy suggestions with a poststructuralist approach could be mandatory gender awareness training among mainstream business advisors rather than a separate advisory system where women advise women. Literature reviews have found the poststructuralist perspective to be sparsely represented in policy creation but fruitful in revealing how gender discrimination is achieved (Neergaard et al., 2011). The research using this perspective points out the male gendering of the entrepreneurship field and claims that common and established research practices through their assumptions, problem formulations, research questions, methods, and interpretation of results subordinate women from the start (Ahl, 2006). The relationship between the use of feminist perspectives and policy implications in research on gender and entrepreneurship is an unexplored theme (Coleman et al., 2019).

Understanding the intersection of gender and entrepreneurship through the lens of poststructural feminism allows for the examination of the systemic biases that perpetuate discrimination. This theoretical perspective suggests that gendered assumptions within the entrepreneurship ecosystem are deeply embedded and perpetuated through language, practices, and policies.

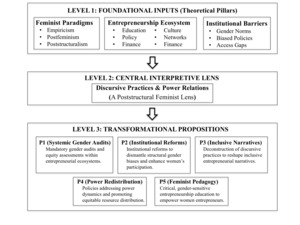

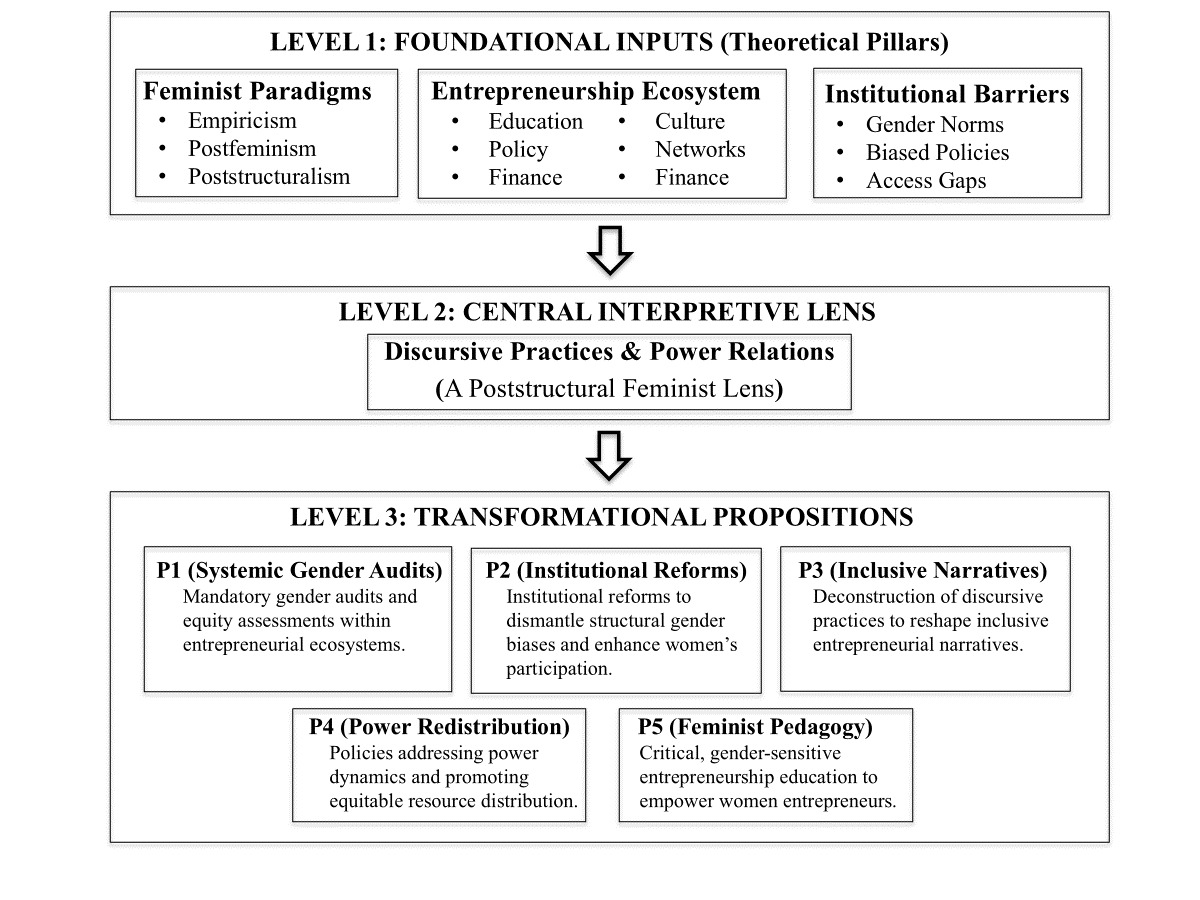

To synthesize the theoretical and structural components discussed above, we propose an integrated conceptual model that visually captures how feminist paradigms, ecosystem elements, and institutional barriers intersect (Figure 1). Specifically, Figure 1 presents a layered conceptual model where feminist theoretical paradigms and ecosystem barriers are interpreted through discursive and power relations, generating five systemic propositions for policy and research transformation.

We propose the following theoretical propositions:

Proposition 1: Implementing systemic changes within the entrepreneurship ecosystem, such as mandatory gender audits and equity assessments, will significantly reduce gender-based discrimination and improve the success rates of women entrepreneurs.

Proposition 2: Systemic institutional changes, rather than individual-level interventions, are crucial for addressing gender disparities in entrepreneurship. Institutional norms and practices significantly influence the entrepreneurial success of women. By targeting and reforming these institutional structures, policies can dismantle systemic barriers and foster a more inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystem, thereby enhancing the participation and success rates of women entrepreneurs.

Reframing Entrepreneurship: Feminist Theory and Systemic Change in Policy and Practice

Ahl and Marlow (2012) lamented that the entrepreneurship research agenda in a broad sense has become embedded within a series of gendered assumptions, which rest upon weak foundations. Part of this foundation, they suggest, is that entrepreneurship offers gender neutral meritocratic opportunities to individuals to help them realize their potential for innovation and wealth creation; that the normative entrepreneurial character is male, and his ventures outperform those owned by women. When officials use policy interventions to address perceived performance gaps among women, these interventions are typically measured trough an economic lens (Ahl & Marlow, 2012). The focus on individual women and their businesses does not explain current patterns of women’s entrepreneurship and unjustly blames women for structural circumstances beyond their control, something that continues today (Bradley, 2007; Dimick et al., 2025). This discourse, outlined in the literature review, underpins the hierarchical gendered ordering where femininity is associated with deficit and of entrepreneurship emerges as the unquestioned norm (Bruni et al., 2004; Foss, 2010; Marlow, 2013; Richard, 2025).

On the other side of the chasm is feminism, moving more towards theorizing as opposed to application, offering and teasing a new path forward yet resisting the field of entrepreneurship in her stubbornness. The authors are suggesting a new way forward for women entrepreneurs is a revolution that can only be driven by a bridge built over the deep fissure history created between the separation of entrepreneurship research and feminist research. That is, to provide context on the more traditional path women entrepreneurship researchers have used feminism in the women entrepreneurship domain (such as liberal feminism and postfeminism) and how the feminist approaches that exist on the fringes (such as poststructuralist feminist theory) might just be what we need to trigger a tectonic shift, closing the chasm completely and helping to inform inclusive entrepreneurship policy that allows for and encourages participation for rationales beyond economic advancement of the country and consider outcomes such as quality of life.

Feminist scholars have long argued that most entrepreneurship policies are gender blind and lack the mandate to address underlying mechanisms that impede gender equality (Ahl & Nelson, 2014; Pettersson et al., 2017). Coleman et al. (2019) offer three supporting points to this argument. First, entrepreneurship policies prioritize revenue growth, masculine culture, and male-dominated industry sectors (Rowe, 2016), and rarely articulate socio economic priorities, such as equity, inclusion, and poverty reduction. Second, the historical lack of systematic, gender-sensitive program evaluation processes impede the construction of inclusive, evidence-based entrepreneurship policies. Orser et al. (2019) address this gap and provides guidance. However, the lack of funding for agencies mandated to conduct gender-based analysis stifles progress by these agencies tasked with designing entrepreneurship or innovation policies. Further, a study done by Orser et al. (2011) examined how feminist attributes are expressed within entrepreneurial identity and suggest that policy makers and other stakeholders should check for unintentional gender bias both in language and decision making. Agencies who promote women’s entrepreneurship are left to “push” policy recommendations through various, often tangentially related, ministries because they are not able to respond to gender-focused policy priorities (B. J. Orser, 2017, p. 122). Finally, Pettersson et al. (2017) observed that the absence of feminist theory in research on women’s entrepreneurship is a missed opportunity to inform public policy. Current academic discourse about feminist-informed entrepreneurship policy is obscure or idealistic, making it challenging to extract pragmatic solutions to inform entrepreneurship policy and therefore are overlooked or dismissed as being “too academic” (Pettersson et al., 2017). This is a point not to be taken lightly; the authors are proposing that the path forward towards improved inclusive entrepreneurship policy involves applying feminist theory to entrepreneurship in a way that can be useful and practical, ensuring that it is easily accessible to women’s enterprise advocates, demonstrating that it can align with the principles of entrepreneurship policy. This has proven to be challenging to date. As an example, Foss et al. (2018) applied a feminist lens to examine the implications of entrepreneurship policies within academic publications between 1983 and 2015 and concluded that policy implications were inherently gender biased, individualizing problems to women themselves, regardless of the feminist perspective used by the authors. The challenge thus lies in building a case using a feminist approach that shifts policy from individualizing problems to recognizing problems within the support structure (i.e., the entrepreneurship ecosystem).

Advancing research on gender and entrepreneurship requires a theoretical shift that incorporates poststructural feminist perspectives. Traditional research methodologies, while valuable, often fail to capture the complex and dynamic nature of gender dynamics within entrepreneurship ecosystems. By embracing poststructural feminist approaches, we can better understand and address the systemic and discursive practices that perpetuate gender disparities. Based on this perspective, we propose the following theoretical propositions:

Proposition 3: Poststructural feminist perspectives suggest that discursive practices within the entrepreneurship ecosystem construct and perpetuate gendered identities and roles, which influence the entrepreneurial engagement and success of women. By deconstructing these discursive practices and promoting inclusive narratives, policies can reshape the social constructs around entrepreneurship and foster a more equitable environment for women entrepreneurs.

Proposition 4: Poststructural feminism posits that power relations within entrepreneurship ecosystems are fluid and negotiated through everyday interactions and institutional practices. These power dynamics influence access to resources and opportunities for women entrepreneurs. Policies that actively seek to disrupt these power imbalances and promote equitable resource distribution can enhance the participation and success of women in entrepreneurship.

Proposition 5: Embracing poststructural feminist approaches in entrepreneurship education can transform the entrepreneurial mindset and skills of aspiring women entrepreneurs. By integrating critical perspectives on gender and power into entrepreneurship curricula, educational programs can equip women with the tools to navigate and challenge systemic barriers, ultimately leading to more successful entrepreneurial outcomes.

Conclusion

This research has laid out and discussed both the limitations and implications of current research on entrepreneurship and gender. The epistemological assumptions of mainstream entrepreneurship with its focus on economic growth has limited the integration of feminist thinking into the mainstream literature. An example of this trend would be the work of Shane (2018), who put forth the thesis that only a handful entrepreneurial activities actually provide benefit to society from the perspective of economic growth. Although Shane’s insight is correct, he ignores the personal meaning that could occur through an entrepreneurial endeavor. Morris and Kuratko (2020) published a response to Shane (2018), arguing that a small entrepreneurial endeavor, while not increasing the benefits to society in higher productivity, does have benefits to the individuals involved. Many women are forced, due to structural discrimination, to become necessity entrepreneurs. As such, both research and policy should place less emphasis on unicorns and more on funding businesses that could help launch women (and other discriminated groups) into careers.

Likewise, another focus, based on feminist theory, should be the idea of social entrepreneurship–which is the idea enterprises should have a focus beyond profits such as social impact. Indeed, social entrepreneurship is an important concept since it often reduces institutional failure. However, again, such an approach could lead to women being driven to social entrepreneurship because of the assumption that women are more prosocial. Accordingly, whatever policy matters that is suggested by politicians, bureaucrats or advocates should have its underlying assumptions addressed.

Further, the authors suggest that researchers should also expand their horizons to consider more holistic and qualitative approaches to research. Namely, the focus of entrepreneurship has had two complementary aims. The first is theory building, which is to say that entrepreneurship scholars have sought either to extend influential economic, management, sociological and psychological theories into the realm of entrepreneurship research. The second aim has been to empirically test these theories in entrepreneurship. As a relatively new field of research, entrepreneurship scholars should emulate fields that are legitimate in the presence they are embedded.

Practical Implications

This study offers several key insights that can inform both entrepreneurship educators and small business consultants, equipping them with a more nuanced understanding of gender dynamics in entrepreneurship and enhancing their ability to support women entrepreneurs effectively. Although these ideas have been proposed by other scholars, we seek to recast them based on our theorization. This is not a call for a radical restructuring of the curriculum; rather, we suggest that it should engage more deeply with these differences.

Implications for Entrepreneurship Educators

Entrepreneurship educators play a crucial role in shaping the next generation of entrepreneurs. However, the dominant pedagogical models in entrepreneurship education often reinforce traditional, male-centric narratives of entrepreneurial success. This study underscores the need for educators to adopt a more inclusive approach that acknowledges and addresses the structural barriers that women entrepreneurs face. Entrepreneurship programs worldwide have made significant strides toward gender-aware pedagogy over the past decade (Botha, 2020; Henry et al., 2015). Rather than proposing entirely new directions, our recommendations below consolidate and extend practices already evident in leading curricula.

1. Revising Curricula to Integrate Gender Perspectives

Most entrepreneurship programs emphasize opportunity recognition, risk-taking, and high-growth strategies, qualities historically associated with male entrepreneurs. However, as noted by Ahl and Marlow (2021), these attributes do not necessarily align with the diverse motivations and challenges of women entrepreneurs. In fact, we go further and suggest that these traditional attributes and the associated entrepreneurial roles are constructed through gendered discourse and reflect (intentionally and unintentionally) gender norms. Entrepreneurship educators should integrate feminist theory into their curricula, incorporating discussions on systemic biases, gendered barriers, and alternative measures of success beyond financial growth (Lee et al., 2024). This would include a deep critique of gender biases. Likewise, the entrepreneurial curriculum should reflect different outcomes such as fostering a more equitable learning environment that challenges traditional gender roles and expectations.

2. Incorporating Experiential Learning That Addresses Gendered Challenges

Traditional business simulations and case studies often reflect male-dominated industries and leadership styles (Lee et al., 2024). To foster inclusivity, educators should use case studies featuring diverse entrepreneurs, particularly women in non-traditional sectors. Additionally, role-playing exercises and mentorship programs that connect students with successful women entrepreneurs can provide critical insights into navigating gender biases in business environments. For example, educators should incorporate experiential learning opportunities that reflect gendered challenges and dynamics such as cases from non-traditional sectors (e.g. necessity entrepreneurship) that could provide future entrepreneurs and policy makers with a greater understanding of issues faced by those who do not enjoy their educational opportunities.

3. Encouraging Diverse Funding and Growth Strategies

Women entrepreneurs often face unique financial barriers, including reduced access to venture capital and loans (Coleman et al., 2019). These barriers are reflected in the deeply rooted in the gendered assumptions about what constitutes entrepreneurial success as well as the institutional structures, based on those assumptions, that perpetuate barriers—despite, the best intentions of policy makers and educators. Entrepreneurship educators should ensure that students understand diverse funding mechanisms, such as microfinance, cooperative funding models, and grants tailored for women-led businesses. Providing exposure to alternative financing strategies enables students to explore entrepreneurial paths that align with their values and resources. Our suggestion her builds off current pedagogy and moves that pedagogy to understanding a broader of that entrepreneurs face different realities. In fact, it is worthwhile to note, one of the most successful social entrepreneur organizations, Teach for America, came from a sociology student. We suggest that there is still low hanging fruit.

4. Developing Critical Thinking on Policy and Ecosystems

Entrepreneurship education often focuses on individual agency while underemphasizing the impact of policies and institutional structures on business success which are based on discriminatory frameworks (Dimick et al., 2025). Educators should encourage students to critically analyze entrepreneurship ecosystems, recognizing how policies, networks, and cultural expectations shape business outcomes differently for men and women. By integrating feminist perspectives into policy analysis, educators can help students recognize how governmental interventions may operate within gendered frameworks that inadvertently reinforce gender disparities. This shift in focus can foster a deeper understanding of how systemic and institutional changes are needed to create a more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Implications for Small Business Consultants

Small business consultants provide direct guidance to entrepreneurs, shaping their strategic decisions and business trajectories. To better support women entrepreneurs, consultants must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and consider the specific barriers and opportunities that women face in entrepreneurial ecosystems.

1. Recognizing the Limitations of Traditional Business Models

Many consulting frameworks emphasize rapid scaling and high-risk strategies, which may not align with the goals or realities of women entrepreneurs, particularly those balancing caregiving responsibilities (Marlow, 2020). Consultants should adopt a more flexible approach that considers different definitions of success, such as financial stability, community impact, or sustainable growth.

2. Addressing Gendered Barriers in Business Development

Women entrepreneurs frequently encounter difficulties in securing funding, accessing male-dominated networks, and being taken seriously by investors (Ahl & Nelson, 2014). Consultants must actively address these issues by helping women entrepreneurs develop tailored fundraising strategies, connect with women-focused investment networks, and build advocacy skills to counteract gender biases in negotiations.

3. Challenging Implicit Bias in Advisory Practices

Unconscious biases can shape the advice consultants give to entrepreneurs. Research by Foss et al. (2018) suggests that many business support programs frame women entrepreneurs as ‘lacking’ in key competencies rather than recognizing structural inequities. Consultants should undergo gender awareness training to identify and challenge their own biases, ensuring that their guidance does not reinforce stereotypes but rather empowers women to leverage their strengths.

4. Advocating for Policy Change and Inclusive Ecosystems

Small business consultants often serve as intermediaries between entrepreneurs and larger business ecosystems, including financial institutions, government agencies, and industry groups. They should use their influence to advocate for more inclusive policies, such as improved access to funding for women-led businesses, gender-sensitive training for investors, and the creation of mentorship programs that connect women entrepreneurs with experienced business leaders.

By integrating gender-aware approaches, entrepreneurship educators and small business consultants can play a significant role in dismantling structural barriers and fostering a more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem. Educators must rethink traditional curricula and teaching methods to reflect the realities of diverse entrepreneurs, while consultants must actively challenge biases and advocate for systemic change. Ultimately, creating a supportive environment for women entrepreneurs requires a concerted effort to shift from individual-focused solutions to systemic interventions that promote equity and opportunity for all.

Recent policy turbulence underscores the importance of embedding flexibility and local responsiveness into inclusive-entrepreneurship strategies. In the United States, 2024-2025 has seen a cascade of legislation dismantling Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) infrastructures in public higher education. Texas Senate Bill 17, enacted in 2023 and effective 1 January 2024, now prohibits public universities from maintaining DEI offices or requiring diversity statements (Texas Legislature, 2023). National trackers list over 100 anti-DEI bills introduced across 29 states (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2025). Such rollbacks threaten externally funded EDI programmes and could narrow the institutional space for gender-inclusive entrepreneurship initiatives.

Yet the trajectory elsewhere is markedly different. Canadian universities have reaffirmed sector-wide EDI commitments through a 2023 progress report that links federal research funding to measurable inclusion targets (Universities Canada, 2023). At supra-national level, the European Union’s Erasmus+ Programme Guide 2025 dedicates billions of euros to projects that prioritise inclusion and diversity (European Commission, 2024). These contrasting paths reinforce our argument that public policy is a volatile, but not solitary, lever; when governmental support recedes, curricular innovation and ecosystem partnerships, already central to best practice, become critical buffers, while favourable policy environments can accelerate scale-up. Our propositions are therefore intentionally modular, allowing educators and policymakers to adapt them to contexts ranging from acute DEI retrenchment to active equity expansion.

Limitations

The propositions presented in this manuscript remain conceptual and have not yet been empirically tested. They are intended as theoretically informed pathways emerging from the extensive body of literature on gender and entrepreneurship. While the paper outlines potential practical implications, it is acknowledged that similar interventions have been previously attempted with limited success in transforming women’s entrepreneurial experiences. This limitation may stem from the fact that such interventions were often informed by policy perspectives grounded in traditional or outdated conceptualizations of gender. A recurring issue in the literature is the tendency to replicate historical policy frameworks that prioritize economic growth, rather than equity or structural reform.

Given this context, there is a clear need to reimagine and redesign policy interventions through alternative theoretical and methodological lenses. Empirical testing of the propositions advanced here presents significant challenges, particularly due to the limited availability of quantitative data that adequately capture the nuanced issues under consideration. Future research would benefit from employing methodologies capable of addressing complexity and contextual depth, such as qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), ethnographic inquiry within entrepreneurial support organizations, or discourse analysis of institutional narratives. In particular, participant-observer studies that closely examine the lived experiences of women entrepreneurs are recommended to deepen understanding and inform meaningful policy change.

Future Research

This paper provides several insights into future research ideas. First, it is recommended to study women’s entrepreneurship through the lens of feminist theory, noting the differing environments that men and women face in entrepreneurial ecosystems. Second, to expand on point one, the complex interplay between government policy/entrepreneurial intervention and social mores (e.g. beliefs about women) needs to be examined. There has been some work conducted on this issue (e.g., Haugh & Talwar, 2016). However, too often, scholars tend to downplay other social forces (such as the lack of supportive networks) in their focus on government intervention (Muldoon et al., 2024). Third, in crafting research, researchers need to understand that men and women may see entrepreneurship from a different perspective (or likewise the same perspective), the academic literature tends to spend too much time on unicorns, at the expense of smaller corporations or non-profits. Therefore, researchers need to be hyper-aware of what differences may exist between the needs and desires of women versus male entrepreneurs. The literature summarized indicates this is a highly complex and nuanced situation.