1. Introduction

Given the advent of online shopping and social commerce, social media has been a critical modern tool in enhancing buyer-seller interactions (Agnihotri et al., 2016) and sales professionals (Niedermeier et al., 2016). Davison et al. (2018) argued that social media appears to be the modern gateway to the ancient and culturally unique guanxi networks rooted in the Confucian culture context. The Chinese term guanxi generally describes a particular type of relationship or social connection bonding the exchange partners through the reciprocal exchange of favors and mutual obligations and deeply dominating every realm of life in Confucian-rooted society (Y.-Y. Yang, 2000). Recently, the effectiveness of buyer-seller guanxi in social commerce has emerged as a critical research topic (Busalim et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2018). The role of buyer-seller guanxi in social commerce and its facets (i.e., ganqing, renqing, and xinren or mianzi) are also confirmed to be positively related to eWOM sharing intention and social shopping intention (Shao & Pan, 2019; X. Yang, 2019).

However, the existing research could overlook the mediating role of buyer-seller guanxi positioning between guanxi facets and their impact in social commerce, based on the buyer cognition of buyer-seller guanxi position (e.g., zi-ji-ren, shou-ren, or sheng-ren) (Y.-Y. Yang, 2000). According to the theories developed by Y.-Y. Yang (2000) and Wong & Chan (1999), the significant guanxi facets—ganqing and renqing play essential roles in conducting an individual’s perception of guanxi positions toward the counterparty, and the specific perception reflects the psychic distance and interaction rules between Chinese counterparts (Fei et al., 1992; Hwang, 1987). Thus, the guanxi facets tend to be the antecedents of a specific guanxi position. The sharing and purchasing intention should result from the consequent interaction rule due to the particular guanxi position. The guanxi positioning can fill the gap in explaining how each of the guanxi facets facilitates a buyer’s social commerce intention (i.e., sharing intention and purchasing intention) by providing a complete explanation. In short, guanxi positioning refers to people’s way of treating their counterparties in a guanxi network rooted in the Chinese culture. The guanxi positions toward the counterparty lead to rules of interaction between parties. We expect that the buyer’s perception of guanxi position toward a seller results from the buyer-seller guanxi facets and reveals the way of treating the seller, which determines a buyer’s social commerce intention. Rare research incorporates the role of guanxi positioning from the buyer’s perspective on social commerce with empirical evidence.

In addition, recently, the swift guanxi, an extension of traditional guanxi, has been adopted and confirmed to drive consumer repurchase intentions and behaviors due to its swift nature (Ou et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the concept of swift guanxi still cannot capture the whole guanxi features in social commerce since the buyer-seller guanxi is not necessarily so “swift.” It could be built on ascribed or prior guanxi bases (e.g., schoolmates, colleagues, and acquaintances). Thus, the swift guanxi concept may not explain the complete mechanism behind buyer-seller interactions in social commerce. This research argues that a buyer’s identity of the buyer-seller guanxi position in social commerce, no matter the buyer-seller guanxi is rooted in traditional guanxi or swift guanxi, is determined by these critical guanxi facets and expected to determine the level of a buyer’s sharing and purchasing intention in social commerce. To the best of our knowledge, it might be the first time the concepts of guanxi positioning are applied in social commerce and explaining how these guanxi ideologies and related interaction rules lead to the social commerce intention.

2. Theoretical background

2.1 Guanxi concept and its facets

For thousands of years, guanxi is usually considered Confucian culture and acknowledged as the rule people follow in Chinese society. Guanxi can be regarded as “special personal relationships” (K.-S. Yang, 1995) or “particularistic ties” (Hwang, 1987). Guanxi is also based on prior personal relationship bases (e.g., family members, classmates, or colleagues) and developed through continuous reciprocal exchanges of favor (Y.-Y. Yang, 2000). Being different from Western social exchange conventions, e.g., calculative commitment, mutual equity in the relationship, and a contract-based legal system (Wee, 1994), guanxi plays a dominating role in ruling people’s behaviors in Confucian society (Chung, 2019).

Over the past years, many dimensions of guanxi have been proposed. Barnes et al. (2011) divided guanxi into three guanxi facets, namely ganqing (an affective element), renqing (reciprocation and favor), and xinren (trust and credibility). These facets are confirmed to facilitate cooperation and coordination between parties and greater relationship satisfaction. Following the approach of Barnes et al. (2011), X. Yang (2019) confirmed the functional role of guanxi in social commerce. Wang et al. (2014) argued that guanxi could be considered as a relationship-specific investment (RSI), including ganqing (affect investment), renqing (favor exchange), mianzi (face management), xinyong (trust and trustworthiness). L. S. Chen et al. (2017) examined how guanxi facets, i.e., ganqing, renqing, and mianzi, influence social media technology acceptance. Xinren or xinyong are regarded as part of the guanxi facets, but some differences need to be noticed (Tirpitz & Zhu, 2015). Xinren can be considered the Chinese version of trust and a personal belief in someone. Xinyong means the extent to which an individual keeps agreements or promises (Berger et al., 2015). People in Chinese society usually trust (xinren) a person who is trustworthy (xinyong) (Yen et al., 2011). Therefore, we regarded xinren or xinyong as the result of guanxi development rather than one of the guanxi facets. Consistent with L. S. Chen et al. (2017), this study asserts that guanxi facets comprise ganqing, renqing, and mianzi, playing different roles in social commerce.

How an individual’s perception of guanxi position toward the counterpart is formulated and further determines the interaction rules between parties (Hwang, 1987) is another focus of guanxi related literature, suggesting Chinese people tend to treat their counterparties according to the identity of their counterparties rather than the power bases the counterparty has. For example, suppose one is regarded as his counterparty as a zi-ji-ren (those on their side). In that case, the obligation rule is adopted, and his counterparty’s unconditional help is also expected (Fu et al., 2006). By contrast, if one is perceived as a sheng-ren or wai-ren (strangers), the instrumental rules are adopted owing to the lack of ascribed or prior guanxi bases and trustworthiness. Similarly, Li et al. (2018) also contended that friendship quality determined by social tie does matter in social commerce, and the identity of “good friends” toward sellers (friends with a solid social tie) helps buy more high-price- or high-risk-products. However, the identity of “simple friends” (friends with a weak social tie) is not as attractive as “reputable strangers” having good user reviews (i.e., reputable strangers).

2.2 How buyer-seller guanxi facets lead to guanxi positioning in social commerce

As previously mentioned, the guanxi position reflects one’s perceived psychological distance between counterparties and leads to different interaction rules toward the counterparty in a guanxi network (Fei et al., 1992). Many researchers proposed many typologies of guanxi positions. K.-S. Yang (1995) proposed three types of guanxi positions, namely jia-ren (relationships with family members), shou-ren (relationship with acquaintances), and sheng-ren (relationships with strangers), in terms of relationship closeness and ascribed (prior) relationship base (X.-P. Chen & Chen, 2004; Sternquist & Chen, 2006; Tsui & Farh, 1997). Using the level of ganqing and renqing, Y.-Y. Yang (2000) provided four types of guanxi positions, i.e., zi-ji-ren (family member or iron friend, high ganqing and high renqing), ascribed zi-ji-ren (affinities or distant relatives, low ganqing and high renqing), affective zi-ji-ren (close friends or mates, high ganqing and low renqing), and wai-ren (strangers, low ganqing and low renqing). However, Wong & Chan (1999) used the adaptation and ascribed/prior guanxi bases (insider/outsider) to define the guanxi position. According to the arguments of Wong & Chan (1999), the adaptation can be considered as a proxy to represent the level of ganqing between parties, and the ascribed/prior guanxi bases also reflect the extent to which the renqing concern toward the counterparty (Y.-Y. Yang, 2000; Yen et al., 2011). To sum up, most researchers utilized the significant guanxi facets, i.e., ganqing and renqing perception, to classify an individual’s guanxi position toward the counterparty. The buyer perception of buyer-seller guanxi position can be constituted by the ganqing and renqing perception between buyer and seller, further determining the interaction rules toward the seller in social commerce.

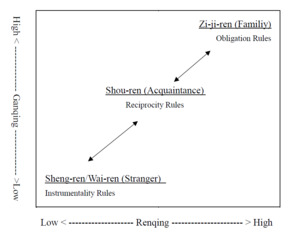

As shown in Figure 1, Y-axis reveals the level of ganqing, and X-axis represents the level of renqing. Zi-ji-ren indicates a high level of renqing and ganqing. The obligation rules will be adopted in this zi-ji-ren guanxi position, and individuals in zi-ji-ren group can count on each other due to their unconditional supports and entire trustworthiness (xinyong). Sheng-ren (stranger) features a low level of renqing and ganqing. Individuals in sheng-ren group adopt the instrumental rules to treat each other since their low level of trustworthiness or xinyong. People in shou-ren (acquaintance) group follow the reciprocity rule due to the middle level of renqing and ganqing between parties. Noticeably, the interpersonal guanxi position is dynamic because of the possible changes of ganqing and renqing between parties (X.-P. Chen & Chen, 2004). A sheng-ren will become a member of shou-ren group or zi-ji-ren group when both parties find themselves connected by an intermediate or prior guanxi connection or through cultivating ganqing resulting from continuous interaction (Y.-Y. Yang, 2000). On the other hand, the zi-ji-ren guanxi position also possibly degenerates into the shou-ren or sheng-ren position due to the decreasing ganqing resulting from the low level of interaction or declining renqing concerns caused by losing prior common connections.

According to the guanxi-related literature, guanxi positioning also reflects one’s need for mianzi preservation for his counterparty and the expectation of the counterparty’s roleplaying in a guanxi network. For example, to a seller, the nearer to the zi-ji-ren guanxi position (insider), the more likely the obligation rule is adopted. Then, a higher level of mianzi preservation is expected since causing the seller to lose face violates the norms of obligation and consequently causes a risk of losing close guanxi between parties. Besides, the zi-ji-ren position, which is featured by the high ganqing and high renqing, may also enhance the buyer’s willingness to give the seller mianzi to show empathy, feeling, or emotional attachment. Therefore, the buyer-seller guanxi position reflects the psychological distance, interaction rule, and need to give or save the counterparty’s mianzi.

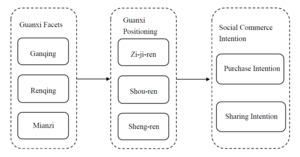

We argue that guanxi facets constitute the buyer-seller guanxi position. The specific guanxi position reflecting the psychological distance and the buyer’s interaction rule with the seller further determines the buyer’s sharing and purchasing intention in social commerce. Figure 2 demonstrates the antecedents and consequences of the buyer-seller guanxi positioning.

3. Research Method

This study investigates the antecedents and consequences of the buyer-seller guanxi positioning in social commerce. To do this, we first conducted a validity and reliability analysis of the scales used to measure those variables, including buyer-seller guanxi facets and buyer’s social commerce intention. Following this, a cluster analysis was conducted based on three buyer-seller guanxi facets. The multiple analysis of variance and Duncan multiple range tests were used to check for differences across clusters on those two dependent variables, i.e., sharing intention and purchasing intention. Finally, according to the results, we provided more insights into the nature of the clusters.

3.1 Measurement

Considering the participants’ getting involved in social shopping online, we adopted a questionnaire-based online survey for gathering relevant data. At the beginning of the questionnaire, we first asked participants to evaluate the guanxi facets with their counterparties (sellers) according to their most recent experience in social commerce. After the participant indicated their perception of buyer-seller guanxi facets, the participant was then asked to evaluate their social commerce intention in the future.

To measure the buyer-seller guanxi facets, we adopted a behavior-oriented approach focusing on the guanxi-related activities, i.e., ganqing-, renqing-, and mianzi-related activities between parties. We developed multi-item seven-point scales (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree) to measure the extent to which each of these guanxi-related activities is performed well (Barnes et al., 2011; Berger et al., 2015; L. S. Chen et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2014). As regards the measurement of the buyer’s social commerce intention, we developed multi-item seven-point scales (1=extremely small extent, 7=extremely large extent) to measure the extent to which the possibility of the participant’s sharing and purchasing intention for the next time, adopting from (AI-Adwan & Kokash, 2019; Li et al., 2018; McFarland et al., 2006).

We first refined the meaning of each questionnaire item according to four experts to ensure content validity and reduce item ambiguity. We also utilized different scale formats and anchors (e.g., “strongly disagree–strongly agree” and “extremely small extent–extremely large extent”) to help prevent evaluation apprehension. Considering the potential social desirability, we also informed all participants that their anonymity would be protected. To avoid the misunderstanding of wording and validate the correction of translation, we back-translated the questionnaire between English and Chinese versions to double-check if the meanings of each item are consistent. Table 5 lists our measurement items.

3.2 Sample and data collection

We chose university students who studied in several universities in Taichung, Taiwan, as our target participants since these people aged 18 to 24 were the largest social media user group (TWNIC, 2020). In the beginning, we sent the hyperlink of the online questionnaire survey through the social media chart room to 54 senior university students of six representative universities who voluntarily participated in this study. Using the snowballing sampling (L. S. Chen et al., 2017), we encouraged the participants to share the hyperlink message forward to their friends on social media until that number of participants at least reached 50 within each university. During the survey period, we collected 381 samples, and only 333 responses were usable. The basic description of the sample is shown in Table 1. Early and late responses were also compared on all latent constructs using traditional t-tests following the recommendation of Armstrong & Overton (1977), and the results indicated that nonresponse biases did not appear to be a significant problem.

4. Results and discussion

4.1 Confirmatory factor analysis of buyer-seller guanxi facets and buyer’s social commerce intention

We employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the validity and reliability of all constructs, including buyer-seller, guanxi facets (i.e., ganqing, renqing, and mianzi), and buyer’s social commerce intention. After dropping some items due to their multi-collinearity (i.e., GAN2 and MZI3 in Table 2), the final CFA model shows a close fit (Chi-square = 50.17, df = 39, Chi-square/df = 1.286, P-value = 0.108, GFI = 0.977, AGFI = 0.947, RMSEA = 0.029). Table 2 shows the standardized regression weights, means, and standard deviations of all scale items, including those that are deleted. According to the skewness and kurtosis coefficients and Q-Q plots of all scale items, the probability distribution of all observations appears to be normally distributed. The Bollen-Stine bootstrap procedure also was employed to test the adequacy of the hypothesized model (Bollen & Stine, 1993). Based on 2000 bootstrap samples, the Bollen-Stein bootstrap p-value is 0.550 (>0.05), indicating that the hypothesized model is acceptable.

Table 3 reveals all constructs’ correlation matrix and average variance explained (AVE). All composite reliability coefficients attained the acceptable 0.7 level. The AVE for all constructs was greater than 0.5, supporting the convergent validity of the measurement items. The square root of AVE for each construct was higher than its correlation with all other constructs, supporting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Given that few correlations in Table 3 are above 0.70, a multicollinearity test was conducted. Results indicated that the highest VIF was 4.39, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a serious concern.

4.2 How buyer-seller guanxi positioning determines the buyer’s social commerce intention

Using the factor scores of the 13 items from CFA, a two-stepped cluster analysis was conducted to examine whether buyer-seller guanxi facets can identify the potential buyer’s perception of the buyer-seller guanxi position. First, hierarchical clustering utilizing Ward’s method was employed to determine the appropriate number of clusters. Three to four solutions were considered based on prior research on guanxi position typology. According to the dendrogram, the cubic cluster criterion plot, and the Pseudo-F statistic, a four-cluster solution is the most interpretable and meaningful (Johnson, 1998). Second, the cluster centers were used as the seed points in k-means nonhierarchical clustering (Hair et al., 2014). Four clusters were ultimately obtained, with 111, 101, 70, and 51 consumers.

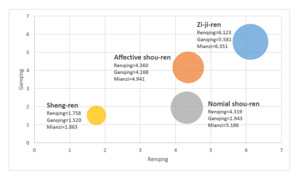

To verify the membership of the four clusters and assess the stability of the clusters, we performed a discriminant analysis. The results indicate that the percentage of cases correctly classified was 96.99%. We named each cluster according to the mean score pattern of guanxi facets (see Table 4). For instance, Cluster 1 can be regarded as “zi-ji-ren” due to its highest scores on all predictor variables. Both Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 can be considered “shou-ren” due to their middle levels of renqing and mianzi among the four clusters. However, owing to the higher level of ganqing in Cluster 2 than in Cluster 3, we named Cluster 2 as “Affective shou-ren” and Cluster 3 as “Sensible shou-ren.” We named Cluster 4 “Sheng-ren” (stranger) due to the lowest scores on all guanxi facets. The cluster analysis results indicate that each buyer-seller guanxi facet can predict the buyer-seller guanxi position. The zi-ji-ren cluster reveals the highest level of sharing intention and purchasing intention.

4.3 Comparing the buyer-seller guanxi positions

Once the clusters were identified and named, we tested whether the buyer-seller guanxi positions, which were determined by buyer-seller guanxi facets, differed significantly from any of the buyer’s social commerce intentions. As shown in Table 4. the ANOVA for buyer’s sharing intention (F-value = 213.230, p < 0.001) and purchasing intention (F-value = 151.986, p < 0.001) are all significant at p < 0.001. Duncan’s multiple range test further justified the categorization. Zi-ji-ren position and sheng-ren position were significantly different from each other in terms of the level of ganqing, renqing, and mianzi. Affective shou-ren and nominal shou-ren were significantly different from the other positions for renqing, mianzi. Sellers in the zi-ji-ren position were perceived as having the highest level of each guanxi facet by buyers, but sellers in the sheng-ren positions were the opposite.

As we expected, the buyer’s perception of buyer-seller guanxi position exerts more meticulous predictions on the buyer’s social commerce intention since each cluster reflects various combinations of buyer perception of guanxi facets. The results also reveal that the nearer to the zi-ji-ren position the buyer considers the seller, the higher the level of each guanxi facet perception and the buyer’s social commerce intention (see Figure 3). Thus, how a buyer considers a seller reflects the buyer’s perception of buyer-seller guanxi facets and determines a buyer’s sharing intention and purchasing intention in social commerce. In addition, the level of buyer’s sharing intention results from different buyer-seller guanxi positions, indicating how a buyer considers the seller and such an identity—zi-ji-ren, shou-ren, or sheng-ren do matter in facilitating the buyer’s social commerce intention (see Figure 4). In Figure 3 and Figure 4, the circle size represents the level of mianzi in the guanxi position.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to investigate the antecedents and consequences of a buyer’s guanxi positioning with a seller in social commerce. This study contributes to buyer-seller relationship management and personal selling in social commerce. Several theoretical and practical contributions can be derived from the results.

5.1 Theoretical implications

This study complements the current guanxi literature by examining how the individual guanxi facet determines the implicit ideology–the buyer’s guanxi positioning toward a seller in social commerce, and how the buyer-seller guanxi position leads to a buyer’s social commerce intention. First, the results bridge the gap of the role of traditional guanxi and related ideologies in social commerce in the context of Chinese society. The results confirm that the traditional buyer-seller guanxi facets can be used to classify a buyer’s guanxi position with a seller in social commerce. According to guanxi-related literature, such a guanxi position reflects a buyer’s identity of a seller and further determines how a buyer reacts to a seller’s offerings in social commerce. Our results also provide empirical evidence of buyer-seller guanxi positions and confirm their antecedents in social commerce. Our results prove that the traditional guanxi facets still matter in social commerce and form a buyer’s holistic guanxi position with a seller. Prior research confirmed the individual effect of each guanxi facet on social media and social commerce. However, we fix the missing linkage between these guanxi facets and buyers’ social commerce intention by investigating the mechanism of buyer-seller guanxi position, which reveals the psychological distance between parties and justifies the buyer’s implicit discrimination between zi-ji-ren (insider) and sheng-ren (wai-ren/outsider).

In addition, our research expands existing knowledge of buyers’ typologies of the buyer-seller relationship. Li et al. (2018) adopted the Chinese guanxi perspective and investigated the effects of buyer’s perceived buyer-seller friendship and its relationship quality on purchase intention. Instead of using the buyer’s perceived friendship with a seller, this research adopted the perspectives of Y.-Y. Yang (2000) and Wong & Chan (1999) and demonstrated how guanxi facets form a buyer’s guanxi position with a seller, and that position further determines the buyer’s social commerce intention. Our results demonstrated that the buyer-seller friendship and its relationship quality reveal partial features of a buyer’s guanxi position with a seller in social commerce. Moreover, our results imply that the buyer-seller guanxi facets and guanxi position are the two sides of one thing, and their consequences determine social commerce intention. Our findings also explain why the buyer’s identity of the seller matters more than the evaluation of the product or service the buyer needs in social commerce in the context of Confucian-rooted society. To the best of our knowledge, little research has been done in social commerce.

5.2 Practical implications

Doing business through social commerce has been the first option for people who want to start an online business. Our study confirms that Taiwanese do extend their traditional guanxi ideology to social commerce as we expected. Personal sellers on social media can derive several implications from this study’s findings. First, the critical role of buyer-seller guanxi positioning in social commerce should be noticed. For those running their selling business in social commerce, the typology provides important guidance on understanding and assessing the factors (i.e., guanxi facets) that lead to various buyers’ guanxi positions with the seller. Thus, transforming the buyer’s existing guanxi position with the seller into the shou-ren position or even into the zi-ji-ren position is likely to increase the buyer’s social commerce intention effectively. Due to the depth influence of Confucian culture, people in Taiwan always love to help the insiders (i.e., zi-ji-ren and shou-ren) in their online or offline social network, following the reciprocity and obligation rules. Taiwanese prefer dealing with zi-ji-ren or shou-ren in their guanxi network and avoid dealing with sheng-ren or wai-ren (stranger) (Leung et al., 2011; Yen et al., 2011). Our results suggest that nurturing the online and offline buyer-seller guanxi facets should be a good start to transform the existing guanxi position into zi-ji-ren since the nearer the zi-ji-ren position, the higher level of buyer’s social commerce intention.

Second, the typology provides sellers important insights on how buyers’ social commerce intention is determined by guanxi positioning. Thus, letting a buyer feel he/she is treated like a zi-ji-ren or shou-ren could transform his/her identity of the seller and willingness to get more involved in social commerce. Understanding and assessing buyers’ needs online and providing more targeted service offerings will differentiate the target buyer and let the buyer feel like being treated as a family in a guanxi network. For instance, doing renqing (favor), giving/saving mianzi, or keeping ongoing online and offline social interactions to convince the target buyer being treating a zi-ji-ren will be rewarded by the buyer’s high level of social commerce intention. However, the buyer’s social commerce intention needs the long-term nurturing and dedicating of buyer-seller guanxi facets; otherwise, the buyer-seller friendship and relationship can be “swift,” and the buyer’s social commerce intention can be damaged.

5.3 Limitations and future research directions

A few limitations should be acknowledged. All measures and results in the questionnaire were self-reported. Future research could be broadened to compare the dyadic perspective to explore if different cognitions exist between buyer and seller. More research variables should also be incorporated, such as widely divergent buyer and seller personal characteristics, and so on. Especially the different perceptions due to different generations also merit more investigations.

Acknowledgment

This research is partially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, R.O.C. under Grant no. MOST 109-2410-H-324 -004 -.