Introduction

Kloutsiniotis and Mihail (2020) assert that franchisors should provide flexible managerial expertise to achieve franchisees’ endeavors and benefits. Essential headquarters’ support recognizes the inherent organizational nature of accelerating successful change in the post-COVID-19 recovery phase (Hsieh et al., 2020). Business relationships between franchisors and franchisees are initiated through a contract in which the standardized agreement provided by the franchisor establishes a business partner relationship. Such contracts are generally considered to be asymmetrical and no different to signing the disclaimer from the franchisees’ perspective (Buchan, 2013). To achieve the intended business performance, the concept of fairness between franchisors and franchisees is a crucial concern. Fairness under the business relationship is imperative for efficiency, as it has a significant impact on the relationship and behavior between signatories. Fairness is a significant concept in terms of business relationships, as it can impact the formation, development, and promotion of efficient relationship processes. Fairness should be carefully considered to establish effective relationships between signatories (Masterson et al., 2000).

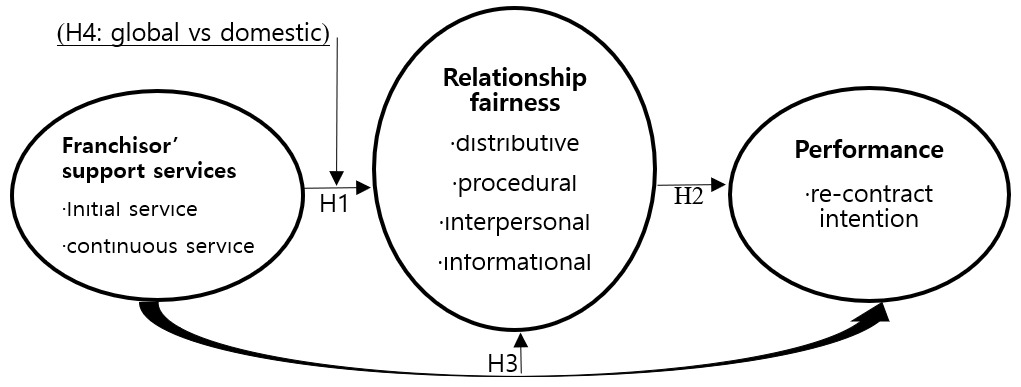

A substantial body of literature considers the concept fairness from various perspectives; however, fairness in cooperative relationships between franchisors and franchisees remains a gray area. Examining distribution channels, Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp (1995) find that providers’ fairness has a positive impact on relationship quality. According to the study, distributive fairness has a positive influence under the distribution channel but is not related to procedural fairness. A number of studies follow regarding the concept of fairness in distribution channel relationships (Liu et al., 2012; Lund et al., 2013; Samaha et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2020). Although the significance of business relationship fairness is widely recognized in marketing and distribution channel literature, empirical conceptualization and practical measurement of the related variables has not yet been extensively investigated (Croonen, 2010; Guilloux et al., 2008), as valid methods to measure fairness between franchisors and franchisees are not yet developed. To address this, we attempt to measure the concept of fairness in the relationship between franchisors and franchisees. This study endeavors to examine the empirical relationship between franchise headquarters’ support service, relationship fairness, and performance, also investigating differences in the impact of support service on relationship fairness between global and non-global franchises.

We seek to construct an appropriate scale for measuring the concept of fairness between franchisors and franchisees to further expand existing inquiry by examining the relationship between fairness and other variables (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001). This study measures fairness in four distinct dimensions of distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness, and support service is distinguished into two categories of initial support (service support prior to starting the business) and continuous support (service support after starting the business). Performance (re-contract intention) includes re-contract, contract extension, and business recommendation.

This study contributes to franchise and business research with three main implications. 1) Examining the mediating effect of relationship fairness will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the crucial factors of the feasibility of franchise headquarters’ initiatives, guidance, and support services, which will aid the verification of franchisees’ ability to execute initiatives. 2) The results of this study can serve as a guideline for franchise headquarters’ development of efficient contract policies that establishes and builds upon relationships between franchisors and franchisees. 3) The findings will enable the establishment of valuable management strategies for recruiting new franchisees, maintaining long-term relationships between franchisors and the franchisees, and energizing business operations.

Theoretical Background and Research Model

Theoretical Background

Restaurant Industry Franchise Headquarters’ Support Service

Franchise headquarters’ support service for franchisees is known to be a significant factor that increases business performance. Previous research demonstrates that systematic and efficient support service from the franchise headquarters can differentiate product and service compared to competitors (Affes & Habib, 2016; E. W. Anderson & Sullivan, 1993; J. C. Anderson & Narus, 1990; Hnuchek et al., 2013).

Appropriate operational and management systems are required to successfully operate a franchise organization, which include supply and distribution of raw materials and product, a franchise start-up process, location selection, educational and financial support, and product development. Multiple support services must be provided to franchisees by franchise headquarters to successfully operate a franchise network, and the characterization of such services varies across researchers. Stern and El-Ansary (1992) distinguishes support services into initial and continuous services, suggesting that initial services include operation system training, initial educational programs for managers, and employee training programs, whereas continuous services include continuing education for managers and employees, new initiatives, and related concerns.

Franchise headquarters’ support services could be a deciding factor in franchisees’ selection of franchisor. Franchisors’ advice prior to opening a store, branding, profit, advertisement (Guilloux et al., 2004), educational training, independency, investment condition (Peterson & Dant, 1990), and rapid growth (Knight, 1986) are found to be the primary selection criteria when potential franchisees are choosing a franchise company. The franchisee selection factors suggested above decrease the risk of operating the new franchise business by running a market verified franchise with continuous services. Franchisees consider such franchises to be a well-known brand that is promoted and already penetrated deeply in consumers’ consciousness (Knight, 1986).

As noted, franchise headquarters’ support services could be classified into prior (initial) support service and post (continuous) support service (Coughlan et al., 2001; Roh & Yoon, 2009; Stern et al., 1996). Prior support service includes market surveys, location selection, interior design and allocation, rental support, financial support, and employee training, whereas post support service includes new products and quality control, field coaching, assistance in retraining, brand strengthening and promotion, operation system support, and supervisor coaching. Although such support is known to improve business performance, previous studies investigating franchisor support predominantly examine marketing mix (Altinay et al., 2014; Asgharian et al., 2012; Hnuchek et al., 2013; Innis & La Londe, 1994; Lewis & Lambert, 1991; Yavas & Habib, 1987.

Relationship Fairness

The concept of fairness from the franchisor–franchisee perspective is studied in two dimensions of justice and fairness in the organizational field (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001) and studies on distribution channels (Brown et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 1995; Lund et al., 2013; Samaha et al., 2011; Shaikh et al., 2018).

The study of fairness in the organizational field originates with Adam’s equity theory, which asserts that perceived fairness determines effort and job satisfaction. In accordance with equity theory, firms compare output in proportion to input with competitors in terms of performance perception. From here, firms predict whether the transaction was fair or unfair in terms of the business partner. Unfairness occurs when firms believe that the proportion of output to input is unfair compared to other related ratios. In contrast, fairness occurs when firms believe that the proportion is fair. Fairness in this respect is considered distributive fairness. Thibaut and Walker (1975) examine the complaining behavior of individuals involved in legal procedures, introducing a novel aspect of fairness using the term procedural fairness. According to the study, people are more interested in the procedure and process than the conclusion or result of the transaction. Leventhal, Karuza, and Fry (1980) expand the concept of organizational structure from legal a perspective using the term procedural fairness. Bies and Moag (1986) conceptualize interpersonal fairness as a third dimension of fairness, focusing on the perceived quality of interpersonal treatment from the others by integrating the procedural method and performance. Greenberg (1990) divides interpersonal fairness into two dimensions of interactional justice and informational fairness. Interactional justice reflects politeness, nobility, and respect to reach the expected result, whereas informational fairness reflects the procedures applied and performance decisions (Greenberg, 1990). Summarizing existing studies, fairness can be categorized into distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness. Table 1 presents an overview of the previous distribution channel studies regarding fairness.

Although a number of studies examine the distribution channel and franchise relationships, previous findings vary and have different perspectives regarding fairness. First, studies about the distribution channel emphasize procedural fairness, disregarding business performance, interaction, and informational considerations in terms of business relationships like distributive fairness (Brown et al., 2006; Griffith et al., 2006, 2006; Kumar et al., 1995; Lund et al., 2013; Narasimhan et al., 2013; Yilmaz et al., 2004). From the organizational perspective fairness is conceptualized in a comprehensive manner, combining distributive, procedural, informational, and interpersonal fairness (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001; Shaikh, 2016; Shaikh et al., 2018). Some studies investigate interpersonal fairness combining interpersonal and informational fairness (Ferguson et al., 2014; Greenberg, 1990).

Second, previous studies examining the fairness factor in the direct and indirect relationships between franchisors and franchisees are extremely limited (Croonen, 2010; Grace et al., 2013; Guilloux et al., 2008). Croonen (2010) approaches fairness quantitatively, whereas Grace et al. (2013) do not directly measure fairness but contend that fairness affects performance and the nature of the relationships between franchisors and franchisees.

Third, considerable existing research has not yet constructed reliable measures of the fairness between franchisors and franchisees. Liu et al. (2012) and Narasimhan, Narayanan, and Srinivasan (2013) apply a limited approach of measuring informational and interpersonal fairness from the perspective of interactional fairness. Shaikh (2016) validate a measure of fairness in the context of the franchisor–franchisee relationship to test the dimensionality of fairness. Their findings suggest that the structure of fairness is a three-factor correlated model including aspects of both procedural and informational fairness in one construct.

Relationship fairness in franchising firms can be categorized into four types, in which the distributive, procedural, and informational aspects of fairness are structural, whereas interpersonal fairness is the sole social aspect of relationship fairness.

(1) Distributive fairness

From a marketing perspective, distributive fairness is about the structural aspects of the marketing system that determine how to fairly distribute rewards and penalties to subjects during business transactions and how to execute policies (Laczniak & Murphy, 2008). Distributive fairness in the distribution channel relates to perceptions of fair profit from the provider as a result of performance or a particular investment (Kumar et al., 1995). This is measured by examining how transaction fees are applied under the distribution channel and how profits are shared (Kumar, 1996). Our study adopts franchisees’ perception of fairness in terms of earnings and outcomes received relative to the franchisee’s efforts and investment in the exchange relationship with the franchisor (Shaikh, 2016).

(2) Procedural fairness

Procedural fairness in the franchise distribution channel relates to product distribution and procedure, fairness regarding price, and promotional support. Procedural fairness also includes the provision of appropriate products and services (D. S. Johnson & Moran, 2018) and the duties performed by and expectations of the salesperson on behalf of the organization. In sum, procedural fairness relates to the fairness of the policies and procedures conducted by related firms (Greenberg, 1990). Our study adopts franchisees’ perception of fairness regarding franchisors’ policies and procedures, which impacts distribution of outcomes in the franchisor–franchisee relationship (Shaikh, 2016).

(3) Interpersonal fairness

Business between franchisors and franchisees occurs through the establishment and maintenance of the relationship. Franchisors’ treatment of franchisees influences franchisees’ perceptions of fairness. This is the concept of interpersonal fairness. In short, interpersonal fairness refers to franchisees’ perception of fairness of the quality of interpersonal treatment received from franchisors’ representatives (Shaikh, 2016).

(4) Informational fairness

Informational fairness refers to the timeliness of a business partner’s provision of relevant information, proper explanation of chosen procedures, and the manner in which they engage in communication (Ferguson et al., 2014). The franchisee that is in business relationship with the franchisor expects to communicate in an efficient way regarding the product, market, and competitors to achieve satisfactory results. Subsequently, as interpersonal fairness refers to the interpersonal treatment received during a transaction, informational fairness is the requisite, timely, and relevant information shared by the franchisor as expected by the franchisee (Shaikh et al., 2017).

Performance (Re-contract intention)

Re-contract intention in the franchise system can be considered a reflection of franchisees’ satisfaction or displeasure with the franchisor and can be measured by willingness to renew a contract, whether they are subject to the priority of the contract, and recommendations to other potential franchisees. It is also about whether to maintain or cease business with the franchisor in terms of performance and satisfaction from the franchise business. A substantial body of literature examines the factors influencing franchisees’ re-contract intention. Stern and El-Ansary (1992) assert that as the commitment strengthens, renewal intention will increase and could contribute to competitive advantage over competing franchise firms.

In a study using renewal intention as a dependent variable, Oliver (1999) asserts that the crucial determinant of business contract renewal is not merely satisfaction, but actual performance should also be considered. Other studies demonstrate that an unstable market environment, regular reinvestment, reputation, business performance, and mutual satisfaction are significant influences on re-contract intention (Dickey et al., 2007; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ganesan, 1994).

Chiou, Jyh-Shen, Hsieh, Chia-Hung, Yang, and Ching-Hsien (2004) examine the relationship between the intention to retain a franchise and overall satisfaction among convenience stores in Taiwan. The results indicate that competitive advantage and communication have a significant impact on satisfaction and trust; however, franchise headquarters’ service support is not shown to have a significant direct effect on overall satisfaction. Intention to continue a franchise (renewal intention) is measured by positive word-of-mouth and resistance to change (Chiou et al., 2004). Abdullah, Alwi, Lee, & Ho (2008) define five dimensions that affect franchise renewal, including interaction with the franchisor, service support from the franchisor, finance, self-confidence, and the ability to compete, asserting that service support and the ability to compete have significant impact on re-contract intention.

Research Framework and Hypotheses

Research Framework

The research model presented in Figure 1 examines the mediating effect of relationship fairness between franchisors’ support service and re-contract intention, and a mean differences test is conducted to analyze whether there is a significant difference between global and the non-global franchises.

The independent variable (support service from the restaurant franchisor), dependent variable (re-contract intention), and mediator (relationship fairness) are based on previous studies and the indicators were verified via pilot test and interviews with related stakeholders (franchisors and franchisees) and experts (researchers, officials, and organizational associates).

Our proposed research model of relationship fairness could help managers understand and manage franchise relationships more effectively. This research framework can also be used to examine the perceived relationship fairness of franchisors’ support services and actual relationship outcomes (performance).

Hypotheses

This study assigned relationship fairness as a mediator, franchisors’ support service as an independent variable, and franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention) as a dependent variable using the research model shown in Figure 1.

Previous studies regarding franchise relationships only stress procedural fairness, disregarding business performance, interaction, and informational considerations (Brown et al., 2006; Griffith et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 1995; Yilmaz et al., 2004). Studies regarding the direct and indirect relationship between franchisors and franchisees that include the concept of fairness are significantly limited (Croonen, 2010; Grace et al., 2013; Guilloux et al., 2008). Based on this critical research gap, and the research framework presented, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1. Restaurant franchisors’ support service positively influences relationship fairness between franchisors and franchisees.

H1-1. Restaurant franchisors’ initial support service positively influences relationship fairness between franchisors and franchisees.

H1-2. Restaurant franchisors’ continuous support service positively influences relationship fairness between franchisors and franchisees.

From an organizational perspective, the concept of fairness is treated in a comprehensive manner, combining distributive, procedural, informational, and interpersonal fairness (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001). Others examine interpersonal fairness combining interpersonal and informational fairness (Ferguson et al., 2014; Greenberg, 1990). Although Grace et al. (2013) do not directly measure fairness, the authors assert that fairness in franchises affects performance and the relationship between franchisors and franchisees.

Considering the above discussion, we formulate the following hypotheses to test whether the franchisees’ fairness perception regarding franchisors’ support service has an effect on renewal intention.

H2. Relationship fairness between restaurant franchisors and the franchisees positively influences franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

H2-1 Distributive fairness positively influences franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

H2-2. Procedural fairness positively influences franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

H2-3. Interpersonal fairness positively influences franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

H2-4. Informational fairness positively influences franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

Research investigating the factors that influence franchisees’ renewal intention as a dependent variable demonstrates that the crucial determinant of business contract renewal is not merely related the franchisees’ satisfaction, but actual performance should also be considered (Oliver, 1999). Some studies assert that an unstable market, regular reinvestment, reputation, business performance, and mutual satisfaction have significant impact on contract renewal (Dickey et al., 2007; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Ganesan, 1994). Chiou et al. (2004) demonstrate that franchisor support does not have a direct effect on franchisees’ overall satisfaction, and Abdullah et al. (2008) identify interaction with the franchisor, service support, finance, confidence, and the ability to compete as the five crucial factors that influence franchisees’ renewal intention. Considering preceding studies, the mediating effect of relationship fairness between franchisors’ support service and franchisees’ re-contract intention remains a gray area. Based on previous findings, the following hypotheses are proposed to investigate this mediating effect.

H3. Franchisors’ support service has an indirect effect on franchisees’ re-contract intention through relationship fairness.

H3-1. Franchisors’ initial support service has an indirect effect on franchisees’ re-contract intention through relationship fairness.

H3-2. Franchisors’ continuous support service has an indirect effect on franchisees’ re-contract intention through relationship fairness.

The globalization of franchising firms represents a tremendous opportunity to pioneer into new markets, resulting in new value and considerable growth (Lu & Beamish, 2001). Global franchise companies are accelerating overseas expansion as they experience saturation in domestic markets (Hoffman & Preble, 2004). Among the Top 500 franchises in the US, 80% have established stores overseas via direct management or as affiliated stores, and a significant number of those companies now have more stores overseas than in the domestic market (http://www.entrepreneur.com/franchises/franchise500). Franchises extended business in developed countries in Europe and in Japan in the early stage of overseas expansion and are now entering emerging markets such as Southeast Asian countries, Russia, Brazil, and Vietnam.

Global franchises bolster competitiveness by providing outstanding resources and practical knowledge to overseas franchisees and acquiring new resources and knowledge from the franchisees also strengthens global competitiveness (Jonsson & Foss, 2011). It is crucial for global brands to obtain local market information from franchisees because they are not equipped to fully understand the circumstances abroad; thus, global franchises can develop more sophisticated and systematic operation and information exchange systems compared to non-global franchises through sharing advanced resources and acquiring local information from franchisees. Global franchises are assumed to have operational and information exchange systems that are superior to domestic franchises, which can lead to less obstacles in terms of relationship fairness. Moreover, if an issue arises between two parties, they will be able to address the matter through smooth communication using an integrated approach rather than a distributive approach. Considering the above discussed postulations, we formulate the following hypothesis.

H4. The impact of restaurant franchisors’ support service on relationship fairness differs between global and non-global franchises.

Methodological Procedures

Definition of Variables

Franchisor’s support service

Previous studies about franchisor support service are primarily conducted in terms of marketing mix (Altinay et al., 2014; Asgharian et al., 2012; Hnuchek et al., 2013; Innis & La Londe, 1994; Lewis & Lambert, 1991; Yavas & Habib, 1987). As noted previously, research distinguishes support service into prior (initial) and post (continuous) categories (Coughlan et al., 2001; Roh & Yoon, 2009; Stern & El-Ansary, 1992). Prior support service includes market surveys, location selection, interior design and allocation, support for store rental, financial support, and employee training, whereas post support service includes new products and quality control, field coaching, assistance in retraining, brand strengthening and promotion, operation system support, and supervisor coaching.

Relationship fairness

As previously introduced, the two perspectives of relationship fairness studies include organizational studies (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001) and distribution channel analyses (Brown et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 1995; Lund et al., 2013; Samaha et al., 2011; Shaikh et al., 2018). Research on relationship fairness can be categorized into distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness.

In this study, distributive fairness refers to franchisees’ perception of the fairness of the profit received from franchisors as a result of effort or a particular investment. Procedural fairness is measured by franchisees’ perceptions of the policies and procedures provided by the franchisor that influence performance and distribution. Referencing Blodgett et al. (1997), we measure interpersonal relationship fairness as franchisees’ perception of the fairness of the franchisors’ representative. Based on previous studies (Ferguson et al., 2014; Greenberg, 1990), informational fairness is franchisees’ perception of fairness regarding the franchisors’ business, product, procedure, performance, and information.

Performance (Re-contract intention)

Extant studies regarding performance measurement include both financial and non-financial factors. This study examines the impact of relationship fairness to performance based on re-contracting, priority contracts, and recommendations.

Measurement and Analysis of Variables

Independent variables are measured by distinguishing support service into initial and continuous support service, and re-contract intention (dependent variable) measures the contract renewals with franchisors, priority subject to the contract, and recommendations.

Relationship fairness is constructed and tested based on variables in existing literature and a current survey questionnaire for generalization and conceptualization. We primarily examined preceding studies regarding relationship fairness to extract the factors. We then conduct interviews with restaurant franchise executives that subsequently reflect the extraction of the factors. Through the screening process, we narrowed and revised overlapping and similar concepts. Finally, we constructed a survey to examine our research model using a 5-point Likert scale to measure perceptions of support service, relationship fairness, and performance. The survey also included general characteristics of restaurant franchises and demographic information.

Data collection and Analysis

The subject of this study is the restaurant industry, which accounts for the largest proportion among business-type franchises. Restaurant franchise headquarters registered with the Korea Franchise Association and the Korea Franchise Business Association were selected and further research was conducted on franchisees. The convenience sampling method was used for franchise owners operating franchise stores in Seoul and Gyeonggi regions to minimize the cost and time of sampling. The survey was conducted via telephone interview, email, and in-person researcher visits. A total of 205 questionnaires were collected and four unusable questionnaires containing extreme errors and outliers were excluded (201 total).

To ensure the reliability and internal consistency of the measurement model, we adopted SPSS (V.25) and derived Cronbach’s alpha. We also conducted confirmatory factor analysis using the AMOS (V.25) program to assess the unidimensionality of measurements. Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test our hypothesized research framework.

Empirical Analysis

Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 2 presents the data of the respondents’ characteristics. The sample of global and non-global franchises used for comparison were collected in similar proportion. The largest number of the franchisees’ monthly sales ranged from 2,000,000 KW to 5,000,000 KW, at 19.9%, and monthly sales ranging from 5,000,000 KW to 10,000,000 KW were at 15.9%. Most of the franchisees had two to five employees per store, which was a small number. In terms of previous experience, 45.7% of respondents had previous experience operating a franchise or restaurant business, whereas 54.3% had no experience. Also, 45% responded that they had business experience as a franchisor less than five years and 44% responded that they had business experience of five to 10 years. This indicates that although they lack wide experience and accumulated knowledge and skills, nearly half of the respondents had experience in a franchise business.

Reliability tests

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to examine the internal consistency of items measured in the survey. Generally, the acceptable values range from .70 to.95 (Kerlinger, 1973). To test the reliability of the indicators used in this study (franchisor support service, relationship fairness, and performance), we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha of each variable. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, most of the scores exceeded .80, which is a satisfactory level; thus, the measurement scales adopted in this study are reliable and the statistical analysis used to examine our conceptual framework is logically acceptable.

The average value extract score (AVE), ranging from .51 to .56, also reached the acceptable limit of .5 (Hair et al., 2005) and the square root of the AVE was higher than the correlation between each construct indicating adequacy. Moreover, the value of composite reliability, which determines the internal consistency of multiple indicators, ranges from .76 to .86, which also exceeds the acceptable limit of .6, implying adequate discriminant validity (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988).

Validity tests

To assess the unidimensionality of each variable, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 25. The composite reliability (CR) scores for most of the variable exceeded .70 and AVE scores also exceeded .50 (Fornell, 1992), indicating that unidimensionality is not a hinderance. When the squared value of the correlation coefficient score of each variables exceeds the AVE score, this indicates adequate discriminant validity (Fornell, 1992). As shown in Table 6, the current research model clearly indicates sufficient discriminant validity.

Results and Findings

Evaluation of research model

Table 7 summarizes the standardized structural estimates and multiple group analysis of the current research framework via AMOS 25. The maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method was used to estimate the parameters. MLE estimates the most probable parameter by maximizing the likelihood function. Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the Goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the Adjusted Goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), the Comparative fit index (CFI), the Incremental fit index (IFI), and root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). Overall indices were above the acceptable level indicating a good fit.

Hypothesis testing

The result of the hypotheses test examining the impact of support service on relationship fairness and performance is presented in Table 7. First, H1 was used to explain the relationship between franchisors’ support service and franchisees’ perceived relationship fairness. In terms of initial support service, the estimations revealed that the mean coefficient of procedural fairness was positive and statistically significant (β=.380, t=4.215, p<.01). Also, in contrast to distributive fairness (β=.033, t=.055, p>.1), initial support service had positively significant impact on interpersonal fairness (β=.223, t=3.055, p<.01). Therefore, H1-1 was partially supported. Continuous support service was also found to affect distributive fairness significantly and positively (β=.789, t=7.507, p<.01), procedural fairness (β=.427, t=4.668, p<.01), interpersonal fairness (β=.223, t=3.055, p<.01), and informational fairness (β=.797, t=7.507, p<.01), supporting H1-2. Consequently, relationship fairness (distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness) improves when franchisors provide satisfactory (initial and continuous) support service. Our results indicate that continuous support service has a more influential effect compared to initial support service; thus, to respond to the needs of the franchise industry and establish a competitive edge, franchise headquarters should improve support service to franchisees and maintain an effective quality improvement and operational systems.

H2 was proposed to examine franchisees’ perceived relationship fairness with franchise headquarters. The results demonstrated a positively significant impact from procedural fairness (β=.144, t=1.771, p<.10) and informational fairness (β=.451, t=4.173, p<.10) on franchisees’ re-contract intention, partially supporting H2. This suggests that information sharing between franchisors and franchisees should be expanded by following a formal and consistent procedure to raise franchisees’ performance (re-contract intention).

H3 was proposed to investigate the mediating effect of relationship fairness between restaurant franchisors’ support service and performance (re-contract intention) (Table 8), which was conducted via bootstrapping and a Sobel test to identify the indirect path. Analyses indicated that there was a possible mediating effect of relationship fairness between initial service support and performance (re-contract intention); however, no significant mediating effect was revealed, except for informational fairness. Similarly, only informational fairness had a partial mediating effect between continuous support service and performance. Subsequently, our results suggest that franchisors’ support service has a positive indirect effect on re-contract intention through relationship fairness. It was confirmed that strengthening the role between the franchisor and the franchisee and strengthening the authority to access information is an important factor in increasing franchisees’ psychological experience of ownership, referring to the members’ sense of belonging to an organization (Rousseau & Shperling, 2003), and enhances the sense of unity with the organization (Pierce et al., 2001). Considering the future growth potential of the restaurant franchise industry, informational fairness between the franchisor and the franchisee must be emphasized and strengthened. In addition, continuous system improvement is needed to achieve and maintain competitive advantage, and ongoing development of the franchise program through mutual communication should be encouraged.

Finally, H4 was hypothesized to investigate potential differences in the impact of support service to relationship fairness between global and non-global franchises. Our results indicated no differences in the initial support service between global and non-global franchises. Conversely, in terms of continuous support service, global franchises had greater impact than non-global franchises. In other words, the impact of continuous support service on relationship distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness was greater in global franchises. The effect of relationship fairness to re-contract intention was not statistically significant between two groups. However, distributive fairness and informational fairness were found to be significant factors of re-contract intention in global franchises and interpersonal fairness had significant impact on performance in both groups.

Discussion and Implications

This study investigated whether relationship fairness has a mediating effect between franchisors’ support service and performance (re-contract intention), with implications for supporting the mutual growth of franchisors and franchisees and the potential for franchise restaurants in Korea. Hypothetical testing adopted SEM to examine the mediating effect of relationship fairness between franchisors’ support services and re-contract intention to investigate the differences between global and non-global franchises.

Our findings provide extensive insights for franchise businesses and introduces new considerations for franchise research.

First, according to the results from H1, although all of the relationship fairness variables were statistically significant in terms of continuous support service, in the case of initial support service, distributive fairness was not significant, so the hypothesis was partially accepted. As shown in Table 7, initial support service had significant impact on other fairness sectors, excluding distributive fairness. This finding could be interpreted as improved restaurant franchisor support service resulting in franchisees’ perceiving higher relationship fairness. Specifically, since continuous support service is shown to be more influential compared to initial support service, franchise headquarters should improve the service quality of continuous support and consistently upgrade and renew support programs. This study’s results indicate that in the ranking of importance (ongoing support, possibility for development, and franchisor’s advertising efforts), less importance is given to the profitability dimension of the criteria employed in selecting franchisors, which has evolved over time and new aspects are emerging (Guilloux et al., 2004).

H2 demonstrated the significant positive impact of procedural and informational fairness on franchisees’ re-contract intention. This signals that sharing relevant information between the franchisor and the franchisee should be conducted transparently and efficiently by consistently following a prescribed procedure. When a franchise fully leverages the distributive and interpersonal fairness that underlies this context, there will be higher chance of re-contract.

Third, regarding H3, only informational fairness had a partial mediating effect between continuous support service and performance, partially supporting the hypothesis. The results indicate that franchisors’ initial and continuous support service has a positive indirect effect on re-contract intention through relationship fairness. Considering the future growth potential of the restaurant franchise market, franchise companies should adequately leverage informational fairness when developing a new product (service) due to changes in consumers’ life cycle and brand perceptions.

Finally, our results from H4 demonstrated a difference in the impact of continuous support service to relationship fairness between global and non-global franchises. Since global franchise’s continuous support service seems to have a greater effect on relationship fairness, following Jonsson and Foss (2011), global franchises can increase competitiveness through the continuous development of outstanding resources and practical knowledge to overseas franchisees. As this level of support will eventually lead to improved and sustained performance, the franchisor’s continuous service is crucial.

Recently, as the restaurant franchise market is experiencing significant growth, government and franchise-related agencies are making considerable effort to improve the relationships between franchisors and franchisees, and to develop improved systems and policies concerning consumer protection. Government and franchise agencies are encouraged to develop adequate policies to improve the relationships between franchisors and the franchisees by breaking away from imprudent support. This requires the FTC Franchise Rule (USA), in which the franchisor has the authority and considerable control over the franchise business, and it is also necessary to refer to the EFF Code of Ethics (EU), which conducts business according to the concept established by the franchisor.

Two implications and potential future studies could be derived from our findings. First, franchisors’ initial and continuous support services increased franchisees’ overall perception of fairness. This result indicates that continuous maintenance, review, and upgrade of the support service provided initially by the franchise headquarters is a crucial determinant of franchisees’ perception of relationship fairness. Through regular investigation, franchise headquarters should be responsible for developing and renewing appropriate manuals to examine whether the manual is being executed as promised and make changes as needed.

Second, in terms of the relationship between franchise headquarters’ support service and performance, relationship fairness had a mediating effect between two variables. This suggests that for sustained development and increased competitiveness in the restaurant franchise industry, mutual communication between the franchisor and the franchisee and mitigation of information asymmetry is essential. Our findings also suggested that procedural fairness is another crucial determinant of re-contract intention. Consequently, franchisors should provide adequate support service regarding manual and business policies to decrease information asymmetry, leading to increased procedural fairness and performance (re-contract intention).

While this study contributes to existing franchise literature, it has several limitations which open avenues for future research. First, there are limitations in the variability and range of the sample. During the survey process, franchise size and franchise business experience items were slightly skewed. Furthermore, as the survey was conducted in a short time frame, there could limitations in sample variability. Second, since this study was conducted across the restaurant franchise industry, it is difficult to generalize our findings to the overall franchise industry. Future studies could extend the research by exploring other franchise industries, such as distribution, retail businesses, and service industries. Third, the survey questionnaire used in this research was based on existing studies; thus, a more concrete survey, developing the survey questions from a wider perspective could expand the current research. Finally, additional research is needed to examine the franchisor–franchisee relationship, which is considered a structural characteristic of franchise business. The interactions between franchisors and government policy regarding franchise businesses is also another exploration to further enrich the field.