1. Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) is a complex construct that has been defined and instrumentalized to measure in various ways in recent decades (Bar-On, 2006; Brackett et al., 2012; Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2006; Mikolajczak et al., 2015). Over the time, it shifted from being a questionable concept to become an element of special interest to understand individual differences, to develop interaction and communication skills with others, to access job opportunities, to improve school performance, among others.

Notwithstanding some polisemy on the concept, it is fairly agreed that EI is a multidimensional construct referred to the ability to understand, manage the emotions of one’s own and those of others, as well as the possibility of regulating and modifying them (Bar-On, 2006; Salovey et al., 1995). The growing interest in emotional intelligence connects with rapid social and organizational moves, which follows the evolution of individuals’ interests (Dulewicz & Higgs, 1998).

As a result, we find a rapid change of work processes deeply influenced by the adoption of new technologies which, by its turn, change demands of the market, characterizing this new time of globalization and knowledge (Pôrto et al., 2020). The beginnings of the theoretical formulation for the concept of EI were proposed by Salovey & Mayer (1990), who defined EI as “the ability to direct one’s own feelings emotions and that of others; know how to discriminate between them, and use this information to guide thought and self-action” (pp. 189). Later on, Salovey et al. (1995) provided a theoretical framework form EI as well as an empirical instrument for self-reporting the so-called called “Scale trait of metacognition of emotional states” (Trait Meta-Mood Scale, TMMS-48) which yields three dimensions on on EI (clarity, attention and emotional repair) and allows evaluations on perceived emotional intelligence (PEI).

Subsequently, a Spanish version of the empirical instrument, the TMMS-24 was adapted by Fernández-Berrocal et al. (2004), who halved the number of items in the instrument, although retaining its conceptual structure and dimensions of the original. Thus, the instrument has been used in different research contexts, both in the field of social psychology (Aguilar-Luzón et al., 2012; Garrido et al., 2011) and health sciences (Aradilla-Herrero et al., 2014; Lara et al., 2014; Lizeretti et al., 2012) among others. In recent work, Vaquero-Diego et al. (2020) used the TMMS-24 instrument, translating it to Portuguese and applying that to a large scale survey in Brazil, which rose questions on the cross-cultural validity of the instrument and prompted the analysis we will be reporting in this paper. Also, EI studies have been affecting the mainstream thinking on areas of personal development (Rey Peña et al., 2011). On the one hand, it has been found that high levels of EI are positively related to optimism (Extremera et al., 2007), health (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2006), self-esteem (Schutte et al., 2002) and adaptation (Boyatzis & Saatcioglu, 2008). On the other hand, low levels of EI are related to alcohol and drug use, and a high rate of conflicting behaviors (Mayer et al., 2008) and the burnout syndrome (Blanch Plana et al., 2002).

From the educational research sphere, emotional intelligence is gaining particular interest as it envisions benefits in bringing it not only to students but to all the members of school community (Botey et al., 2020). Within the training of students, EI has been shown positively correlated to academic performance, once it influences stress management, intrapersonal skills development and adaptability (Parker et al., 2004). Also, it helps to adjust and clarify thoughts (both negative and positive), promoting an emotional regulation and subsequently, influencing academic performance (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2001). Furthermore, Aguayo-Muela & Aguilar-Luzón (2017) showed that an “emotional educator”, i.e. a teacher who has balanced his own emotions, can help students to learn and to develop emotional and affective skills, which is related to the intelligent use of their emotions.

In this regard, instruction on emotional skills could promote personal and intrapersonal skills for students, complementing, thus, their academic training with qualities beyond traditional contents, that contribute to shaping their leadership and, ultimately, could give greater opportunities for succeeding in their later professional careers in a world with an increasingly competitive labor market (Hourani et al., 2020). Some authors, in particular, argue that research supports the conception that EI is a predictor variable for a person’s performance in the workplace (Boyatzis & Saatcioglu, 2008), which in turn can be useful in selection processes (Izquierdo et al., 2007). Their assumption is that people with a high level of EI are more adaptable to stressful life events, using more appropriate coping strategies, coupling the capacity for teamwork and, therefore, would be more likely to successful in the professional field (Bar-On, 1997; Gonzalez et al., 2017; Nikalaou & Tsaousis, 2002; Prati et al., 2003).

Thus, this work aims to cross-culturally empirically validate a psychometric instrument, largely used in Europe, in a large sample of adolescents in Brazil, comparing latent dimensions an items relational structure, in order to amplify its uses for newer cultural sets.

2. Theoretical framework

Brazilian education within the Latin American context requires research that accompanies the evolution of civilizations in new contexts, and also in this moment of global change. To be able to inform about the mental health and well-being of adolescents, it is necessary to seek information on the functioning of the Brazilian educational system, in this specific case the Sesi Schools Network, in the city of São Paulo, where the research has been carried out, the purpose was to validate a scale of self-perceived Emotional Intelligence in adolescents.

In this sense, this research provides information that can help solve situations that unbalance the well-being of students in this case through education (Formichella & London, 2013; Stallivieri, 2007). With the vision in the education in emotional competences, and for this it is necessary to know the self-perception of Emotional Intelligence that self-inform the students.

Since the 1st World Conference on Health Promotion, held in 1986 in the city of Ottawa (World Health Organization, 1986) educational processes begin to make a place within the field of health, giving it that priority approach to promote personal and social well-being.

WHO reports that mental health is an integral and essential component of health considered as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own attitudes can cope with the normal pressures of his or her life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.”, in order to obtain detailed information, we used the applied scale that collects information to recognize the emotional competencies of adolescents.

Based on this idea, the Education 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goal No. 4 in Education, maintains as a principle the focus on the quality of education in an integral sense, taking into account the emotional competences and well-being of adolescents. Latin American students participate in this international evaluation whose objective is to evaluate in Latin America and the Caribbean the quality of education in basic education (Unesco, 2013).

Authors such as Extremera and Fernández Berrocal (2015) affirm that the main benefits of EI’s work in educational contexts are: improved academic performance, increased well-being and psychological adjustment, increased interpersonal relationships, reduced aggressive behaviors, prevention of substance use and/or other addictive behaviors. Other authors highlight that these emotional benefits are accompanied by cognitive benefits (Durlak et al., 2011).

In this scenario, the Brazilian government, as an educational proposal, chooses to use training units on EI that can be aligned with the objective of maintaining the mental health of the members of the educational community. In this way, it seeks to sustain well-being using some principles of emotional intelligence (Federacion de industrias de Sao Paulo, 2021).

3. Method

3.1. The TMMS-24 instrument

The empirical instrument we are exploring in the present analysis has been widely used to evaluate EI in the realm of human resources. As corroborated by a meta-analysis work, carried out by Martins et al. (2010) and confirmed by Fernández-Berrocal et al. (2012), self-report tests in EI have been used during the last years, and 67% of them corresponded to the TMMS instrument. It have also been used both in organizational (Argoti et al., 2015; Rincón & Rodríguez, 2018) and educational contexts (Colorado et al., 2012; Contreras et al., 2010).

Besides standard demographic info, the TMMS-24 instrument is set of likert type statements (Likert, 1931) consisting of 24 items, divided into 3 key dimensions (8 items each) of emotional intelligence: 1. perception; 2. understanding; and 3. regulation, referred to original ones (clarity, attention and repair). As decribed by Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal (2005), emotional perception (1stdim) is the ability to identify and recognize both one’s own feelings and those of others, while emotional understanding (2nd dim.) implies the ability to deploy a repertoire of emotional signals, label emotions and recognize in which categories feelings are grouped and lastly, emotional regulation (3rd dim.) includes the ability to be open to feelings, both positive and negative, and reflect on them to take advantage of them in a positive way.

3.2. Research context

The study was established on a private school network in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, encompassing students from secondary school (SESI-SP) in the 7th and 9th years of elementary education, and the 3rd year of secondary education, adolescents between 14 and 19. The criterion used for including these courses followed two facts: first, those school years correspond to intense adolescence stages, as described by Aberastury (1983) and Blos (1986); then, by that time (October-December 2017) those classes were taking the São Paulo State Performance Assessment test, which gathered a large number of students at the same time in similar scenario at their school unities.

The TMMS-24 questionnaire was given to 14,000 students, from which we obtain 11,370 responses with 11,283 complete cases (5,699 girls and 5,584 boys), therefore, it is an exhaustive sample of adolescent students from São Paulo. According to the ethical criteria provided by Brazilian law, the study was framed in human research with minimal risks in such a way that all participants were included prior diligence of informed consent, guaranteeing in all cases, the right to confidentiality and anonymity. This study also complies with the ethical considerations of the Helsinki Declaration and the ethics criteria and had previous authorization both from the school network principal and from the parents of the test subjects.

3.3. Procedure

Prior to carry out the survey with the subjects, the Spanish version of the TMMS-24 questionnaire was translated and had its content validity reviewed by members of a research group composed by specialists in educational field, who verified item’s translation, its suitability for the research, retaining the original ideas.

The TMMS-24 instrument was then applied to a pilot group, within the same research group, highlighting the precise definition of the domain and the judgment on the degree of sufficiency with which the domain is evaluated, both relevant aspects of the questionnaire (Barajas & Edith, 2011).

Next, after receiving authorization from the school network, which included a meeting with the principal, a, IT professional received from the researcher an online form, which was spread to the IT teachers in the network. The IT teachers were informed of the objectives of the study as well as instructions for students to answer the TMMS-24 questionnaire. The forms were applied at the computer classrooms, where each student could have his own PC for answer. At all times from the coordination of research, contact was made by phone to IT teachers who apply the questionnaires in the classroom. The instructions detail that filling out the questionnaire involved tacit consent for participation in the study. The time required to complete the questionnaires took between 15 and 25 minutes. Subjects collaboration was voluntary, anonymous and selfless.

3.4. Data analysis

The instrument figures a quantitative instrumental approach and is geared towards addressing the psychometric properties of tests, according to its original constructs. Then, the “likert” data collected was analyzed through (a) descriptive statistics, (b) measurement of internal consistence (Cronbach, 1970; McDonald, 1999) and (c) both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (Fernández, 1998; Martínez Arias, 1995). The data analyses were carried out R Software (Ihaka et al., 1993) software, with the packages cocron (Diedenhofen, 2016), corrplot (Wei & Simko, 2017), HH (Heiberger & Holland, 2020), lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), nFactors (Raiche & Magis, 2020), psych (Revelle, 2020) and semPlot (Epskamp, 2019).

Empirical studies in psychology commonly report that Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of the reliability of internal consistency. However, concerns on Cronbach alpha regarding the problem stemmed from unrealistic assumptions can be seen in methodological studies (Dunn et al., 2014; Geldhof et al., 2014; Peters et al., 2015). Although there are numerous indicators alternative to Cronbach’s alpha, in this study we used also the McDonald’s omega coefficient (McDonald, 1999; Raykov, 2001; Raykov & Shrout, 2002) considering its suitability for discrete variables. Another relevant discussion is the cut-off points definition for internal consistency indexes. In the case of McDonald’s omega, it can be acceptable in ranges varying from .7 and .9 (Campo-Arias & Oviedo, 2008), even though in some circumstances values greater than .65 may be accepted (Katz, 2006). In the case of the Cronbach’s alpha, the minimum acceptable value can be above .6 (Taber, 2018). Avoiding disputes over arbitrary cutting points, both α and ω are reported.

As this study is quantitative in nature, we proceed both descriptive and inferential analysis for comparing emergent dimensions from the TMMS-24 instrument in Brazil to the dimensions reported in the original TMSS-24 Spanish study, in order to validate its usage in the South American context. Fernández (1998) stresses that it is understood that an instrument is reliable if it has consistency with respect to its application in various environments (different places and/or time). On the other side of the coin, validity can be considered as an attribute indicating the degree to which the instrument measures the constructs for which it has been created. Thus, the numerical indicators computed were used for inferring both reliability and validity of the test in a cross-cultural context.

4. Results

The overall internal consistency indexes computed were αcronb = .90 and ωmcdon = .92.

The Scree test informed that 3 components are enough for explaining most of data variance (Fig. 1, left), showing three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 (λ1 = 6.656, λ2 = 3.482 and λ3 = 2.260), which accounted for 46% of total data variance. The Spearman’s correlation matrix for p < .05 reject only q5/q15 correlation (Fig. 1, right).

The exploratory factor analysis and items respective loads (> .35) in each factor are shown in Table 1, detailing per factor both internal consistency index used and the amount of explained variance.

The structural analysis showed a model a priori containing all items of the TMMS-24 instrument (Fig. 2, upper). A multidimensional projection was detected for the item 13, and the items 5, 23 and 24 showed loads near to the .35 off point, as a consequence, a model with out-of-range goodness-of-fit indices is obtained. Thus, a structural model a posteriori was proceeded, excluding those ones and retaining the remaining 20 items (Fig. 2 lower).

The posteriori model kept its acceptable internal consistency, maintaining Cronbach’s alpha (αcronb = .90) and increasing McDonald’s omega (ωmcdon =.93). In both models, correlation between emotional clarity and emotional repair are the largest and the pair emotional attention and emotional repair are the smallest.

After the elimination of the 4 items, good results were obtained in terms of the fit indices, affirming the goodness of fit of the TMMS-20 model (AGFI= 0.92; GFI = 0.94; CFI= 0.95; RMSR = 0.06; RMR= 0.08; NFI=0.93).

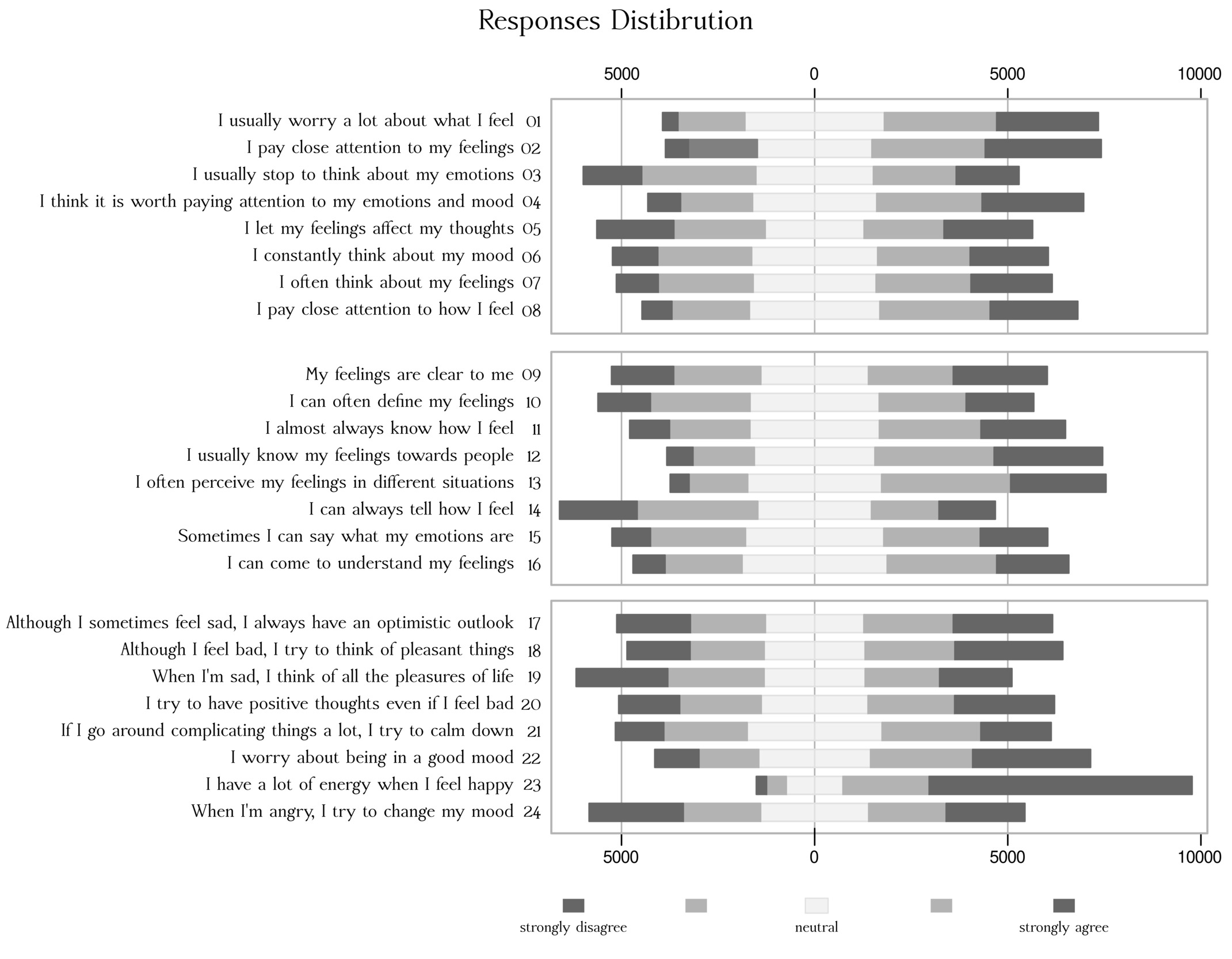

The responses distribution is shown in Fig. 3, explicit the overall tendencies in each item. It can be observed that item 23 is the highest item by far in relation to the others, which could be an element of distortion, as most of them give the same response; strongly agree. Item5 also stands out as the lowest frequency of intermediate values in the attention dimension.

5. Discussion

The dimensions that emerged in the Brazilian adolescent population maintained the same structure as the original research instrument Salovey et al. (1995). That points to the validity of the constructions, even when they are investigated in a different cultural context. This feature reinforces the potential of EI and IPE as a non-idiosyncratic human characteristic. In addition, the high values of the instrument’s internal consistency indices for each subscales support the instrument’s reliability assumption. Likewise, the CFA contributes to validate the constructs, demonstrating that the items tend to cluster in the dimensions of attention, clarity and repair, proposed by the authors of the scale, where items 23 and 24 presented the lowest factorial weight in the repair dimension, 5 and 13 in the attention and clarity dimensions respectively.

Taking into account the elements removed from the original, its divergence from the TMMS-24 may stem from the translation process or from social or cultural differences with respect to self-declaration. The 4 items removed from the instrument were 5, 13, 23 and 24, in general because they did not reach valid values both in the analytical part (model with poor goodness-of-fit indices) and in the conceptual part, since in the regional context they do not show consistency with the definition of the corresponding construct.

In particular, item 5 corresponds to the dimension of attention, which confronts the subjects with the possibility of feeling and allows feelings to flow, this can cause this item to lead to a misunderstanding about a lack of control over feelings. Item 13 corresponds to the dimension of clarity and questions the number of times the interviewee recognizes and understands their emotional states, as it is a quantitative response and does not specify the specific amount in each option on the Likert scale, it can lead to an error in the answer. Item 23 corresponds to the repair dimension and aims to determine the level of performance and management thrills, it may not fit the TMMS model by associating the action of having energy with a feeling of happiness. Item 24 also corresponds to the dimension of repair in the initial scale and its non-inclusion in the Brazilian model may be due to the use and meaning of the verb try (try, in Spanish), since it implies doubts and is difficult to quantify.

There are numerous applications of the TMMS instrument for different contexts in which some items did not reach valid values and were excluded from the instrument, as in the case of Argentina (Calero, 2013), where the researcher submitted the instrument to its validation obtaining a scale of 21 items. In another study, Rincón & Rodríguez (2018) examined the reliability and validity of the TMMS in a group of teachers from private institutions of higher education in Bolivia, also obtaining a reduced scale of 20 Items in their validation. Other studies (Martín-Albo et al., 2010; Salguero et al., 2010) eliminate item 23 from the scale and item 5, because they have low levels of contribution to their dimension. However, Aradilla-Herrero (2014) advises keeping item 23 despite its low contribution.

Once the research is carried out in an educational context, the dimensions detected can offer a path to the curricular trainers in order to include the development of these competences, as suggested by Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal (2006), promoting a broader development for students and preparing them to deal with their own emotional states in a dynamic and often oppressive world.

6. Conclusions

Each culture has its own rules of emotional expression that are acquired through learning and modulate the meaning of emotions. In this way, culture crosses and influences the way in which emotions are interpreted, intensifying, decreasing, substituting or neutralizing their appearance and/or expression (Ekman et al., 1969).

Among the various instruments that exist to measure EI, the Trait Meta-Mood Scale -TMMS- stands out as one of the most widely used tools worldwide. It allows to obtain an index that values the knowledge that each person possesses about their own emotional states, providing a personal estimate on the reflective aspects of the emotional experience.

This study aimed to validate the instrument TMMS-24 (Salovey et al., 1995) in the Brazilian environment, for this purpose it was translated into Portuguese and the texts were adapted to the cultural characteristics of the environment in which it was applied. The internal consistency was adequate and the dimensions that emerged in the Brazilian population studied maintained the same structure as the original research instrument, with the exception that four items were eliminated for reasons stated above. Therefore, with this study is obtained in TMMS-20-BR, which allows the study of the Emotional Intelligence of individuals in the Brazilian population. Having this instrument properly adapted to Brazil allows valid comparisons with the results obtained in other countries.

Among the limitations of the study, it should be noted that the sample used is made up of adolescents from São Paulo and not from the whole of Brazil; perhaps the study could be extended to adolescent populations in other regions.

Learning to face frustration, to control anger, to motivate oneself and to foster empathy are emotional competences whose mastery allows us to be better prepared for life (Pérez Escoda & Filella Guiu, 2019). therefore, educational organizations and school staff must take into account the emotional profiles of students by designing interventions adapted to the recipients with an active and motivating methodology. Therefore, it is essential to have instruments that allow to measure the different aspects of Emotional Intelligence, which facilitates an adequate design of learning and professional trajectories with the aim of obtaining desirable social results such as greater happiness of the person or better performance in the company (Ingram et al., 2019).

Therefore, a very interesting line of research that could be a continuation of this study is to characterize the sample according to sociodemographic variables (age and sex) identifying the possible strengths and deficiencies of each group in EI and designing appropriate learning trajectories that improve their EI.

In recent years, technology has been slowly entering the classroom, but the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the process in an unimaginable way. Thus, in order for educational institutions to know the emotional state and/or capacity of their students, it is necessary to access it possibly through devices that all students possess, with which it is possible to offer to carry out a self-assessment of emotional intelligence on-line. However, in this situation, all interpretation depends on written text and also provides the possibility of more time, allowing the answers to be not so spontaneous. This seems to be one of the future avenues of research, as this change of modality may require an adaptation of the model.

_for_determining_the_number_of_factors_to_retain_and_spearman_s__matrix_fo.jpeg)

_and_our_tmms-20_(below).png)

_for_determining_the_number_of_factors_to_retain_and_spearman_s__matrix_fo.jpeg)

_and_our_tmms-20_(below).png)