Introduction

Economic development is a complex process (Hosseini, 2003), and entrepreneurship remains a crucial pillar to achieve it independently of the different departure conditions a country may have (Galindo-Martín et al., 2021[1]; López-Núñez et al., 2020).

Entrepreneurship development depends heavily on entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Wood & Bandura, 1989), that is related with people’s competencies, translated into a person’s capacity to know, to do, and his/her related attitudes (Jardim, 2010), and this will model entrepreneurship intentions.

Entrepreneurs will always profit from being supported in the development of their entrepreneurial spirit, attitudes, and capabilities. This is what will reinforce the entrepreneur’s self-efficacy, and ultimately will affect a country’s or region’s entrepreneurship potential (Porfírio et al., 2018).

At the same time, considering the dynamics of entrepreneurship among young people (OECD/EU, 2020; Schott et al., 2015), it seems very important to promote entrepreneurship from younger ages, where personality starts to be formed (Peterman & Kennedy, 2003). Analyzing entrepreneurship among secondary school students means looking into their entrepreneurial intentions (Fayolle & Klandt, 2006). The entrepreneurial intention, as defined by Krueger et al. (2000a), consists of the desire to start a business, and thus are the basis of good predictions for development based on Entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial intentions are a result of a state of mind of the entrepreneur, depending on certain entrepreneur’s psychological characteristics, competencies, and skills, being influenced by education (Garrido-Yserte et al., 2020; López-Núñez et al., 2020). By its nature Entrepreneurial Intentions are one of the best predictors of a country’s development trough Entrepreneurship (Krueger et al., 2000b[2]).

The development of entrepreneurial competencies is critical for societal development and to improve progress (López-Núñez et al., 2020). Previous research considers the impact of entrepreneurship education in terms of economic growth, job creation and increased societal resilience, as well as its individual effects in terms of increased school engagement and improved equality (Lackeus, 2015). However, there is a gap in research concerning the concrete youth entrepreneurial activities (Garrido-Yserte et al., 2020).

Several studies analyze university students’ intentions to become entrepreneurs (Bird, 2015; Comisión Europea, 2016; Edelman et al., 2010; Krueger et al., 2000b; Nabi et al., 2017).

It is known that adolescence, where psychological determinants and personality traits of entrepreneurs start to be developed, is a privileged part of life to acquire knowledge (Peterman & Kennedy, 2003). Thus, secondary schools play an important role in activating and developing entrepreneurial skills and develop the societal entrepreneurial spirit of young people. However, there is a lack of research both about young entrepreneurial activities and in terms of the influence of entrepreneurship education in secondary school students. Despite the growing number of entrepreneurship’s school programs developed in European secondary and high schools, authors diverge about the impact of these programs for entrepreneurship development (Garrido-Yserte et al., 2020).

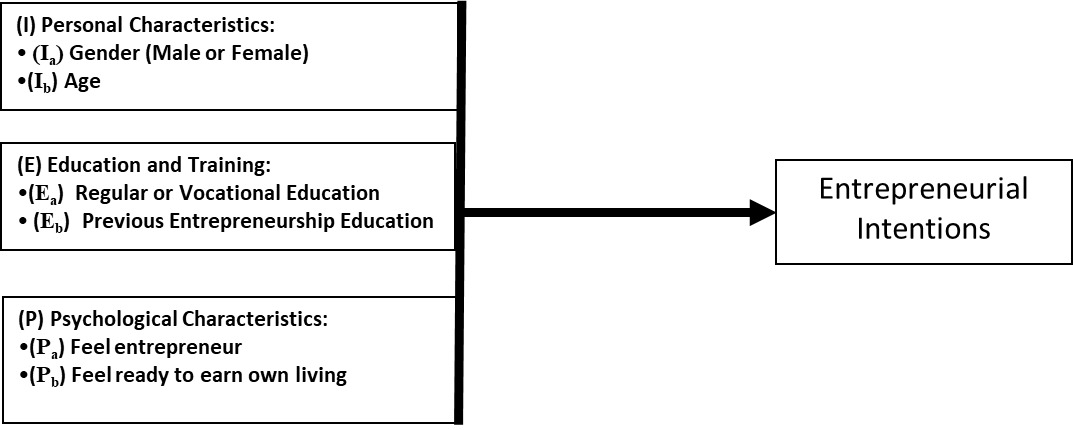

Giving the complexity of entrepreneurship phenomenon, in this research we analyze the impact of entrepreneurship education to promote entrepreneurship intentions in secondary school students, especially considering two important topics: i) possible differences among students from regular courses, when compared to vocational education and associated with the personal characteristics of the potential young entrepreneurs (age and gender); and ii) the use of a balanced program of entrepreneurship education, combining both the development of psychological and management skills among the involved students, adequate to propel entrepreneurial intentions.

At the same time, we argue about the importance of starting the development of entrepreneurship competencies in adolescents (Olugbola, 2017), and not mostly, as it is being done almost everywhere up to now, in university students. We depart from the principle that there are entrepreneurial skills that need to start being developed in the early stages of the personality’s development, that later will be consolidated, and improve entrepreneurship’s potential by reinforcing entrepreneurship’s intentions and ameliorate entrepreneur’s self-efficacy. For this to happen, it is important to consider the different entrepreneurs’ departure conditions in terms of age and gender, as well as education and training, and their psychological characteristics, namely those related with the entrepreneurship venture.

In the following section we develop the literature review, aiming to support the proposed research model in the developed literature. Based on existent knowledge, we pursue with the presentation of our research model and methodology and sample used to develop this research. We present the results, and we draw the conclusions, ending by presenting the research limitations and proposing future research on the topic.

Literature Review

Theory of Planned Behavior and Entrepreneurial self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is a concept derived from organizational research (Bandura, 1997), that is defined as “beliefs in one’s capabilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action needed to meet given situational demands” (Wood & Bandura, 1989: 408). Self-efficacy is one of the actions of perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 2002), being identified with beliefs in individual’s capability to start up and perform the progress of action needed to yield given achievements (Wood & Bandura, 1989).

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991, 2011) states that behavioral achievement depends on both motivation (intention) and ability (behavioral control). At the same time, according to the TPB, the immediate antecedent of behavior is the intention to perform the behavior in question; the stronger the intention, the more likely it is that the behavior will follow (Ajzen, 2020).

The concepts of self-efficacy and TPB are important to analyze the effect on potential entrepreneurs’ behavior and increase their entrepreneurial intentions, namely because Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) is influenced by psychological factors (like self-satisfaction, desire for autonomy, and entrepreneurs’ risk aversion) (Porfírio et al., 2018).

ESE, related to the degree to which a person believes that he/she could take a role and solve duty as an entrepreneur (Mcgee et al., 2009) promotes entrepreneurship development, by increasing entrepreneurship potential (Chen et al., 1998a; Porfírio et al., 2018) through the increase in entrepreneurial intentions (Mcgee et al., 2009).

Education assumes an important role in reinforcing potential entrepreneurs’ beliefs, increasing knowledge about other variables that influence behavior, and may strengthen the entrepreneurs’ attitudes by strengthening their psychological characteristics, namely trust, risk aversion, etc.

Entrepreneurship Education as a driver of entrepreneurial intentions

Entrepreneurship is an intentional process (Loi et al., 2016) whereas entrepreneurial intentions constitute a central issue to promote entrepreneurship development. Education becomes, in this sense, a central topic (Krueger et al., 2000a; Mcgee et al., 2009).

Heuer & Kolvereid (2014) have analyzed the impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Entrepreneurial Intentions having found a strong direct relationship between participation in extensive entrepreneurship education programs and entrepreneurial intentions. These relationships, however, are not so much straight forward (Volery et al., 2013).

Entrepreneurship education programs permit students to develop various aspects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy like modelling, mastery experience, social persuasion, and self-judgment of psychological entrepreneurship- related characteristics (Erikson, 2003; Fayolle et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2005). Systematic and continuous efforts of entrepreneur courses allow the change of student’ perceptions in terms of their entrepreneurial capabilities like risk-taking, innovativeness, beliefs on their capabilities for entrepreneurship (Chen et al., 1998b; Kirkley, 2017) or level of control (Robinson et al., 1991). In a study in ten secondary schools Kirkley (2017) found that the introduction of entrepreneurship education had positive impacts on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes in terms of course relevance, engagement with the teacher, applied learning and perception of a valuable contribution to make to their communities.

However, the effects of entrepreneurship education on academic performance and entrepreneurship intentions are heterogeneous (Athayde, 2009; Atienza-Sahuquillo et al., 2016; Johansen & Schanke, 2014; Pihie & Bagheri, 2010; Volery et al., 2013) and learners’ entrepreneurship attitudes may not change (Steenekamp et al., 2011).

Pihie & Bagheri (2010) found that a systematic training (‘Living Skills’) including enterprise education in lower secondary Malaysian school system, was reflected in higher perception of students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy in terms of awareness about the necessity and importance of entrepreneurship for their community. However, these students showed less skills inherent to opportunity recognition and have a less favorable perception of capabilities to deal with the uncertainty and ambiguity that characterizes the life of an entrepreneur (ibidem).

An entrepreneurship project called ‘Company Program’ (Johansen & Schanke, 2014) concluded that entrepreneurship education improved academic performance in lower secondary schools, but it did not improved this indicator in upper secondary schools. These results reflected different approaches: in lower secondary schools, the project focused on interdisciplinary learning and on stimulating self-confidence, cooperation and creativity; besides, in these schools the way objectives and competence aims in subject were measured is connected with the practice-oriented method of learning of the project; in upper secondary schools the project favored skills and knowledge on how to start and run a firm but the objectives and competence aims in subjects were not well related to this teaching orientation (idem).

In their analyzes of 1748 students’ attitude toward entrepreneurship of sixteen secondary schools, Steenekamp et al. (2011) concluded that the influence of entrepreneurship education did not have any practical effects on leadership, achievement, personal control and creativity. These findings are explained by the fact that entrepreneurial education was largely infrequent and without focus or depth (ibidem).

Volery et al. (2013) found that knowledge developed through entrepreneurship education did not have a significant influence on entrepreneurial intention, and that the development of competencies had even a slightly negative effect on the same variable. It appears that knowledge and entrepreneurial skills favored making a more and better-informed decision against an entrepreneurial career in terms of having more realist perceptions regarding this option (ibidem).

Conversely, in a study of 249 young students (15-19 years old) that set up and run a business during one year in a Company Program, Athayde (2009) concluded that students with self-employed parents showed higher entrepreneurship intentions.

Atienza-Sahuquillo et al. (2016) based upon a sample 49 primary school students (8-12 years old concluded that an increase in entrepreneurship intentions occurred even in a context of a low presence of entrepreneurship family histories.

Personal characteristics: the importance of gender and age to promote entrepreneurial intentions

Some personal characteristics of entrepreneurs remain an important issue to explain entrepreneurial intentions (Park, 2017) and influence entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Several studies state that entrepreneurial behavior can be explained by demographic factors such as gender and age (Liñán et al., 2005; Reynolds, 1997; Shane et al., 1991).

In a study of 216 students from small business programs, Harris & Gibson (2008) analyzed the relationship between gender and entrepreneurial attitude orientation and concluded that, compared to female students, male students scored higher on innovation and personal control. In a similar study focused in 435 Indian Air Force trainees, the results pointed that female students were higher in achievement motivation (Kundu & Rani, 2008). Based upon a sample of 4292 middle and high school students attending entrepreneurship classes, Wilson et al. (2007) findings showed that entrepreneurial self-efficacy of male students was higher compared with female students. Johansen & Schanke (2014) studied the effects of an entrepreneurship education project (‘Company Program’) on gender academic performance of 1880 pupils in lower secondary schools and 1160 students in upper secondary schools. The authors concluded that female academic performance was higher than the male counterparts, although the direct effect of gender on academic performance was stronger in lower secondary schools than upper secondary schools (ibidem). Based upon a sample of 1015 secondary students engaged in entrepreneurial programs, the study of do A. do Paço et al. (2015) showed that boys had substantially higher entrepreneurial intentions than girls.

In the context of entrepreneurial education Kolvereid (1996) concluded that older students showed more human-capital assets, which in turn were reflected in increased entrepreneurial intention. Volery et al. (2013) analyzed the effects of entrepreneurship education on human capital at upper-secondary level, using a sample of 494 pupils attending entrepreneurship programs and 238 students of a control group. Their findings suggest that older students reveal a higher entrepreneurial intention.

Psychological characteristics

In the literature there is a wide consensus that entrepreneurial behavior is influenced by psychological characteristics like autonomy, self-satisfaction, risk aversion, locus of control, or perceptions of the feasibility, benefits, and desirability.

The desire for autonomy (psychological and financial independency) is one of the key-elements that integrate entrepreneurship expectancy frameworks (e.g. Birley & Westhead, 1994; Edelman et al., 2010). Entrepreneurs that express higher needs for autonomy prefer to make decisions alone, care less about other’s rules and opinions and have preference for self-directed work (Cromie, 2000). To set their own goals, to control goal achievement themselves and to develop their own actions, entrepreneurs prefer to make decision with independence relatively to supervisors (Rauch & Frese, 2006).

Regarding self-satisfaction, the choice to be an entrepreneur is favored by the ‘ideal’ firm to work (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011) and higher control on working conditions (Douglas & Shepherd, 2000). As far as risk aversion attitude is concerned, research points out that there is considerable heterogeneity among entrepreneurs (Begley & Tan, 2001; Caliendo et al., 2010). Risk-taking propensity is related with entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Barbosa et al., 2007). In terms of orientation toward entrepreneurship attitude, Robinson et al. (1991) found that, relative to non-entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs revealed higher self-confidence. In a longitudinal study conducted by Brockhaus (1980) entrepreneurial success has a positive correlation with orientation to locus of control. The importance of this orientation is reinforced to differentiate successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs (Brockhaus & Horwitz, 1986).

In primary and secondary schools adopting entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by propensity to take risks (Dinis et al., 2013; Huber et al., 2014; Sánchez, 2013; Volery et al., 2013), need for autonomy and perceptions of feasibility, desirability and benefits (Volery et al., 2013), self-efficacy and proactiveness (Huber et al., 2014; Sánchez, 2013), self-confidence and need for achievement (Dinis et al., 2013; Huber et al., 2014) perceived behavior control (A. M. F. do Paço et al., 2011) and ‘coping with unexpected challenges’ (Pihie & Bagheri, 2010).

Based upon a sample of 74 secondary students, Dinis et al. (2013) found that lower self-confidence and lower propensity to take risks negatively influences entrepreneurial intentions, and that need for achievement positively influences entrepreneurial intentions. In a similar study based upon the same sample, A. M. F. do Paço et al. (2011) concluded that perceived behavior control positively influences entrepreneurial intentions. In the analyses referred above on upper-secondary level, Volery et al. (2013) found that higher propensity to take risks, need for autonomy and beliefs (perceived desirability, feasibility, and benefits) had a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention. In their study of 3000 students from vocational and technical secondary schools, Pihie & Bagheri (2010) concluded that the variable ‘coping with unexpected challenges’ had a significant positive relationship with entrepreneurial intention to develop new products and market opportunities. In a study of 729 secondary students Sánchez (2013) concluded that the higher the risk-taking, the proactiveness and self-efficacy with respect to self-employment, the higher the entrepreneurial intentions. Based upon a sample of 2413 primary school student (11-12 years old) engaged in a entrepreneurship program, Huber et al. (2014) found that increased self-efficacy, need for achievement and risk-taking propensity had a negative effect on entrepreneurial intentions. Students’ future career path may be not directly related to this program since the phase to choose an occupation is still quite remote for them (ibidem).

All these findings are important to model the contents of entrepreneurship education programs, and thus influence the capacity of these programs to model those psychological characteristics in order to improve entrepreneurship intentions.

Methodology

Sample

Our sample has 1.750 secondary school students, from the 10th (42,7%); 11th (31,1%) and 12th (26,2%) year of scholarity. 51,1% of the students involved are female (48,9% male), and 46,1% of the students were from the vocational training system (53,9% from the regular school system). Used sample represents about 0,453% of the overall group of Portuguese secondary regular school system, and about 0,696% of the total vocational students of Portugal. Most vocational education students are older (between 16 and 18 most of them) than the students from the regular school (the majority being between 15 and 17 years old).

Most of the schools have adopted a systemic entrepreneurship educational program, entitled “Originals”. Just about 23,3% of students did not receive this training.

This entrepreneurship education program intended to deliver students some psychological tools to promote entrepreneurial competencies and attitudes allowing them to better face entrepreneurship challenges. Where possible, this program also included the teaching of different management tools to better prepare students to be alert to and to be prepared to manage entrepreneurship opportunities or needs during their lifetime. Most of these students at the different school years were invited and have participated in a final entrepreneurship ideas’ contest at the end of their training.

Research method

This research aims to identify the conditions to develop entrepreneurship intentions among secondary school students in Portugal. We apply a Multinomial Logistic Regression model (MLR) to the intended categorical data analysis. MLR deals with nominal/ordinal dependent variables that can have more than two categories, whether nominal or ordinal variables, and has been widely applied in many different research areas. MLR allows to predict the category membership on a dependent variable based on multiple independent variables, whether they are dichotomous or continuous.

We use real data from a survey conducted to 1.750 students at Portuguese secondary schools. To identify more closely the possible relations between characteristics and their effects on entrepreneurial intentions, we use some cross-tabulations supported by a set of chi-squared statistical tests.

A total of seven conditions were used to characterize our outcome (the entrepreneurship intentions).

To further enhance our results, after checking the variables that influence entrepreneurship intentions, we have decided to run a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) (Fiss, 2011; Kraus et al., 2016; Roig-Tierno et al., 2017; Schneider & Wagemann, 2009; Woodside, 2013), in order to assess the combinations that best suited our goals.

After removing missing values (especially in the questions regarding the entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship intentions), to use fsQCA variables have been calibrated as follows:

- Course: 0 = Regular education; 1 = Vocational Education

- Form: 0 = Did not have participate previously in the entrepreneurship education program; 1 = Have previously participated in a entrepreneurship education program

- Gender: 0 = Male; 1 = Female

- Age: 14 = Full out; 16,5 = Maximum ambiguity; 21 = Full in

- Psychological Characteristics (Q2 = Feeling entrepreneur and Q3 = Feel ready to earn own living): 1 = Full Out; 3 = Maximum ambiguity; 5 = Full in

- Entrepreneurship Intentions: 0= Full out (No); 0,5= Maximum ambiguity (Maybe); 1= Full in (Yes). Later, we’ve decided to replace 0,5 by 0,499 to do not lose any observations/cases

Research Design

Based on the literature review, and related variables that may explain how entrepreneurship intentions are formed, we propose to use as the basis of this research the research model (Figure 1).

Results And Discussion

Research intends to explore which factors affect secondary school students’ entrepreneurial intentions, with a focus on the importance of access to a previous entrepreneurship education program, and the influence derived from the type of education they followed, namely regular education or vocational education.

Entrepreneurship intentions is obtained through the students’ answer to the question: “Do you intend to be an entrepreneur?”.

51,2% of students’ valid answers indicated their intentions to become entrepreneurs, while just 8,2% clearly deny this possibility. We notice that 40,5% of the students inquired still had doubts about this end.

To analyse in more detail, the conditions that could have given these preferences, we have developed some cross-tabulations, that allowed us to better understand which were the cases where students opted-in or opted-out from this intention. We found that there are not statistically significant differences between students from vocational and educational training and students from regular education courses concerning their entrepreneurial intentions. Results were confirmed by the chi-squared tests below (0,253) and the p-value (0,881).

We also observed that there are significant statistical differences regarding the influence of previous participation in entrepreneurship educational programs to develop entrepreneurial intentions. Results were also confirmed by chi-squared and the p-values of the statistical tests over these results below 0,002.

Finally results showed also that there are no statistical differences in terms of the entrepreneurial intentions, deriving from gender.

Since one-to-one correlations are not significant to explain entrepreneurial intentions, we opted to study the statistical relations underlying our model in more detail through the use of fsQCA.

fsQCA

The results of the fsQCA allow us to devise some patterns that result in different perceived levels of entrepreneurial intention that are a consequence of different variable combinations applied to the secondary school students. These configurations may provide a view on the conditions that better serve to propel entrepreneurship intentions, which result from the combination of the three dimensions we have used to develop this research: personal, psychological and educational. We use intermediate solutions (Fiss, 2011). No necessary conditions have been found for the absence of the Outcome.

As to the presence of the Outcome, results are as follows:

The 5 possible combinations indicate the following patterns that tend to result in higher entrepreneurial intentions:

-

To attend an entrepreneurship education program improves entrepreneurial intentions on secondary students that did not feel entrepreneurs (Solution 1) or on those that feel already prepared to earn their own living (Solution 2).

-

At the same time, the attendance of an entrepreneurship education program promotes entrepreneurial intentions either in younger female students attending regular education (solution 4) as in older male students in vocational training (solution 5).

-

Finally, it is important to highlight that entrepreneurship intentions are also important in younger female students frequenting the regular educational system that did not consider to be prepared to earn their own living (solution 3).

All the results here presented are statistically significant which means that the referred combinations are important to explain entrepreneurship intentions.

Conclusions

Our results show that entrepreneurship educational programs may influence positively the entrepreneurship intentions of the secondary school students in Portugal, since just one of the possible 5 combinations that render this outcome does not include the attendance of these programs. When compared to other previous research, our results shed light about the real importance of entrepreneurship education programs to propel entrepreneurship development.

We also conclude that entrepreneurship programs have the potential to promote entrepreneurship intentions even when psychological conditions seem to be averse to this end (e.g., do not feel an entrepreneur). Moreover, entrepreneurship education may also have the potential to reinforce entrepreneurial psychological conditions in the case of those students that feel already prepared to earn their own living.

Entrepreneurship education is also important to trigger entrepreneurship intentions in younger female students on regular education, showing the potential to be a kind of “gender unlocking mechanism”, namely when some authors argue that entrepreneurship is more difficult in female entrepreneurs.

Finally, we also observed the importance of entrepreneurship education to reinforce entrepreneurship intentions in older male students from vocational training courses.

Simultaneously, we conclude that when entrepreneurship education programs are able to balance their intervention on psychological characteristics of entrepreneurs with the teaching of useful insights and practical knowledge about the way entrepreneurial ventures need to be managed, they can be important to contradict the usual difficulties showed by both some female to become entrepreneurs, or even the psychological characteristics that may prevent the development of entrepreneurship intentions.

Our results are mostly based on the Portuguese scholar context, and their generalization to other contexts and cultures needs to be done carefully, despite we strongly believe that sample used may be considered generally representative of the secondary school students in Portugal.

In this sense, accordingly to Galindo-Martín et al. (2021), there is extensive literature that analyses the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth (e.g. Acs et al., 2012; Audretsch, 2005; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004a, 2004b; Castaño et al., 2016; Galindo & Méndez, 2014; Méndez-Picazo et al., 2012; Stoica et al., 2020).

“If intention models prove useful in understanding business venture formation intentions, they offer a coherent, parsimonious, highly-generalizable, and robust theoretical framework for understanding and prediction” (Krueger et al., 2000a).