1. Influence of CEO and Firm Characteristics on SME Internationalization: Evidence from California

When small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) participate in global markets, benefits include increases in investment, an increase in managerial capabilities, employment growth, and increased productivity and competitiveness. As a result, successful internationalization is a desirable goal for SMEs as well as the economy in which the company operates (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2018; Wagner, 2012; World Trade Organization, 2016). Internationalization is often described as a geographical expansion of economic activities across the country’s national borders (Ruzzier et al., 2006). To emphasize internationalization’s importance, U.S. companies that export grow faster and are nearly 8.5 percent less likely to go out of business than non-exporting ones (Bose, 2017). In addition, about 26 percent of companies that trade internationally significantly outperform their market (Bose, 2017).

While California specifically, and the U.S. economy in general, has benefited from participation in global markets, a recent backlash against free trade policies across the world makes it even more important to better understand exactly what is needed from companies to integrate themselves into the global economy. This need is likely enhanced, as it appears that the “rising globalization wave” that may have been carrying more SMEs into doing business globally, may be ebbing with a potential trade war between the U.S. and China, as well as global trade pullbacks (e.g., Brexit) and COVID-19-related travel and trade issues, which may be part of a wide-reaching structural trend toward reduced internationalization.

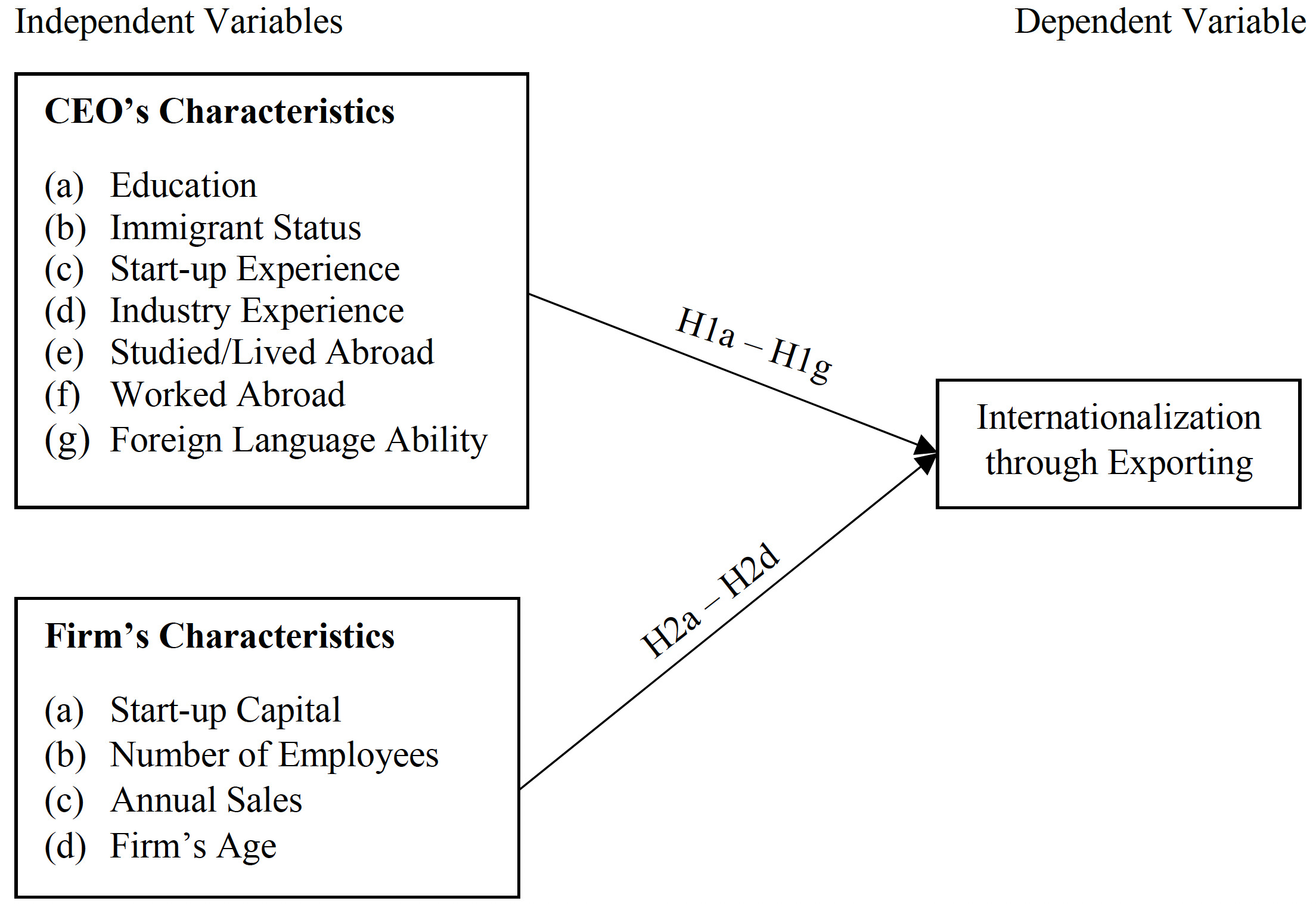

As a result, the purpose of our study is to address two interrelated issues, the relative importance of the CEO’s characteristics of an SME – the entrepreneurial factors – vis-à-vis its firm-specific factors in the SME’s internationalization. In other words, the objective of our study is to explore what entrepreneur and firm characteristics are associated with SME internationalization. By better understanding the relationship between these characteristics and SMEs’ internationalization, effective policies and practices can be designed along with providing more appropriate encouragement and support for the internationalization of these firms. These objectives are also consistent with the research gaps identified by Cavusgil and Knight (2015), Verbeke et al. (2014), and Tsao et al. (2018).

To accomplish these objectives, the study uses two completely independent datasets (one using archival data and one using survey data collected for this study) to test the proposed hypotheses. More specifically, an archival dataset (the Survey of Business Owners, or SBO, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau) to test a series of initial relationships. Then survey data collected for this study is used to corroborate the findings from the SBO data and, importantly, to test several hypotheses which could not be tested using the archival SBO data.

For all of the hypotheses across both data sets, logistic regression is used to determine whether the variables examined are associated with the dichotomous outcome of whether an SME internationalizes or not. By doing so, the study offers novel contributions into the phenomenon of SMEs’ internationalization, CEO’s characteristics, and firm-specific advantages of SMEs.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

SMEs are generally defined as firms with less than 500 employees (U.S. International Trade Commission, 2010). In the academic literature, the process of SME internationalization is usually explained by one of two major perspectives. The first perspective suggests that SMEs’ internationalization occurs through an incremental process involving a sequence of steps or stages, starting from a domestic market and gradually expanding to international markets. This gradual expansion happens as new market knowledge is acquired in accordance with a learning process, and resources are increasingly committed to those markets (Bilkey & Tesar, 1977; Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009). The second perspective, derived from international entrepreneurship, claims that a firm can reach multiple global markets from inception (Coviello et al., 2011; Knight & Cavusgil, 1996; McDougall & Oviatt, 2000; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994). These firms are often referred to as “born global” or international new ventures (Crick, 2009).

In addition to the perspectives discussed above, scholars have started using other approaches to enhance our understanding of SMEs’ internationalization. Two of these approaches are the upper echelons (e.g., Acar, 2016; Hsu et al., 2013; Laufs et al., 2016; Tsao et al., 2018) and internalization (e.g., Verbeke et al., 2014) theories. Even though these perspectives have been used to study the internationalization of SMEs, their use has been limited.

Upper echelons theory examines CEO or founder characteristics to explain whether SMEs will internationalize. For example, Tsao et al. (2018) used upper echelons and suggested that larger sample sizes from a developed economy might be needed, to further validate and replicate their findings of the influence of family heterogeneity on SMEs internationalization outside of Asia.

Internalization theory researchers, on the other hand, have examined firm-specific advantages which influence firm internationalization. Importantly, firm-specific advantages (FSAs) and their impact have been assessed individually, but as highlighted by Verbeke et al. (2014) have not been sufficiently tested empirically on a large sample. The authors further suggest, that in addition to traditional FSAs like firm size, knowledge (as represented by R & D), marketing ability, and industry type the founding-entrepreneur characteristics can be interpreted as FSAs (Verbeke et al., 2014).

International business (IB) has been traditionally dominated by large, multinational enterprises (MNEs). However, through advances in communication, transportation, and information technologies, SMEs are playing an increased role in IB (cf., Hillary, 2017; Knight & Kim, 2009; World Trade Organization, 2016). Decreased trade barriers and changes in global value chains have also paved the way for SMEs to become more active in global trade (Knight & Cavusgil, 2004; World Trade Organization, 2016). According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, a total of 73,528 companies exported from California locations in 2015 (U.S. Department of Commerce et al., 2018). Of those companies, 96 percent (70,350) were SMEs with fewer than 500 employees (U.S. Department of Commerce et al., 2018). In 2014, California had both the most exporters (75,722) and the most SME exporters (72,591) of any state in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Commerce et al., 2018).

Only about one percent of U.S. SMEs export (U.S. Department of Commerce et al., 2018). In addition to having a large domestic market, one reason for such low representation is that SMEs face various obstacles when trying to internationalize their businesses. Leonidou (2004) identified several impediments hindering SMEs’ export development and categorized them as internal (e.g., limited information about foreign markets, lack of human resources, and lack of working capital) and external (e.g., tariffs, differences in the exporting process, political instability in foreign markets). Moreover, SMEs (in comparison to larger firms), have the added liabilities relating to newness, smallness, and inexperience in addition to the liability of foreignness (Wright et al., 2007). According to Acar (2016), the survival of SMEs in emerging markets increasingly depends on their ability to exploit opportunities in foreign markets. Given their limited resources, exporting is one of the most viable modes of entry into foreign markets for SMEs (Acar, 2016).

Cavusgil and Knight (2015) suggest that researchers should investigate why some firms internationalize early, while others internationalize later, or some not at all. They suggest that scholars should look at the role founders, managers, organizational resources, partner networks, external factors, and other factors play in affecting the nature of internationalization. Since the focus of this paper is on SMEs, consistent with others, we use the terms entrepreneur, founder, owner, and CEO interchangeably (Picken, 2017).

2.1. CEO Characteristics

In order to understand the relationship between CEOs’ characteristics and SME internationalization, we apply the framework of the upper echelons theory (Hambrick, 2007; Hambrick & Mason, 1984). The upper echelons theory explains relationships between organizational outcomes and managerial background characteristics. Even though this theory was developed in the context of large firms and top management teams (TMT), researchers have used the underpinnings of the theory to explain the association of CEO observable demographic indicators (such as education level, business degree, age, gender, ethnicity, and tenure length) to SME performance (Hsu et al., 2013; Laufs et al., 2016; Marcel, 2009; Tsao et al., 2018). Acar (2016) focused on regularly examined upper echelons attributes like age, education, and tenure, to assess whether TMT composition influenced SMEs’ export levels. In addition, Laufs et al. (2016) examined the impact CEO characteristics have on SMEs’ decisions regarding equity and non-equity foreign market entry modes.

Based on the research by Verbeke et al. (2014) and suggestions from Coviello et al. (2017) and Coviello (2015), looking at entrepreneurs’ characteristics is important since it provides insight regarding the individual’s role as a core micro foundation of the internationalization process. Previous research has established a link between college-educated founders of SMEs and their propensity to export due to the founder’s ability to problem solve and to access necessary information and resources (cf. Ganotakis & Love, 2012; Stucki, 2016). Therefore, our first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1a. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has a university degree.

Several other authors have linked the founder’s immigrant status to their success as exporters. One of the plausible explanations is that immigrant entrepreneurs have access to valuable networks due to their personal relationships in markets abroad (cf. Drechsler et al., 2019; McDougall et al., 1994). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO is an immigrant.

Moreover, founders who have previous start-up or industry experience possess the necessary knowledge to expand and grow their business more rapidly (cf. Federico et al., 2009; McDougall et al., 2003; Verbeke et al., 2014). The notion of previous experience also applies to having an international experience either through education (e.g., study abroad), living abroad, or work experience overseas whereby the entrepreneur can leverage the networks created as part of these experiences (cf. Crick, 2009; D’Angelo & Presutti, 2019; Knight & Cavusgil, 1996; McDougall et al., 1994). Often these experiences influence the entrepreneur to create a global vision from inception (cf. D’Angelo & Presutti, 2019; McDougall et al., 1994). These experiences and knowledge also allow firms to minimize the uncertainty (thereby reducing the liability of foreignness) and take advantage of opportunities abroad (cf. D’Angelo & Presutti, 2019; Madsen & Servais, 1997). Based on this evidence, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 1c. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has previous start-up experience.

Hypothesis 1d. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has previous industry experience.

Hypothesis 1e. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has studied/lived abroad.

Hypothesis 1f. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has worked abroad.

Other studies have found that in addition to previous international experience, time spent abroad, and IB knowledge, foreign language ability also plays a role in contributing to the international outlook of the decision-maker (Lloyd-Reason & Mughan, 2002). Fernández-Ortiz and Lombardo (2009) found that Spanish SMEs were able to adopt more proactive internationalization strategies if the decision-makers had in-depth knowledge of foreign markets and the capacity to develop business relationships in foreign languages. Similarly, Sui et al. (2015) studied immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada and identified the importance of foreign language knowledge in the selection and pursuit of overseas markets. Yan et al. (2018) studied Chinese SMEs and found that language barriers created challenges for SMEs when communicating with foreign customers. Similarly, Stoian et al. (2011) found that foreign language proficiency has a strong positive influence on export success and plays a key role in facilitating the penetration of foreign markets and improving the ability of doing business with overseas clients. Consistent with these previous examples, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 1g. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when the CEO has foreign language ability.

As underscored by Verbeke et al. (2014), entrepreneur’s characteristics function as firm-specific advantages. As described earlier, education level, immigrant status, international and previous start-up or industry experience have been identified in the literature individually as CEO’s characteristics that have an association with SMEs’ internationalization. Therefore, we can expect that the combination of these CEO’s characteristics would have a positive relationship with the firm’s internationalization. Accordingly, Hypotheses 1a through 1g focus upon CEO characteristics and internationalization.

2.2. Firm Characteristics

There are several IB theories that explain how firms expand internationally. One of these theories is the internalization theory, which is the general theory of the firm, with conceptual foundations derived from three fields: resource-based view (RBV) thinking, transaction cost economics (TCE), and entrepreneurship (Verbeke et al., 2014; Verbeke & Ciravegna, 2018). The combination of these three views is particularly useful in examining the international expansion of SMEs, where the founder is the one making decisions on allocating limited resources in order to create value by capturing markets abroad (Coviello, 2015). Verbeke et al. (2014) suggested that future research on international expansion using the internalization theory should include characteristics of founding entrepreneurs in addition to traditional economic activities identified as firm-specific advantages (FSAs). Thus, examining both should give a more complete picture of SMEs FSAs endowments. Therefore, we focus on the firm’s characteristics next.

According to the Uppsala model of internationalization, SMEs lack the capacity, efficiencies, and economies of scale needed to extensively engage in exporting (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977, 2009). On the other hand, larger and more established firms are better able to cope with the associated increase in operational demands (Clegg, 2018). As SMEs grow, they are able to start accumulating resources and provide the funding levels needed to support their exporting efforts compared with much smaller firms (Bonaccorsi, 1992; World Trade Organization, 2016). Additional funds allow SMEs to better address the risks and challenges of exporting.

Similarly, company size in terms of the number of employees has also been identified as a constraint, having more employees with greater expertise would allow SMEs to be more successful exporters (Bilkey & Tesar, 1977; Ruzzier & Ruzzier, 2015). Others have also used the firm’s total annual gross sales to operationalize firm size (Jantunen et al., 2008). Firm size has been operationalized by either using the number of employees, or total annual sales, or both. According to Ruzzier and Ruzzier (2015), export marketing, and IB literature support the view that firm size, as a reflection of the number of employees and sales, is positively related to export intensity and is a distinguishing factor between internationalized and non-internationalized firms. As described above due to the traditional constraints experienced by SMEs, entering foreign markets quickly can also be a challenge. Consequently:

Hypothesis 2a. SMEs with larger start-up capital are more likely to internationalize.

Hypothesis 2b. SMEs with more employees are more likely to internationalize.

Hypothesis 2c. SMEs with larger total annual sales are more likely to internationalize.

Contrary to these views, the literature of rapidly internationalizing SMEs suggests that young firm’s flexibility helps them to internationalize early. Scholars have argued that this can be achieved due to the reduction in costs of the change brought about by internationalization as perceived by the firm’s top management (Shrader et al., 2000). Furthermore, young firms learn faster and acquire knowledge more quickly than older firms and can therefore internationalize sooner (e.g., Autio et al., 2000). In other words, young firms experience less risk in international expansion and can internationalize faster than older firms (Autio et al., 2000). Scholars have found that even though firms could potentially enter markets rapidly this could have an adverse impact on their performance (e.g., Musteen et al., 2010). Consistent with this argument:

Hypothesis 2d. SMEs are more likely to internationalize when they are younger.

Figure 1 presents the overall research model and highlights the independent variables, the dependent variable and the hypotheses associated with CEO and firm characteristics.

3. Methods

3.1. Samples and Data Collection

3.1.1. SBO (archival) data

To test the hypotheses, two independent datasets were used. The archival (secondary) data was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau while the primary data was collected by the authors through an online survey. The Survey of Business Owners (SBO) conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau was identified as an appropriate data source and is collected every five years, for years ending in 2 and 7; as part of the economic census and has been used in prior SMEs studies (Heileman & Pett, 2018). Companies selected to participate in the survey are required to do so by law (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). The first-ever SBO Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) was made available for the 2007 survey and to date, no additional SBO PUMS was released. To protect the confidentiality of individuals and businesses, the PUMS file provides rounded, noise-infused estimates of receipts, payroll, and employment.

The initial SBO sample contained 60,570 SMEs from California. However, after the employment size was set between 10 and 500 employees the sample was reduced to 14,519 SMEs. Since the purpose of the study was to test the characteristics of the CEO, a decision was made to only examine businesses that have one owner and that the business was actually founded by the owner rather than inherited or purchased. Once these additional criteria were applied the sample was further reduced to 2,240 SMEs.

3.1.2. Survey (primary) data

Since the SBO data did not have all the variables needed to test the hypotheses presented, primary survey data was also required. To accomplish this, an online survey instrument was used to collect the data needed to answer the research questions and test the hypotheses. The survey questions were similar to the U.S. Census SBO with additional questions based on previous studies.

A random sample of California SMEs with contact information was obtained from the Infogroup Business Email Database. The responses were collected using Qualtrics from August 2016 through April 2017. The survey was emailed to 3,000 contacts and 354 completed the survey for a total response rate of 11.8 percent. Due to missing or incomplete data, 329 of the responses were usable for analysis. Even though the response rate was lower than anticipated, the number remained adequate to carry out meaningful analyses.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in the SBO dataset was whether a firm generated any sales outside the U.S. The responses were coded into a dichotomous variable (non-exporting and exporting). Similarly, the outcome measure of interest from the survey was measured by asking individuals if they currently have any exporting activity.

3.2.2. Independent Variables (IVs)

The IVs in the SBO (archival) dataset included education, immigrant status, previous start-up experience, start-up capital, and the number of employees. The IVs from the survey dataset included the firm’s age, annual sales, number of employees, CEO’s education level, the experience of studying/living/working abroad, immigration status, start-up and industry experience, and foreign language ability. Tables 1 and 2 provide the list of variables included in the research model, where the data was obtained from, and subsequent coding protocols.

Because of the two samples and the number of hypotheses tested, Table 3 is provided as a summary. More specifically, Table 3 includes the hypotheses and the data sources used to conduct the relevant analyses.

3.2. Statistical Method

Unlike most previous SMEs studies that investigate firm internationalization by limiting their analysis only on firms that are already international, this study included both non-internationalized and internationalized firms. This is an important distinction because it allows us to treat the act of internationalizing as a variable to understand, rather than as a defining property of the SMEs examined. Logistic regression has been used by researchers using categorical outcomes (cf., Hessels & Terjesen, 2010; Orser et al., 2010; Verbeke et al., 2014) in the extant literature. When dichotomous variables are used as the dependent variable, logistic regression is also the analytical tool of choice (Hair et al., 2010) due to the violations to the assumption of regular ordinary least squares (OLS) regression which make using OLS regression problematic in this case. Consequently, for all of the hypotheses across both data sets presented in this study, logistic regression is used to determine whether the variables examined are associated with the dichotomous outcome of whether an SME internationalizes or not (Hair et al., 2010).

4. Results and Analysis

Tables 4 and 5 provide the descriptive summary and correlations for the two datasets. Because the variables in both tables are categorical, Spearman’s rho is reported. From these two tables, a few interesting patterns appear. First, the proportion of SMEs that internationalized was much lower in the SBO data than in the primary survey data. More specifically, only 15% of the firms in the SBO data had internationalized whereas 55% of the firms in the survey data had done so. In addition, the absolute magnitude of the relationships with internationalization was significantly higher in the survey data, while no measure was associated with internationalization in the SBO data to a degree of more than .09.

A logistic regression model containing five predictors from the SBO dataset (education, immigrant status, previous start-up experience, amount of start-up capital, and number of employees) was calculated to assess the impact of these factors on the likelihood that SMEs would report that they are exporting. The full model was statistically significant, χ2 (5, N=2,240) = 24.21, p < .001, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between SMEs which exported and those that did not. The model explained between 1.1 percent (Cox and Snell R square) and 1.9 percent (Nagelkerke R squared) of the variance in exporting, and correctly classified 84.7 percent of the cases. As shown in Table 6, only two of the variables made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model (education and immigrant status). The strongest predictor of SMEs exporting was immigrant status recording an odds ratio of 1.60. This indicated that SMEs whose owners are immigrants were 1.6 times more likely to export than those who were not immigrants, controlling for the other factors in the model. Similarly, the odds ratio of 1.35 for college education also indicated that owners who were college-educated were 1.35 times more likely to export.

When using the SBO data, the results from the logistic regression analysis indicate that the proposed model had significant predictive power in determining if certain FSAs positively predict if an SME is exporting. However, only two factors were statistically significant. Due to the limitations of the SBO data with regard to the CEO’s characteristics, primary data were also collected and analyzed.

To address the limitations of the SBO data, survey data developed specifically for this study was also analyzed. The survey data collection instrument was slightly different from the U.S. Census Bureau SBO data, however, the variables were kept similar to the SBO data. Further, more granular analyses were possible due to the lack of noise and company-shielding that was present in the SBO data.

For the subsequent analysis, logistic regression was used once again due to the dichotomous nature of the internationalization measure. These results are presented in Table 7.

The full model containing all predictors was statistically significant, χ2 (10, N = 329) = 83.84, p < .001, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between SMEs that exported and those that did not. The model explained between 22.5 percent (Cox and Snell R square) and 30.1 percent (Nagelkerke R squared) of the variance in exporting, and correctly classified 69.6 percent of cases. The strongest predictor of SMEs exporting was worked abroad experience recording an odds ratio of 2.60. This indicated that SMEs whose owners had prior experience of working abroad were 2.6 times more likely to export than those who did not have that experience, controlling for the other factors in the model. Similarly, the odds ratio of 2.41 for college education also indicated that owners who were college-educated were 2.41 times more likely to export.

5. Discussion

This section presents a discussion of the results in the context of previous literature and assesses the effects of the results on the proposed objectives and tested hypotheses. The results of the hypotheses testing are presented in Table 8.

Results from Tables 6 and 7 indicate that various founder and firm characteristics have a strong association with SMEs internationalization. Specifically, the results confirm that hypotheses H1a (education), H1f (worked abroad), and H2c (total annual sales), all are strongly associated with SMEs internationalization, while hypotheses H1b (immigration) and H2b (number of employees) were partially supported.

Our support of H1a is aligned with previous findings of a positive relationship between college-educated founders of SMEs and their propensity to export (Ganotakis & Love, 2012; Stucki, 2016). A higher level of education is not only a source of a higher level of knowledge, but it enables entrepreneurs to develop transferable skills including improved problem solving, organizing, sensing, and sizing opportunities. The study also found that besides the founder’s educational level, their immigrant status (H1b), and previous work abroad experience (H1f) were positively associated with whether a firm will be internationalized or not. Several other authors have linked the founder’s immigrant status to their success as exporters (cf. Drechsler et al., 2019; McDougall et al., 1994). One of the plausible explanations is that immigrant entrepreneurs have access to valuable networks due to their personal relationships in markets abroad (Drechsler et al., 2019; McDougall et al., 1994).

Even though our results did not find support for hypotheses H1c (start-up experience), H1d (industry experience), H1e (studied/lived abroad), and H1g (foreign language) our results did support hypothesis H1f (work abroad). Similar to the benefits of being an immigrant, working abroad can provide decision-makers with an in-depth knowledge of foreign markets and the opportunity to further nurture and develop their relationships overseas. This finding is significant because it allows founders to leverage their networks while also creating a global vision for their firm. These experiences and knowledge also allow firms to minimize the uncertainty (thereby reducing the liability of foreignness) and take advantage of potential opportunities abroad (D’Angelo & Presutti, 2019).

When examining the results regarding the association of a firm’s characteristics and internationalization we find support for hypothesis H2c (total annual sales) and partial support for H2b (number of employees). Both of these findings are in line with previous arguments that having more employees with greater expertise would allow SMEs to be more successful exporters (Bilkey & Tesar, 1977; Ruzzier & Ruzzier, 2015). According to Ruzzier and Ruzzier (2015), export marketing and international business literature support the view that firm size, as a reflection of the number of employees and sales, is positively related to export intensity and is a distinguishing factor between internationalized and non-internationalized firms. Contrary to the findings in the international entrepreneurship literature, our results did not find support that firm’s age has an impact on firm’s internationalization (H2d). We also did not find support for the association between the amount of startup capital (H2a) and firm internationalization. Consequently, of the four firm characteristics we examined, only two (total annual sales and the number of employees) were associated with a firm’s internationalization.

6. Conclusion and Contributions

The objective of this paper was to examine empirically whether a set of founder personal characteristics and firm attributes are associated with the internationalization of SMEs. Using two different data sets of California SMEs (i.e., the SBO data and survey data collected specifically for this study), the study addressed the research gaps identified by Cavusgil and Knight (2015), Verbeke et al. (2014), and Tsao et al. (2018) and their recommendations to further investigate factors associated with the internationalization of SMEs on large samples in advanced economies.

Our results support the hypotheses that founder’s educational level, work abroad experience, and immigrant status are positively associated with the internationalization of SMEs. Moreover, the firm’s size measured in total annual sales and employee headcount were also positively associated with the internationalization of SMEs. Based on the results of the study, future entrepreneurs who are interested in pursuing internationalization should determine if they or someone on their team possesses the characteristics identified in this study. This would give them an indication of how likely it will be for their firm to internationalize and what steps they could take to make their goal of internationalizing their firm a reality. Founders should pay attention to education’s role and seek to enhance their own capacity as well as that of their employees through funding and supporting specialized education and training. Close collaborations with local educational institutions, local government, and industry bodies would provide opportunities to access relevant knowledge, as well as advocate for the provision of required training and people development.

For existing firms, hiring individuals with these qualities could potentially enable them to pursue their internationalization expansion sooner or give them confidence that they would be able to achieve their international expansion goals. SMEs could target expatriates who might be willing or interested in joining a smaller firm upon their return home. Close collaboration with local colleges and a well-defined people development strategy could also be a strong advantage in attracting and retaining talent particularly in a very competitive labor market. Furthermore, given the significant relationship between higher level of education and the likelihood for an SME to internationalize, government policies can provide targeted incentives and support to the university graduates to set up their own businesses and create jobs rather than seek employment with established companies. Additionally, being able to identify SMEs that are more likely interested in, and successful at, internationalizing their businesses would make various export assistance programs and initiatives more efficient and effective in reaching their goals.

This study makes several contributions to the existing literature by integrating the perspectives of upper echelons and internalization theories, and testing the proposed model on two large samples of SMEs in order to identify what entrepreneur and firm characteristics are associated with SME internationalization. In summary, the results allow us to conclude that firm’s internationalization is influenced by several founder’s characteristics such as education, immigrant status, work-abroad experience, and firm-specific characteristics such as size, measured by the number of employees and total sales. Since internationalization is a desirable goal for SMEs as well as the economy in which the company operates, we hope that the results and implications of our study will be stimulating to future scholars in order to further examine factors influencing SMEs internationalization.

6.1. Limitations

Even though the findings in this study have validated previous research and have provided some new insights and contributions there are several limitations that need to be acknowledged. The SBO data included a relatively narrow set of variables. In addition, there was a 10-year time difference between the SBO data, and the survey data collected for this study. This time difference made it difficult to determine if certain differences in the results were due to this or other factors.

6.2. Directions for Future Research

This study only examined the CEO’s individual characteristics and did not make a distinction if multiple individuals founded or managed the firm. Future research could examine the traits of the founding team members. This would provide additional insights into the effects these individuals have on the internationalization process of SMEs. Examining the top management team more closely could further help explain the differences between different levels and types of SMEs’ internationalization (Coviello, 2015; Coviello et al., 2017). Studying the entire top management team of the firm would also help with triangulation and to minimize errors.

Future studies could adopt the framework presented in this study and incorporate other elements to generate additional insights on the relationship of these factors to SMEs’ internationalization. Scholars could expand the model by studying additional CEO characteristics, personal and social networks, investigating environmental and country-specific factors, and integrating business models along with additional firms’ characteristics.

Incorporating the external environment and country-specific advantages would be another area to extend this research further since this study did not take these into account. Studies have also identified that location influences the export performance of SMEs (Freeman et al., 2012). Their study of SMEs in Australia found that firms in metropolitan areas have an advantage over those firms in remote areas due to access to networks and export-related infrastructure and services (Freeman et al., 2012; Freeman & Styles, 2014).

Future studies could also incorporate questions about the various types of export assistance programs and to what extent these firms are aware or take advantage of these opportunities and resources. Moreover, replicating this study in a different geographic context could provide additional insights whether this study’s findings are due to county-or region-specific effects.