Introduction

Goal misalignment is one of the primary causes of conflict within the franchisor-franchisee dyad. While both parties share a common goal of wealth creation, franchisors and franchisees often emphasize different priorities and exhibit widely diverging behaviors (Dada, 2018; Winsor et al., 2012). Indeed, the selection of qualified franchisees is considered one of the most critical decisions franchisors make, because franchise organizations’ financial performance may be contingent on the “fit” between the franchisee and the franchisor (Clarkin & Swavely, 2006). Franchise opportunities, particularly business-format franchises, are typically marketed as turnkey businesses such that franchisees need relatively little prior experience because they are essentially purchasing the right to operate a proven business model. Thus, franchisors should naturally gravitate to potential franchisees who reflect a certain psychological profile—one that includes the willingness to follow and execute an established plan. However, empirical research on the efficacy of franchisee autonomy is inconclusive (Dada, 2018; Pardo-del-Val et al., 2014; Pizanti & Lerner, 2003; Watson et al., 2016). While compliance helps ensure standardization and consistency across the franchise network and reduces the likelihood of opportunistic and shirking behaviors, greater franchisee independence may enhance network-wide adaptability and innovation.

The current study seeks to address this apparent paradox by heeding the call from Combs, Ketchen, and Short (2011) and other scholars (e.g., Dada et al., 2010; Dant et al., 2013) for additional research focusing on the micro-level processes and outcomes of the franchisee-franchisor relationship. They suggest that further identification and assessment of specific personality characteristics are needed to develop a more robust view of franchisee-franchisor interactions and outcomes. Grounded in self-determination theory (SDT), we examine the interplay between three general franchisee dispositional constructs—the desire for autonomy, personal initiative, personal self-awareness—and individual franchise unit financial performance. We contend that a franchisee’s desire for autonomy generally impedes a productive franchise arrangement because of the conformity requirements imposed by the franchise agreement. SDT postulates that autonomy is a primary driver of motivation, but allegiance to a standard set of operating procedures is necessary for a successful franchise relationship. Consequently, franchisees who exhibit a strong appetite for independence may be less motivated and underperform as franchise operators than their more compliant peers. However, we also demonstrate that a franchisee’s initiative and self-awareness act as suppressing variables (MacKinnon et al., 2000) between desire for autonomy and franchise performance.

We also contribute to the franchising and entrepreneurship literature by explicitly examining the relationship between an individual’s desire for autonomy, one of the basic psychological needs identified in SDT (Legault, 2020), and objective financial performance. Our understanding of a franchisee’s personality implications, including a desire for autonomy, is limited because the primary focus of extant literature is the quality of the franchisee-franchisor relationship (Crosno & Tong, 2018; Mignonac et al., 2015). While a few empirical studies have addressed financial outcomes, they are most often reliant on subjective self-report performance measures (Colla et al., 2019; Combs, Ketchen, Shook, et al., 2011; Dada, 2018; Watson et al., 2020).

Literature Review

The success of any franchise system depends, in large part, on an effective screening process to ensure the selection of suitable franchisees who will operate the franchisor’s business system. Franchise ownership is commonly assumed to be equivalent to owning an independent small business, and most franchise promotional material emphasizes the entrepreneurial aspects of franchise opportunities. This messaging suggests that many franchisors seek to recruit individuals that display characteristics commonly associated with successful entrepreneurs, such as the need for achievement, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and locus of control (McGee & Peterson, 2019; Watson et al., 2020).

Evidence suggests that franchisees do exhibit entrepreneurial traits, and franchisors intentionally recruit individuals with those dispositional characteristics (Boulay & Stan, 2013; Dada et al., 2015; Leopold & Kasselmann, 2002; Soontiens & Lacroix, 2009; Watson et al., 2020; Zachary et al., 2011). While recruiting entrepreneurial-minded individuals to be franchisees is appealing on the surface, the selection decision is far more complicated and fraught with risk (Clarkin & Swavely, 2006). Normative prescriptions for identifying the most critical personality characteristics are limited because empirical research has produced inconclusive and often contradictory results. Some scholars argue that franchisees should be viewed as independent entrepreneurs and provided with autonomy and the freedom to innovate (e.g., Evanschitzky et al., 2016). In contrast, other scholars contend that franchisees should conform and be willing to follow the franchisor’s strict formula (Blair & Esquibel, 1996). Indeed, some experts claim the behaviors of successful franchisees are more similar to managers than independent entrepreneurs (Falbe et al., 1999; Ketchen et al., 2011).

Desire for Autonomy

The desire for autonomy refers to an individual’s preference for independence from restrictive environments. Self-determination theory (SDT) posits that this personal disposition along with competence and relatedness represent fundamental psychological needs for personal growth, well-being, and motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Kovjanic et al., 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Van den Broeck et al., 2016). According to SDT, differences in an individual’s personality and behavior result from varying degrees to which each of these needs has been satisfied or suppressed (Deci & Ryan, 2008). When people feel autonomous, they perceive greater freedom to make their own decisions, generate their own ideas, and set their own goals. Moreover, a sense of autonomy allows individuals to feel like they maintain control of their actions and possess the ability to pursue their interests and values. Thus, SDT is particularly useful in describing how social-contextual factors influence the development of autonomy and the resulting higher sense of well-being and motivation.

Entrepreneurial autonomy refers to a business owners’ right to decide what work is done, and when and how it is done (Gelderen, 2016). As such, individuals exhibiting this disposition tend to spurn the rules and regulations imposed by established organizations (Rauch & Frese, 2007). Not surprisingly, the desire for autonomy is one of the most common reasons people start their own business, because the sense of independence allows them to embrace and pursue their passions and determine their own actions (Alstete, 2008; Carter et al., 2003; Feldman & Bolino, 2000; Wilson et al., 2004). Moreover, the desire for autonomy is not limited to nascent entrepreneurs, because the sense of independence is also a dominant source of satisfaction for existing small business owners (Benz & Frey, 2008a, 2008b; Hundley, 2001; Lange, 2012; Prottas, 2008; Schjoedt & Shaver, 2012).

The benefits of granting entrepreneurial autonomy to franchisees in specific situations are well documented (Dada, 2018). Autonomy can serve as a mechanism to create value for the franchisor by identifying local market trends, uncovering cost efficiencies, and fostering other system-wide improvements (López-Bayón & López-Fernández, 2016). Franchisors create the initial business concept and rely on franchisees to play a critical role in identifying new technical innovations, market trends, and market opportunities. For instance, Flint-Hartle and de Bruin (2011) reported that real estate brokerage franchisees introduced several novel innovations such as online marketing enhancements, improved auction initiatives, and shared databases embraced throughout the entire franchise system. Greater franchisee autonomy appears particularly beneficial when appropriate governance systems are in place, and potential agency problems are less of a concern (Cochet et al., 2008).

While franchisee autonomy may be advantageous in certain situations, the typical franchise system is based on replicating a prescribed business model. Indeed, adherence to a proven formula is the cornerstone of successful franchising. Consequently, individuals with a strong desire for independence and autonomy may be less than ideal franchisees. Moreover, several experts claim that franchisees are not “real” entrepreneurs (Dada et al., 2015). Rather than displaying high levels of achievement motivation, a desire for self-actualization, and independence, franchisees tend to be more concerned with stability, security, and risk-aversion (Anderson et al., 1992). Similarly, Sardy and Alon (2007) reported that franchisees possess less confidence in their abilities to succeed than independent entrepreneurs.

According to SDT, this desire for independence and self-direction is inherently innate (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Individuals instinctively aim to have this need satisfied if the environment supports these aims. This implies that although the need for autonomy is present in everyone, it requires environmental support to truly influence an individual’s behavior and actions. Individuals placed in an environment that fails to support autonomy tend to be less motivated because of the inability to reach their full potential. The requisite allegiance to a strict set of operating procedures often represents such an environment.

In summary, most franchising systems’ rigidities may be appealing to individuals who are willing to forfeit a certain level of autonomy to own a proven business model. Franchisees can enjoy business ownership while benefiting from the infrastructure provided by the franchisor. This arrangement should be particularly appealing to individuals who may lack confidence in their abilities to manage an independent business. In contrast, individuals who exhibit a greater desire for autonomy may find the franchising arrangement overly restrictive and unsupportive. Thus, while a franchising system may provide a blueprint for success, the limitations inherent in most franchising arrangements may be suffocating to individuals who desire the ability to act independently. Hence, we predict:

H1. A franchisee’s desire for autonomy is negatively related to franchise unit financial performance.

Personal Initiative

While we predict that a franchisee’s desire for autonomy may be detrimental to overall franchise financial success because it impedes an individual’s willingness to follow a franchisor formula, we expect that a franchisee’s initiative may suppress this potentially adverse relationship. Personal initiative (PI) refers to being a persistent, future-oriented, proactive self-starter (Rank et al., 2004). Individuals with high initiative demonstrate a willingness to overcome perceived barriers and achieve their goals despite a lack of resources and support (Mensmann & Frese, 2019). PI is also associated with a heightened motivation to succeed (Frese & Gielnik, 2014) and greater preparedness to respond to a changing and uncertain business environment (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006). In addition, demonstrating PI helps entrepreneurs proactively identify future threats and opportunities (S. K. Parker et al., 2010), to experiment (Frese & Gielnik, 2014), and to persist when confronting obstacles (Frese & Fay, 2001). As such, PI is generally viewed as a critically important behavior for entrepreneurs because it contributes directly to business success (Campos et al., 2017; Glaub et al., 2014; Hahn et al., 2012).

Similarly, PI appears in an individual’s proactive personality (Frese & Fay, 2001). As noted by Seibert and colleagues (2001), a “proactive personality is a stable disposition to take PI in a broad range of activities and situations” (p. 847). Individuals with a proactive personality display initiative by scanning for opportunities, taking action, and remaining persistent until they achieve their desired goals (Bateman & Crant, 1993). Rauch and Frese (2007) contend that successful entrepreneurs need to possess a proactive personality and exhibit PI. Indeed, they argue that the need to be a self-starter and act on available opportunities is fundamental to entrepreneurship. The authors also reported a significant, positive association between PI and small business success as defined by longevity.

PI is generally considered a marker of the psychological growth that humans seek according to SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000). This personal disposition allows an individual to remain optimistic when environmental resources and support needed for personal growth and well-being are lacking. PI also represents an intermediary mechanism through which the desire for autonomy is channeled. Control over one’s job has been shown to stimulate PI by providing opportunities for greater responsibility, enhanced self-confidence, and a general sense of increased competence (Frese & Fay, 2001; Hornung & Rousseau, 2007; Ohly et al., 2006). Autonomy appears to serve as an antecedent to higher levels of initiative and proactive behaviors (Hornung & Rousseau, 2007; S. K. Parker et al., 2006, 2010). Moreover, the literature indicates that PI mediates the relationship between job autonomy and psychological well-being (Yang & Zhao, 2018).

In summary, PI is viewed as a universally desirable trait in most contexts (Cerasoli et al., 2014). We contend that this dispositional characteristic is particularly beneficial to franchisees because it serves as an intermediary mechanism to suppress the negative relationship between a franchisee’s desire for autonomy and financial performance. In other words, the franchisee’s counterproductive appetite for independence is channeled through their inclination to overcome a lack of resources and support and other challenges. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2. A franchisee’s personal initiative mediates the negative relationship between the franchisee’s desire for autonomy and financial performance.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness (SA) is another critical dispositional characteristic that helps channel a franchisee’s counterproductive yearning for autonomy into desirable behaviors. It reflects how individuals recognize and respond to various obstacles and challenges based on understanding their strengths and weaknesses. As Ingram and colleagues note, SA serves as an entrepreneur’s emotional regulator when addressing uncertainties that arouse emotion (Ingram et al., 2019). As such, more self-aware individuals should enjoy a broader attention scope, broader behavioral repertoires, and more flexible behaviors (Fredrickson & Losada, 2005). In addition, a heightened SA should bolster cognitive processing (May et al., 2004), affect decision-making (Isen & Labroo, 2003), and aid in problem-solving (Schutte et al., 2001). Enhanced SA also increases social support networks by nurturing the ability to develop better relationships with others (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

SA may be particularly pivotal for franchisees within the constraints of a franchising arrangement. Effective franchisees need to exhibit the appropriate behaviors to successfully manage their franchise units while simultaneously adhering to the franchisor’s strict business template. The tension between the desires of the franchisee and the franchisor’s expectations runs counter to the SDT prescription that individuals need access to resources and support for autonomy to manifest into increased motivation and well-being (Legault & Inzlicht, 2013; Vallerand et al., 2008). However, research focusing on the behavioral aspects of an individual’s ego provides insight into how some people overcome this apparent contradiction (Huffman et al., 2015; Niemiec et al., 2008; Wayment et al., 2015). A “quiet ego” refers to a self-identity fostered through purposeful reflection, awareness, and viewing the world from multiple perspectives. A quiet ego is characterized by compassion and self-regulation. This self-identity enables individuals to suppress counterproductive self-centered impulses and strive for a greater sense of overall well-being. Individuals with a quiet ego calibrate their own thoughts, feelings, and intentions to better align with those of others. As opposed to a “noisy ego”, a quieter ego plays an influential role in effective adaptation and conflict resolution.

In summary, franchisees who exhibit greater SA should be better able to appreciate and adapt to the limits imposed by the franchise arrangement. We predict this personal disposition serves as a mediator between an individual’s desire for autonomy and financial performance. Specifically, we contend that successful franchisees with a healthy thirst for independence may underperform within a franchise arrangement unless their SA dampens their impulse to engage in entirely self-centered behaviors. In other words, SA serves as a conduit to suppress the potential detrimental impact of a franchisee’s desire for autonomy. Hence:

H3: A franchisee’s self-awareness mediates the negative relationship between the franchisee’s desire for autonomy and financial performance.

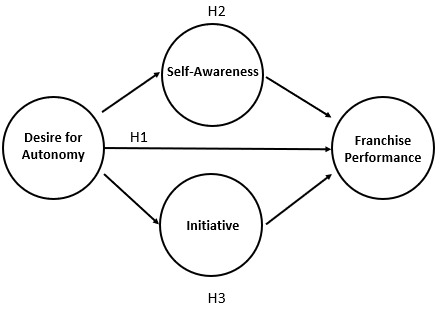

Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized relationships.

Methods

Data and Sample

We obtained the data from a commercial franchisee profiling organization that conducts potential franchisee fit assessments using a proprietary aggregation of numerous widely recognized constructs. The focal dataset for this project includes demographic and psychographic information on individual franchisees, the franchise location, the average number of members at the location, the number of years the location has been open for business, and financial performance data. The initial sample consisted of 335 individual fitness centers in the United States. Our sample was reduced to 274 fitness centers after omitting observations with missing values.

Measures

Independent variables. Three constructs containing three items each were adapted for the study— desire for autonomy (α = .684), initiative (α = .703), and personal self-awareness (α = .656). While the reliabilities are not what we would expect for traditional research, the profiling organization created the construct scales using their proprietary assessment tool. However, the items are very similar to existing validated scales. For example, the three items measuring initiative (“I pursue goals beyond what’s expected of me,” “I cut through red tape and bend the rules when necessary to get the job done,” and “I mobilize others through unusual, enterprising efforts” mirror the items developed by Frese and colleagues (1997) that include “usually I do more than I am asked to do” and “I use opportunities quickly in order to attain my goals.” The scale for self-awareness (“I’m aware of my strengths and weaknesses,” “I’m reflective and learn from experience,” and “I’m open to candid feedback, new perspectives, continuous learning, and self-development”) are very similar to other self-awareness scale items including those reported by Ashley and Reiter-Palmon (2012) such as “to what extent would your friends describe you as someone who knows themselves well,” “how often do you ponder over how to improve yourself from knowledge of previous experiences,” and “to what extent have you used feedback from your professor or boss to improve your performance.” The measure for a desire for autonomy includes “I can voice views that are unpopular and go out on a limb for what is right,” “I’m decisive, able to make sound decisions despite uncertainties and pressures,” and “I have courage that comes from certainty about my capabilities,” which are very similar to existing measurement instruments such as the scale developed by Dant and Gundlach (1999) that includes "I prefer the opportunity for independent thought and action,, “I prefer to receive a lot of guidance from my franchisors (R),” and “I prefer to work independently of others”. Table 1 provides a comparison of items in each measure.

Dependent variable. Franchise performance was measured as the total income received from personal training services for each fitness center. Personal training income is a superior measure of the direct effects from franchisee attributes than other financial performance metrics such as membership dues. While membership dues can be a reflection of the franchisor’s brand awareness and marketing efforts that draw potential members to the fitness center, personal training services are generally added after members have joined and are primarily driven by the sales and marketing efforts of the individual franchisee.

Control variables. We included the average total number of members and the number of years each location has been open as control variables. The average number of members accounts for variance in the total number of members across locations. The total years open accounts for variance in revenues due to longevity.

RESULTS

Table 2 summarizes descriptive statistics and correlations between all the variables in our model.

We tested our hypotheses using the Preacher and Hayes (2008) multiple mediation method and employed bootstrapping to correct its inherent procedural flaws. This technique allows us to retest our mediation mechanisms in thousands of subsamples derived from a nonparametric resampling procedure which generates confidence intervals that do not rely on the assumption of normality in the sampling distribution. As a result, this method provides more robust and accurate estimates of mediation effects. We chose this particular methodology because of the nature of the data. We were unable to develop scale items ourselves and had little control over the measures’ reliability and how the individual items loaded onto their respective constructs. The multiple mediation technique (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) allowed us to examine our hypothesized relationships without forcing the high levels of measurement reliability and strong factor loading values often required by other methodologies.

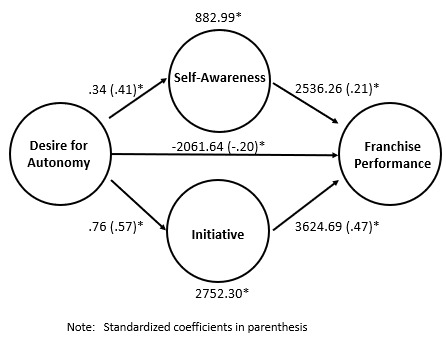

We initially analyzed our proposed mediating mechanism, including the control variables mentioned above, and the results revealed that both components of our multiple mediation model were significant. The total number of members was the sole statistically significant control variable. Next, we repeated the analyses with the control variables removed. This step was undertaken because mediation effect sizes become impossible to estimate with the introduction of control variables into a multiple mediation analysis (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). A visual representation of the hypothesized model’s results is presented in Figure 2. The significance of the overall effect, the direct effect, the mediators, and estimations of the confidence intervals for the effects of each are represented in Table 3.

As presented in Table 3, the relationship between the desire for autonomy and performance is negative and significant (p < .05). Thus, H1 is supported. Additionally, the parallel mediation effects of self-awareness and initiative on performance are both positive and significant (p < .05) providing support for H2 and H3. Since the mediating variables are positive while the direct relationship is negative, initiative and self-awareness essentially serve as suppressing variables on the direct relationship (MacKinnon et al., 2000). In assessing the relevance of the effect sizes found in our mediation analysis, we utilized the benchmarks set by Preacher and Kelley that define small, medium, and large effect sizes as .01, .09, and .25, respectively (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). In evaluating our effect sizes against this standard, we find our effect sizes (represented in parentheses found in Table 3) approach a moderate size for the self-awareness mechanism (β = .09, p < .05) and exceed a large size for the initiative mechanism (β = .27, p < .05).

Discussion

Contributions to Entrepreneurship Research

The results of this study contribute to the continuing debate about the role that franchisee independence plays in the franchisee-franchisor relationship. We were most eager to examine how a franchisee’s desire for autonomy impacts financial performance and how much of that relationship flows through personal initiative and self-awareness. Our findings suggest an individual’s need for independence may be counterproductive to a successful franchisee-franchisor dyad because a franchisee’s desire for autonomy was, in fact, negatively related to performance. However, we discovered that this negative effect may be suppressed if the franchisee’s appetite for independence is channeled through their heightened self-awareness and personal initiative. In other words, an individual’s willingness to receive feedback and a demonstrated motivation to excel may ease the potential tension created by a franchisee’s desire for autonomy.

The typical franchise system is designed around a standardized business format that facilitates consistency, efficiency, and quality control. Indeed, maintaining uniformity across the system is often considered one of the most critical elements of franchising because it ensures customers share a common experience across the franchise network (Pardo-del-Val et al., 2014). Uniformity also helps protect the brand image and reduce costs through economies of scale and the application of standard operating procedures. However, such a system makes it challenging for a franchisee with an appetite for autonomy to flourish because they are reduced to simply executing standardized practices and procedures established by the franchisor. A paradox is inevitably created because franchises are often marketed as opportunities for individuals to become their own boss, yet departures from the franchise format are discouraged. Thus, tensions arise between the franchisors’ desire for conformity and the franchisee’s desire for autonomy and independent decision-making.

Agency theory has long served as the primary lens through which to view the franchisee-franchisor relationship. Still, several scholars have acknowledged this approach’s limitations and suggested that alternative theories are needed (Combs, Ketchen, Shook, et al., 2011). We join this conversation by drawing on self-determination theory to offer further insight on how best to harness a franchisee’s desire for independence. Franchisee autonomy has been linked to various system-wide improvements such as the development of technical innovations and identification of market opportunities (Flint-Hartle & De Bruin, 2011; López-Bayón & López-Fernández, 2016). However, much of the research in this area has focused on mechanisms to minimize potential agency problems such as incentive programs, organizational structures, and governance systems (Cochet et al., 2008; Colla et al., 2019; Dada, 2018). The role personal dispositions play in the franchisee-franchisor relationship has received much less attention (Combs, Ketchen, Shook, et al., 2011; Croonen et al., 2016; Dant et al., 2013; Evanschitzky et al., 2016; S. L. Parker et al., 2018). Our results highlight the importance of appropriately assessing a franchisee’s desire for autonomy, personal initiative, and self-awareness.

Managerial Implications

Selecting the right franchisee is one of the most pivotal decisions a franchisor faces, and psychological profiling can be a valuable tool in the decision-making process. Our results inform franchisors about the desirability of franchisees who demonstrate an appetite for independence. A desire for autonomy, for example, might be linked to opportunistic behavior by franchisees, so franchisors should more fully consider how to select potential franchisees and assess future transaction costs. These results complement findings in other studies that a desire for autonomy may be appealing because potential franchisees exhibiting such attributes may engage in behaviors that tend to advance the franchise system as a whole without primarily seeking their self-interests and exhibiting free-riding tendencies (Colla et al., 2019; Dada, 2018). Our findings demonstrate that a franchisee’s preference for independence is generally only beneficial when they are ambitious and exhibit a drive to succeed. Equally important, franchisees who prefer autonomy must be willing to accept feedback and respond accordingly.

Our findings also suggest that franchisors can bolster their franchise performance by providing training for franchisees with a strong desire for autonomy. Training opportunities to help nurture proactive initiatives and to enhance self-awareness can serve to ease the negative effects that a yearning for independence can have on a franchisee’s financial performance. Franchisors can also provide clear guidelines and communication regarding areas where franchisees can be more creative and innovative within the system and where they cannot. Such actions can help franchisors effectively harness the efforts of those franchisees who express a strong desire for autonomy.

Conclusion and Directions for Future Research

This study has several limitations, including our use of a dataset provided by an organization dedicated to analyzing franchisor-franchisee fit. The constructs extrapolated from this proprietary data limited our use of more robust statistical techniques such as structural equation modeling because the reliabilities were relatively low. However, we took several measures to address this shortcoming. First, within the original construct’s confines, we sought out factors that provided the most solid reliability using traditional exploratory factor analysis techniques. Second, as these were proprietary constructs, we identified more widely recognized scales for comparison. In doing so, we demonstrated that the items used to measure our constructs provided considerable face validity in terms of makeup and reliability to those in the extant literature. Future research should take a more rigorous approach to validate our results using more established scales in similar contexts. Our analysis of a single franchise system is another limitation and weakens the overall generalizability of the study’s findings. Specific idiosyncrasies inherent to this particular franchisor and the fitness industry, in general, may not apply to other franchise systems or industries. However, focusing on a single organization minimizes inter-firm and inter-industry nuances and provides a solid baseline for future research.

We encourage additional research to build on our study’s results as personal initiative and self-awareness are not the only promising psychological characteristics that may influence how a franchisee’s preference for independence may impact financial performance. For example, future researchers could examine how franchisee leadership attributes impact the autonomy-performance relationship. While franchise organizations may risk suffering deficits in financial performance due to a desire for autonomy, it may be that the leadership ability of the franchisee mitigates those effects, providing more tools for franchisors in either the construction of a franchise business or the training of potential franchisees.