Introduction

Innovation and entrepreneurship are inextricably linked and complementary in helping organizations thrive in dynamic environments (Mendez-Vega et al., 2021; F. Zhao, 2005). “Entrepreneurship, in its narrowest sense, involves capturing ideas, converting them into products and, or services and then building a venture to take the product to market” (Johnson, 2001, p. 138). To better understand the source of innovations, social scientists have discovered fundamental differences in thinking patterns that influence how individuals scan, interpret, and react to information in their environment as they build mental models to inform behavior (J. Hayes & Allinson, 1998). For example, cognitive styles have been recognized as a core facet of creativity and innovation (Scott & Bruce, 1994; Tierney et al., 1999; Woodman et al., 1993). Innovative individuals use a more intuitive rather than systematic problem-solving approach (Scott & Bruce, 1994). They are more intrinsically motivated (Tierney et al., 1999) and willing to take initiative to promote their ideas (Miron et al., 2004). Entrepreneurs tend to apply a more innovative cognitive style than managers of larger companies (Stewart et al., 1999).

In organizational settings, researchers have identified personal characteristics that make individuals more apt to identify and act on new business opportunities (Ahimbisibwe et al., 2021). For example, entrepreneurs are more inclined to be risk takers and apply an individualistic approach toward the work environment (Antoncic et al., 2018; McGrath et al., 1992). Strong interpersonal skills are vital to key entrepreneurial activities, such as making a pitch to investors (Clark, 2008). Entrepreneurs are very passionate about their work and prefer to take action rather than be complacent (Cardon et al., 2009; Y. Lee & Herrmann, 2021). They have resilient personalities that help them to overcome obstacles (Vizcaíno et al., 2021). Successfully acquiring and integrating new information is fundamental to the innovative process (Grant, 1996; Zhou & Li, 2012), and entrepreneurs who deliberately search for new information (via knowledge creation) and successfully integrate that information (via knowledge transfer) into their business strategies show greater innovative performance (Donate & Sánchez de Pablo, 2015). Recent research has investigated the role of maximizing or satisficing decision strategies in entrepreneurial performance, finding that those who maximize their decisions by seeking out more options to find the best outperform those who satisfice their search strategies by settling for good enough options (Soltwisch, 2021).

Dating back to the 1950’s, the concept of satisficing was originally developed by Herbert Simon to describe how individuals have limited capacity to process all relevant information when attempting to make rational decisions. In his theory of bounded rationality, Simon proposed that due to time constraints and cognitive limitations, it isn’t possible for humans to consider all decisional outcomes in a way that would allow them to make reasoned decisions (Simon, 1955) In this way, satisficing behavior (i.e. seeking out satisfactory solutions rather than optimal ones) was initial proposed as a bi-product of individuals’ cognitive limitations as they face overwhelming amounts of information. The concept of maximizing and satisficing has since been redefined by Schwartz and colleagues (2002) as a measurable trait in which individuals differ (Schwartz et al., 2002). They identified that some individuals consistently strive to make the best choice by searching intensively (maximizers), while others are more inclined to select options that are good enough (satisficers). For example, when buying a new computer, a maximizer may spend additional effort to read reviews and compare models to find the best one. Alternatively, satisficers are more likely to select the first computer that meets their minimum standards rather than continuing their search to see if there may be something better available. This new measure of differences in decision-making styles (maximizing or satisficing) has been linked to a variety of personal and organizational outcomes (see Highhouse et al., 2008; Lai, 2010; Misuraca et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2002; and Cheek & Schwartz, 2016, for review).

Researchers have begun to investigate these differences in the context of work behaviors and career choices, finding that maximizers’ intensive search strategies pay off in landing higher paying jobs (Iyengar et al., 2006) and discovering positions that are better aligned with their values, leading to greater career commitment and satisfaction (Voss et al., 2019). The maximizing concept has recently been applied to the study of entrepreneurs, finding that those who maximize their decisions use their preference for information search to build more entrepreneurially oriented businesses. As a result of this increased attention to their external environment, they are able to recognize and integrate new opportunities into their business strategy in a way that produces greater financial performance (Soltwisch, 2021). Yet, it is unclear how these approaches to information search may influence an individual’s propensity to recognize opportunities to innovate and launch new ventures in the first place. Therefore, this study aims to answer the following research questions. Does an individual’s propensity to maximize their decisions influence their entrepreneurial intentions? How does a maximizing style affect a person’s innovation behavior, entrepreneurial alertness, and opportunity attractiveness? And do these factors mediate the relationship with entrepreneurial intentions? It is predicted that maximizers will have greater entrepreneurial intentions. Underlying this effect, it is proposed that maximizers will report greater innovation behavior, entrepreneurial alertness, and opportunity attractiveness. The theoretical basis for the research model is developed in the next section based on the extant literature.

To test the model, a survey is conducted with 253 working professionals who respond to previously validated measures. Multiple regression and mediation analysis are used to test the hypotheses. To further understand the underlying process, a second study is undertaken to investigate how maximizers or satisficers evaluate a specific opportunity, and how their evaluation of the opportunity influences their intentions to become entrepreneurs. The second study also serves to replicate the main effects of the first study in a unique sample of 192 university students. Finally, results and implications to the field are discussed in relation to the current findings.

Theoretical Framework

Maximizing and Satisficing

Maximizers apply more time and effort to the decision-making process (Polman, 2010; Schwartz et al., 2002). In doing so, they consider more options (Chowdhury et al., 2009), engage in more comparisons of options (Schwartz et al., 2002), and identify more positive and negative consequences of each outcome (Polman, 2010). They are even willing to give up resources to obtain access to more alternatives (Dar-Nimrod et al., 2009). Their quest for the best does not always make them happy, however, as they often end up less satisfied with their decisions due to looking at what could have been rather than what is (Iyengar et al., 2006; Schwartz et al., 2002). Because they take a “grass is greener on the other side of the fence” perspective, maximizers experience more post decision regret than satisficers (Parker et al., 2007; Purvis et al., 2011; Schwartz et al., 2002). This dissonance is produced by worrying about missing out on unexplored but potentially better options (Iyengar et al., 2006). Because of this, maximizers are more perfectionistic (Bergman et al., 2007), less optimistic (Schwartz et al., 2002), more neurotic (Purvis et al., 2011), and more likely to procrastinate (Osiurak et al., 2015).

Although maximizers constant quest for the best may cause them to experience more negative psychological traits than satisficers, there is some evidence that their decision efforts pay off with better decision-making outcomes. In a study of the career search process, it was found that maximizers searched for more job opportunities and landed jobs with starting salaries of $7,500 higher than satisficers on average (Iyengar et al., 2006). Interestingly, they were less satisfied with those better paying opportunities because of their higher expectations based on past achievements. By creating larger option sets to choose from, maximizers experienced more instances of regret based on their knowledge of missed opportunities along the way (Iyengar et al., 2006). As they are constantly on the lookout for better options, those who maximize in their careers find roles that are a better fit with their personal values and show greater commitment to their profession (Voss et al., 2019). There is some evidence that maximizers may make more ethical decisions as they see ethical dilemmas through an idealistic perspective (Soltwisch et al., 2020). Maximizers find decision-making activities enjoyable and feel more adept in their ability to make good decisions (Lai, 2010). They are more willing to put in additional effort toward finding the best outcomes for themselves and others. For example, executives who maximize report putting in more time and energy in their pursuit of better outcomes for the company (Lai, 2010). Maximizers not only attempt to optimize outcomes for themselves, but they attempt to maximize outcomes for others around them. In a study of gift purchasing behavior, maximizers (vs. satisficers) spent extra time and effort to find the best gift for a friend and were more likely to switch the gift if something better was available (Chowdhury et al., 2009).

Traditionally measured as a continuous variable, satisficing and maximizing are the opposite ends of a spectrum of decision-making tendencies that people exhibit as they approach choice. Instead of searching extensively to find the best option, satisficers will stop their search efforts when they locate an option that meets their minimum standards (Schwartz et al., 2002). Essentially, they will go with an option that is “good enough” rather than continuing to search for something better. For example, when shopping for a new phone, a satisficer is more likely to stop their search after finding a model that meets their desired specifications (say a large screen and affordable price) rather than continuing to visit other stores to compare models to see if they can find something better. Because of this, satisficing consumers are less affected by additional product features (Brannon & Soltwisch, 2017). When it comes to careers, satisficers do not explore as many opportunities and are more likely to focus on options that fit within their existing knowledge base (Iyengar et al., 2006). Yet, satisficers are more likely to be the “happy go lucky types” that, despite potentially missing out on better opportunities due to their amenable search efforts, have greater life satisfaction because they don’t share the same propensity as maximizers to compare themselves with others who are doing better than them (Schwartz et al., 2002; Weaver et al., 2015).

Maximizing and Entrepreneurial Intentions

Entrepreneurs are constantly looking for opportunities to turn ideas into new products or services that add value in the marketplace (Baron & Ensley, 2006). This is accomplished by launching new businesses or through corporate entrepreneurship (Schumpeter, 2000). Their efforts are the result of planned actions and intentions (Krueger et al., 2000), which have been a reliable predictor of entrepreneurial behaviors (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006; Wu, 2009). Because entrepreneurs are made and not born (Boulton & Turner, 2006), researchers have identified general trends in personal characteristics associated with pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities. For example, entrepreneurs tend to be proactive rather than reactive (Koe, 2016), more innovative (Bolton & Lane, 2012), and tolerant toward risk (Yurtkoru et al., 2014). They are passionate about their work (Cardon et al., 2009) and rely on finely tuned interpersonal skills to interact with others effectively (Clark, 2008; Dias & Silva, 2021).

According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), entrepreneurial intentions would be an indication of the effort an individual is willing to make to carry out entrepreneurial behaviors. There have been a growing number of studies investigating how experiences impact entrepreneurial intentions. For example, research suggests that prior family experience (Carr & Sequeira, 2007) and entrepreneurial exposure (Gird & Bagraim, 2008) are significant predictors of one’s intent to become an entrepreneur. Taking entrepreneurship courses also increases entrepreneurial intentions (Elmuti et al., 2012; Liñán et al., 2011; Lüthje & Franke, 2003; Pittaway & Cope, 2007). Interestingly, entrepreneurial education may have a greater influence on women than it has on men. Even though men tend to have higher entrepreneurial intentions overall, women are more likely to improve their entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions by taking classes (Wilson et al., 2007). The diversity of the learning environment may also be influential, as those who are exposed to new ideas and perspectives through diverse campuses show greater intentions to become entrepreneurs (Haddad et al., 2021).

Other researchers have focused on individual differences in entrepreneurial intentions, finding that conscientiousness (Engle et al., 2010), self-efficacy (H. Zhao et al., 2005), need for achievement (Tong et al., 2011), risk tolerance, and internal locus of control (Segal et al., 2005) are associated with one’s intent to become an entrepreneur. Organizational factors are also important in encouraging individuals to pursue entrepreneurship as a career path. Generally, those who are dissatisfied with their job show higher entrepreneurial intentions. A study of IT professionals found that low job satisfaction was a significant predictor of entrepreneurial intentions (L. Lee et al., 2011). Interestingly, the study found that those who are more innovative and confident in their abilities were more likely to pursue entrepreneurship as a result of feeling constrained by their overly restrictive work environment. It is not surprising that innovative individuals find constricted work environments unsatisfactory, leading them to find other outlets to exercise their creative potential.

Maximizers find decision-making activities enjoyable and feel more competent in their abilities to choose (Lai, 2010), which may encourage them to explore new ideas on their own terms. Maximizing has also been linked to various leadership traits. For example, executives who maximize report putting in more work as they strive for the best possible outcomes (Lai, 2010). Among managers, there is some evidence that the maximizing trait may lead to greater effectiveness (Soltwisch & Krahnke, 2017). In addition, maximizers may find it appealing to be their own boss because they prefer to have control over the decision-making process (Sparks et al., 2012). Their preference to control the decision-making process combined with their quest to explore new and better alternatives may motivate them to lead the innovation process by starting their own businesses.

There is some evidence that a maximizing style may be beneficial to the entrepreneurial process. A recent study found that entrepreneurs who maximize their decisions built more entrepreneurial and market-oriented businesses that explore and integrate new external opportunities into their business strategies in a way that meets changing market demands, leading to greater financial success (Soltwisch, 2021). Interestingly, entrepreneurs who maximize their search strategy create policies and procedures that enable strategic flexibility within their businesses. Since entrepreneurship starts with an opportunity (Morris, 1998), it is not surprising that exploring opportunities in the environment and being proactive in advancing them is beneficial to the success of launching new ventures (Kusa et al., 2021).

In the work setting, maximizers, who exhaustively search for better alternatives, may desire to pursue business opportunities on their own terms. The work environment itself may serve as a push factor encouraging them to consider an alternate career path. For example, maximizers are generally less satisfied in the workplace and more likely to quit their jobs to find something better (Giacopelli et al., 2013). Since maximizers are more affected by social comparisons, especially with those who are doing better (Schwartz et al., 2002; Weaver et al., 2015), the traditional career ladder may leave them discouraged as they perceive the disparity between their ranks and those who are more successful. Their constant search for better options often leaves them with feelings of regret because they may have missed out on unexplored but potentially superior opportunities (Schwartz et al., 2002). They also experience what is commonly referred to as fear of missing out, or FOMO for short (Servidio, 2021). As a result, they may attempt to avoid any anticipated regret by acting on opportunities as they come up.

A study that followed university students over the course of a year after graduating found that those who maximize (vs. satisfice) utilized more external sources of information to search for more realized and unrealized job opportunities, eventually landing positions with 20% higher starting salaries on average (Iyengar et al., 2006). Interestingly, they were less satisfied with those jobs even though they were objectively better. This feeling of dissatisfaction after making a choice can be linked to their constant struggle to find better options. Maximizers’ proclivity toward extensive search may allow them to identify more entrepreneurial prospects, and their quest to be the best may encourage them to pursue those opportunities.

Satisficers, on the other hand, tend to accept something that meets their minimum criteria, and are likely to ignore additional options when they have found something that is good enough (Schwartz et al., 2002). They are more satisfied with their life choices overall as they experience less regret from missing out on potentially better opportunities (Parker et al., 2007). In the job search process, satisficers search for fewer opportunities and rely on less external information to inform their decisions (Iyengar et al., 2006). Interestingly, even if they land lower paying jobs than maximizers, satisficers feel better about those jobs because they don’t consider what they may have missed. Because satisficers tend to be more content with their careers overall (Giacopelli et al., 2013) and less likely to consider other options (Iyengar et al., 2006; Parker et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2002), they may be less likely to see entrepreneurship as an alternative career path. Comparatively, maximizers’ preference for the best and their ability to spot new business opportunities may encourage them to pursue entrepreneurship. For these reasons, it is predicted that individuals who score high on maximizing will have greater entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 1: Individuals who score high on maximizing will have higher entrepreneurial intentions.

Innovation and Entrepreneurial Intentions

Individual innovation behavior at work has been referred to as “the intentional creation, introduction and application of new ideas within a work role, group or organization, in order to benefit role performance, the group, or the organization” (Janssen, 2000, p. 288). It is vital to the success of any business as new products, services, and processes allow organizations to achieve higher margins. Innovative individuals within the organization are key drivers of new developments that increase organizational performance (Shanker et al., 2017). These individuals tend to be more flexible and open-minded (Woodman et al., 1993; Yukl, 2009). They are encouraged by organizational factors such as fairness (Janssen, 2000), less restrictive environments (Shanker et al., 2017), and a climate that nurtures and encourages creativity (DiLiello & Houghton, 2006; Hunter et al., 2007). Employees who show innovative and creative potential are more likely to use their talents when they receive organizational support (DiLiello & Houghton, 2006). For example, leadership plays an important role in creating an environment that is conducive to innovation. Specifically, inspirational leaders create stimulating environments that motivate individuals to go beyond their typical work assignments (Bass & Avolio, 1994). Transformational leaders engage with followers’ personal value systems to increase their innovation behavior through intrinsic motivation (Janssen, 2000; Wilson-Evered et al., 2001).

Other studies have identified individual level variables that make employees more innovative on the job. Workers who are more confident across a wide range of work activities, have more autonomy, and express greater concern for their work report higher levels of innovation (Axtell et al., 2000). When employees view job stressors as challenges that lead to learning and growth, they are likely to use that mindset to innovate rather than be held back (Ren & Zhang, 2015). Training and development practices that increase employee’s knowledge, skills, and abilities have been found to benefit innovation in the nursing sector and among production employees (Knol & Van Linge, 2009; Pratoom & Savatsomboon, 2012). Other human resource incentives, such as better pay (Sanders & Lin, 2016), job security (Sanders & Lin, 2016), task composition (Dorenbosch et al., 2005), and autonomy (Bysted & Jespersen, 2014) similarly promote innovation on the job.

The innovation process requires questioning the status quo to identify potential improvements and new ways of doing business. There are generally two modalities of thinking styles used to solve problems: systematic and intuitive (Jabri, 1991). A systematic problem solver uses associative thinking patterns based on habits, routines, and adherence to specific rules and procedures. These individuals tend to follow set routines and stay within disciplinary boundaries to generate conventional solutions to problems. Intuitive thinkers tend to ignore conventional rules by processing information from disparate paradigms simultaneously to generate novel solutions to problems. Their ability to bring together information from different domains makes intuitive thinkers more innovative in the workplace as they are better at identifying new methods and solutions that may be found outside the normal range of alternatives (Scott & Bruce, 1994). Intuitive thinking involves searching for other possibilities that may exist in different domains and weighing the costs and benefits of various alternatives to find optimal solutions.

Maximizers utilize extensive alternative search as they attempt to find the best solution to problems (Schwartz et al., 2002). They prefer more options to less and perceive added utility from being able to weigh both positive and negative outcomes concurrently (Polman, 2010). These individuals enjoy meticulously scanning through as much information as possible before deciding on the best course of action. For example, consumers who maximize are more likely to purchase items that display more (vs. fewer) features because they perceive added utility from the additional choices (Brannon & Soltwisch, 2017). Maximizers are literally willing to go the extra mile to attain better selections. For example, one study found that maximizers are more willing than satisficers to drive long distances to ice cream parlors that have 200 flavors rather than 20 (Dar-Nimrod et al., 2009).

As entrepreneurs, those who maximize put forth greater effort to search their environment for new opportunities and threats, using that information to inform their strategy (Soltwisch, 2021). Having an entrepreneurial orientation allows them to gain knowledge in the areas of market information, customer relationships, and human capital in a way that enhances their marketing capabilities and performance (Martin & Javalgi, 2019). This awareness of their external environment opens opportunities to innovate and outmaneuver competitors, benefiting entrepreneurial performance in highly competitive (Martin & Javalgi, 2016) and technologically turbulent markets (Martin et al., 2020).

Not only are maximizers prepared to go to great lengths to find the best options for themselves, but they are also willing to put forth that effort for others and will advise them to also search for better options (Luan et al., 2018). Maximizers display more counterfactual thinking to produce multiple arguments to inform their decision-making (Leach & Patall, 2013). They are more future-oriented and aware of decision trade-offs (Misuraca et al., 2016). This role as a devil’s advocate may encourage them to explore the efficacy of new methods and techniques within their work teams. Maximizers have a clear idea of what their goals are and use tenacity and persistence to meticulously process large amounts of information to achieve them (Misuraca et al., 2015). Their high standards provide a continuous drive to find better solutions to problems (Schwartz et al., 2002). For these reasons, it is predicted that individuals who score high on maximizing will report being more innovative.

Hypothesis 2.a.: Individuals who score high on maximizing will report greater innovation behavior.

Innovation is an important part of the entrepreneurial process and an important antecedent to firm performance (Pitchayadol et al., 2018; Schenkel et al., 2019). Innovation is the ability of entrepreneurial individuals to recognize opportunities to produce new and practical ideas, introduce new products and services, and create new markets (Chen, 2007). Researchers persistently argue that entrepreneurs have higher levels of innovative attributes than their non-entrepreneurial counterparts. For example, Drucker (2014) proposes that innovation is a key facet of entrepreneurship and describes it as the systematic search for new opportunities created by changes in new products, ideas, or markets.

Since entrepreneurs must first identify opportunities before they can turn them into workable solutions (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), their ability to think creatively and search for improvements becomes instrumental to the entrepreneurial process. Individuals who can, and do, identify more opportunities would be more inclined towards exploiting those opportunities through entrepreneurial means. Studies have shown that innovativeness and innovation behavior is linked to greater entrepreneurial intentions (Gürol & Atsan, 2006; Syed et al., 2020). In a study comparing students in the U.S. and Turkey, innovation behavior was a significant predictor of entrepreneurial intentions regardless of cultural differences (Ozaralli & Rivenburgh, 2016). In line with this research, it is predicted that individuals who report more innovation behavior will have greater entrepreneurial intentions than those who report being less innovative.

Hypothesis 2.b.: Individuals who report more innovation behavior will have higher entrepreneurial intentions.

With the arguments and evidence presented in hypothesis 2.a. and hypothesis 2.b. in mind, we further suggest the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2.c.: The positive relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions is mediated by innovation behavior.

Entrepreneurial Alertness and Entrepreneurial Intentions

It is first necessary for entrepreneurs to recognize business opportunities before they can act on them (Rita et al., 2018; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Opportunities are often created by new technologies, market inefficiencies, or political, regulatory, and demographic changes (P. F. Drucker, 1985). Being alert allows individuals to identify these changes through the development of cognitive schema to process and organize information from multiple domains (Gaglio & Katz, 2001). Kirzner (1979) described entrepreneurial alertness as a distinctive set of cognitive processing abilities that allows individuals to identify opportunities that may be overlooked by others. Personal dispositions shape what individuals pay attention to in their environment (Shepherd et al., 2017). An individual’s background with specific knowledge domains – such as prior experience, specific information, or frustrating experiences with a product – makes the individual more alert to opportunities (Gaglio & Katz, 2001; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Tripsas, 2008). After recognizing an opportunity, entrepreneurs use information search to evaluate if the opportunity is viable (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006).

In general, maximizers spend more time and effort scanning their environment to find the best options (Schwartz et al., 2002). For example, in the career search process, maximizers searched for more opportunities and utilized more external information to land better jobs (Iyengar et al., 2006). In this process they evaluated both apparent and not-so-apparent opportunities to find superior positions. In another study, maximizers were more willing than satisficers to complete an extra survey if it gave them the chance to choose from a box of chocolates with 36 choices rather than 6 (Dar-Nimrod et al., 2009). Consumers who maximize are more likely to spend additional time searching for gifts (Chowdhury et al., 2009), and are more likely to purchase products that have additional features as they perceive added utility from the extra options (Brannon & Soltwisch, 2017). Maximizers’ extensive information search may allow them to see opportunities that others miss. Their extra effort to weigh alternatives (Chowdhury et al., 2009), consider larger option sets (Nenkov et al., 2008), and do more background research before making a choice (Iyengar et al., 2006; Nenkov et al., 2008) may help them evaluate the viability of opportunities they find.

Researchers have learned that a positive belief in one’s decision-making ability is a predictor of identifying entrepreneurial opportunities (Krueger & Dickson, 1994). Maximizers are more confident in their abilities to make decisions and enjoy the process (Lai, 2010), potentially encouraging them to look for openings where they can explore new ideas on their own terms. Because maximizers make more upward social comparisons and engage in counterfactual thinking (Schwartz et al., 2002), they may be more likely to search outside their organization to identify new and better business methods. The combination of their preference for more information, constant search for better alternatives, and belief in their decision-making competence may allow maximizers to identify more business opportunities. Therefore, it is predicted that individuals who score high on maximizing will have greater entrepreneurial alertness.

Hypothesis 3.a.: Individuals who score high on maximizing will have greater entrepreneurial alertness.

Entrepreneurial alertness is an important antecedent to entrepreneurial intentions. Research on entrepreneurs has found that they continuously scan their environment to identify new business opportunities (R. Hu et al., 2018). They also identify more potential opportunities than their non-entrepreneur counterparts (Cooper et al., 1988). Prior research has found that entrepreneurial alertness is positively related to entrepreneurial intentions (Dahalan et al., 2015; Van Gelderen et al., 2008). Interestingly, those who expressed positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship were more likely to be alert to new business ideas, and subsequently had higher entrepreneurial intentions (Dahalan et al., 2015). Thus, entrepreneurial alertness is a mediating variable that allows individuals who may be inclined toward entrepreneurship to recognize and pursue business opportunities. Similarly, others have found that entrepreneurial alertness mediates the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurial intentions (R. Hu et al., 2018). In line with this research, it is predicted that individuals who are entrepreneurially alert will have higher entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 3.b.: Individuals with greater entrepreneurial alertness will have higher entrepreneurial intentions.

With the arguments and evidence presented in hypothesis 3.a. and hypothesis 3.b. in mind, we further suggest the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3.c.: The positive relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions is mediated by entrepreneurial alertness.

Entrepreneurship is a dynamic process in which entrepreneurs make various decisions (Alvarez et al., 2013; Grégoire & Shepherd, 2012). Opportunity evaluation, and more specifically estimating the attractiveness of an opportunity, is an important phase of this process. In this phase, entrepreneurs make decisions about the personal attractiveness of investing resources toward introducing something new to the market (Williams & Wood, 2015). Scholars have developed a synthesized model of opportunity evaluation which introduces opportunity attractiveness as a multi-dimensional formative construct including gain estimation, loss estimation, perceived desirability, and perceived feasibility (Scheaf et al., 2020). This construct is used to further evaluate the relationship between maximizing and entrepreneurial intentions to see if maximizers evaluate business opportunities more favorably. Because maximizers set higher goals for themselves and will sacrifice time and effort to achieve a more desirable future, they may perceive opportunities as being more attractive (Misuraca et al., 2016). They are also more likely to see goals as being within their reach (Luan & Li, 2017). Therefore, it is predicted that opportunity attractiveness will mediate the relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions.

Hypothesis 4: The positive relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions is mediated by opportunity attractiveness.

Study 1

Procedure and Measures

Two hundred and fifty-eight participants from the United States were recruited for the study using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT). Five participants were removed due to incomplete data, leaving a final usable sample of 253 participants. Participants responded to a questionnaire measuring the focal variables in the study along with demographic information (32% female, mean age = 33, with an average of 10 years work experience). All industry divisions of the Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system were represented in the sample, with services, manufacturing, and public administration representing the largest percentages at 25%, 17%, and 15% respectively. Prior to launch, the survey was pilot tested with faculty members, graduate students, and colleagues to ensure accuracy and clarity. Linan and Chen’s (2009) six-item entrepreneurial intentions scale was used to measure the dependent variable (Cronbach’s α = .91). Participants were asked to rate the statements on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 7 = totally agree). Some examples of the entrepreneurial intentions scale items include: “A career as an entrepreneur is attractive for me”; and “Among various options, I would rather be an entrepreneur”. This scale has been used to measure entrepreneurial intentions in previous studies (Hsu et al., 2019; Lee-Ross, 2017; Liñán & Chen, 2009).

The underlying process of innovation behavior was measured with a 6-item Innovation Performance Scale (M.-L. M. Hu et al., 2009; Cronbach’s α = .86). Items range on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors of (1 = totally disagree; 7 = totally agree). Examples of items for the scale include: “At work I seek new techniques and methods”; “At work I sometimes propose my creative ideas and try to convince others”; and “At work I provide a suitable plan and workable process for developing new ideas”. The other mediating variable (entrepreneurial alertness) was measured using the 13-item entrepreneurial alertness scale designed to capture the three dimensions of scanning & search, association & connection, and evaluation & judgment (Tang et al., 2012; Cronbach’s α = .89). Example items include: “I always keep an eye out for new business ideas when looking for information”; I see links between seemingly unrelated pieces of information"; and “I have a knack for telling high-value opportunities apart from low-value ones”. Finally, to measure the independent variable (maximizing or satisficing), participants completed the nine-item Maximizing Tendency Scale (MTS; Highhouse et al., 2008; Cronbach’s α = .79) at the end of the survey. Some examples of the Maximizing Tendency Scale items include: “I am a maximizer”; “My decisions are well thought through”; and “I never settle”.

Analysis and Results

To recap the predictions, it was posited that maximizers would show greater entrepreneurial intentions. Underlying this process, it was proposed that maximizers would report themselves as being more innovative and alert to opportunities. To test this, entrepreneurial intention scores were regressed on participants’ maximization scores. Consistent with the predictions of hypothesis 1, results indicate that there is a significant positive relationship between maximization scores and entrepreneurial intentions (b = .48, t(251) = 7.73, p < .01). This coefficient remained significant when the demographic controls of age, gender, and years of experience were included (See Table 1 for correlations, Table 2 for regression results, and Table 3 for reliabilities).

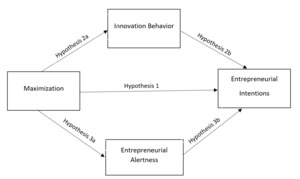

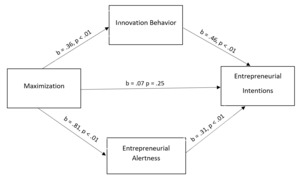

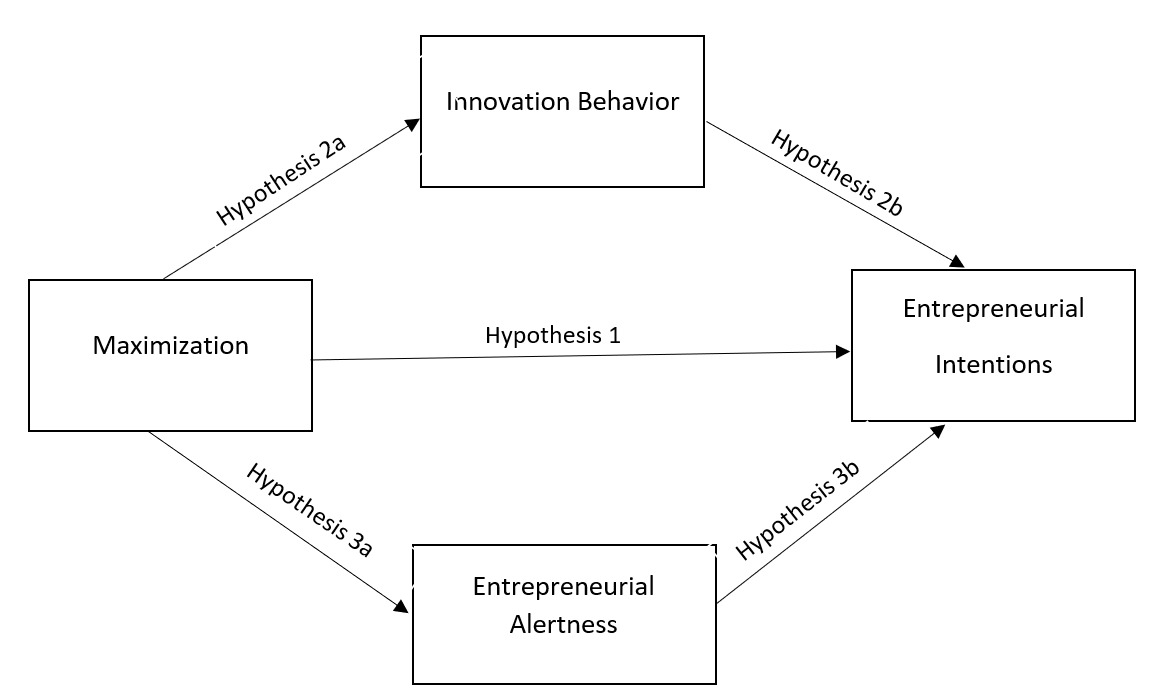

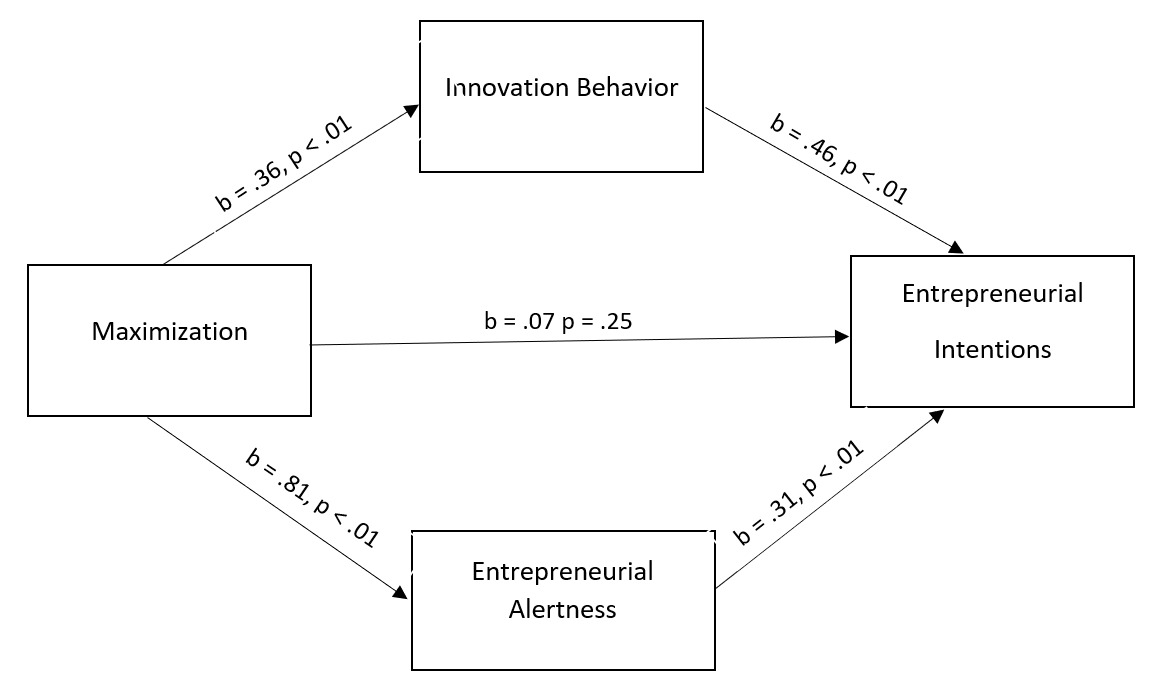

Hypotheses 2.a. and 2.b. proposed that maximizers would show higher innovation behavior, and that those who are more innovative would have greater entrepreneurial intentions. Taking these together, hypothesis 2.c. suggests that innovation behavior may mediate the relationship between maximization and entrepreneurial intentions. Hypotheses 3.a., 3.b., and 3.c. together suggest that entrepreneurial alertness may also mediate the path between maximization and entrepreneurial intentions. Parallel mediation was tested using model 4 of the bootstrapping process described by Hayes (2017) with 5,000 samples. The controls of age, gender, and years of experience were included as covariates in the model. Results of parallel mediation are shown in figure 2 below.

The first leg of the first path indicated that maximization was significantly related to innovation behavior (b = .36, t(251) = 8.29, p < .01). The second leg of the first path found that innovation behavior was significantly related to entrepreneurial intentions (b = .46, t(251) = 4.74, p < .01). Thus, consistent with the predictions of hypotheses 2.a., 2.b., and 2.c., innovation behavior mediated the positive effect of maximizing on entrepreneurial intentions (b = .16, CI95% exclusive of 0 [.06, .29]). The first leg of the second path of the entrepreneurial alertness mediation indicated that maximization was significantly related to entrepreneurial alertness (b = .81, t(251) = 11.36, p < .01). The second leg of the second path between entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial intentions was also significant (b = .31, t(251) = 5.05, p < .01). Thus, consistent with the predictions of hypotheses 3.a., 3.b.,and 3.c., entrepreneurial alertness mediated the relationship between maximization and entrepreneurial intentions (b = .24, CI95% exclusive of 0 [.11, .40]). The total effect of the parallel mediation was b = .48, t(251) = 7.73, p < .01. The direct effect was b = .07, t(251) = 1.14, p =.25), confirming parallel mediation.

The first study identified that decision making styles play an important role in how individuals respond to entrepreneurial opportunities. It was found that individuals who maximize have greater entrepreneurial intentions. Underlying this effect, the data suggests that maximizers are more innovative and alert to opportunities in their environment. Therefore, it appears that the parallel processes of recognizing opportunities and innovation behavior are important to how maximizers may pursue entrepreneurial endeavors.

In order to further explore the process of identifying opportunities to pursue, we conducted a second study to investigate hypothesis 4 which states that opportunity attractiveness will mediate the relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions. The second study expands on the first study in several ways. First, it investigates how maximizers evaluate a specific opportunity to identify what aspects of the opportunity are most likely to increase their entrepreneurial intentions. Second, it enhances the validity of the first study by replicating the main effects of study 1 in a different sample.

Study 2

Procedure and Measures

A student sample was used in the second study. An online survey was sent to business students at a public university in the United States. Extra points were provided to the students who participated in the study. There were 192 students who participated in the study. Among them, 175 students provided valid data (49% female, mean age = 20.4). The dependent variable (entrepreneurial intentions) and independent variable (maximization score) in study 2 are the same as study 1. A new mediator, opportunity attractiveness, was introduced to examine differences in how individuals evaluate a specific business opportunity.

The measurement of opportunity attractiveness is an important topic in entrepreneurship research. Recently, Scheaf and colleagues developed “an empirically validated scale that measures opportunity evaluation as a multi-dimensional model” (2020, p. 2). This measurement operates various methodologies, populations, and opportunity manipulations. It has an overall measurement, opportunity attractiveness, which has three essential elements: gain estimation, loss estimation, and perceived feasibility. The participants were provided with an opportunity and answered questions about their evaluations of the opportunity. The measurement includes 14 questions with a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 6 = Strongly Agree). The gain estimation measurement has six items. For example, “I see large potential gains for myself in pursuing the opportunity”. The perceived feasibility measurement has four items. For example, “I have what it takes to create the opportunity”. The loss estimation measurement has four items. For example, “For me, the potential for loss in pursuing the opportunity is high”. Detailed measurements are included in the Appendix. Table 3 and 4 show the measurements, reliabilities, and correlations.

Analysis and Results

Mediation analysis was run using an SPSS macro, PROCESS v3.5 (model 4), using 5,000 bootstrapped samples for bias correction and to establish 95% confidence intervals (A. F. Hayes, 2017).

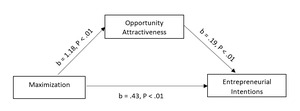

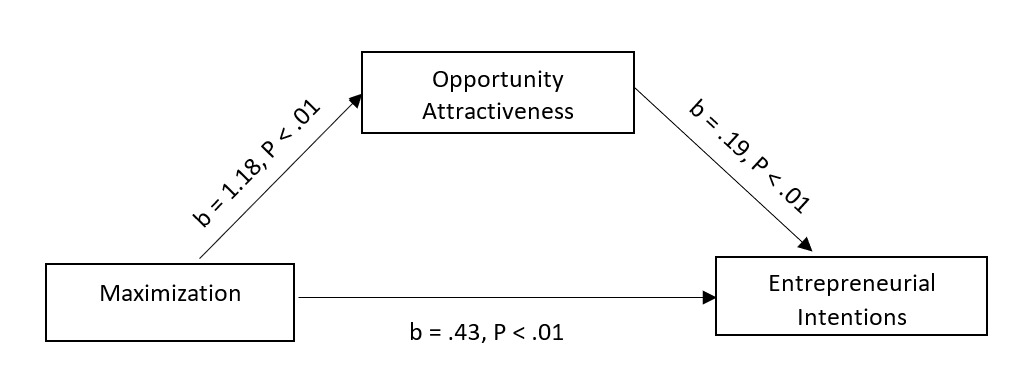

The mediation effect of opportunity attractiveness (OA), on the relationship between maximization score (MS) and entrepreneurial intentions (EI) as predicted by hypothesis 4 was tested. To test the first leg of the mediation model, MS was regressed on OA (b = 1.18, t(175) = 4.15, p < .01), indicating a significant relationship between MS and OA. The second leg of the mediation model was tested by regressing OA on EI (b = .19, t(175) = 5.01, p < .01). The total effect was b = .65, t(175) = 4.36, p < .01. The direct effect was b = .43, t(175) = 2.93, p < .01). The indirect effect was (b = .22, [.10, .37]). Thus, consistent with the prediction of hypothesis 4, the results confirmed the mediation effect.

The results indicate that, consistent with study 1, there is a significant positive relationship between maximization score and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, the participants’ opportunity attractiveness score mediated the relationship between maximization score and entrepreneurial intentions.

Discussion

In this paper, we hypothesized and tested the direct relationship between individuals with high maximization scores and their entrepreneurial intentions. We also hypothesized and tested three mediation hypotheses where the relationship between maximization and entrepreneurial intentions was mediated by innovation behavior, entrepreneurial alertness, and opportunity attractiveness respectively. The results indicate support for the proposed hypotheses, suggesting implications for entrepreneurship research and practice.

First, this paper contributes by identifying that decision-making styles (i.e., maximizing) may be an important antecedent to entrepreneurial intentions and thus advances our understanding of what drives individuals to become entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship plays an important role in economic development in our complex and dynamic business environment (Gyimah & Lussier, 2021; Śledzik, 2013). It was found that those who maximize reported greater entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurs continuously scan their environmental surroundings to identify business opportunities (R. Hu et al., 2018). Because the entrepreneurial mindset involves extensive search for opportunities, it is likely that maximizers fit into this role comfortably as they prefer to evaluate as many options as possible (Schwartz et al., 2002).

From a psychological standpoint it is reasonable that maximizers fit the entrepreneurial mindset. For example, maximizers’ higher intrinsic motivation, disposition for greater workloads, and self-efficacy likely plays a role in their pursuit of business opportunities. Maximizers find decision making activities enjoyable and feel more competent in their abilities (Lai, 2010), which may encourage them to explore new ideas on their own terms. Maximizing has also been linked to various leadership traits. For example, executives who maximize report putting in more work to obtain the best possible outcomes (Lai, 2010). Maximizing has been linked to greater managerial effectiveness as managers who seek out the best utilize decision making skills and emotional intelligence to interact with others more effectively (Soltwisch & Krahnke, 2017). It is possible that maximizers are more inclined to pursue entrepreneurship because they believe in their ability to lead a new venture through the start-up process.

A theoretical implication of this finding is that the decision-making competencies associated with maximizing might partly explain the important role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy both in choosing entrepreneurship as a career option and in the success of entrepreneurial firms. A practical implication of this finding is that the tendency to maximize could be tested in the application process of organizations that aid in entrepreneurship (e.g., business incubators) as well as in the hiring process of established firms that want to hire entrepreneurial business leaders. Hiring individuals who are maximizers might enhance the success of such programs and enhance person-employee fit in cases of established firm hires. Future research could follow-up on this to investigate the relationship between maximizing and entrepreneurial self-efficacy.

Second, this paper contributes by improving our understanding of what drives innovative behavior in the workplace. Trying out new or improved products, services, or ways of doing things is critical to all aspects of economic activity (Fagerberg et al., 2010). The way that individuals gather information when making decisions appears to be an important factor in innovation behavior. Specifically, those who seek out as much information as possible to find the “best” choice (maximizers) report greater innovation behavior than those who satisfice. Cognitive schemas shape how we interpret information in our environments. It appears that those who continuously seek out as much information as possible to find optimal solutions may be more likely to identify and implement new and improved products, services, and business methods in the workplace. A theoretical implication of this finding is that connecting the dots has been considered an important skill in entrepreneurship and maximizers’ innovative ability and their usually thorough search and analysis strategy might provide the rationale for why some individuals are better at connecting the dots. A practical implication of this finding is that human resource professionals may find it useful to test for maximization tendencies to identify individuals who are a good fit for innovative positions.

Further research could explore how maximizing and satisficing decision-making styles interact together in the workplace to foster innovation. It is likely that these styles are complementary in the innovation process. Conceivably, a team of all maximizers may spend too long exploring every possible innovation at the expense of not actually moving forward on any specific product. In one study involving an escape room game where participants must solve puzzles in a certain amount of time to win, or escape the room, teams with higher mean maximization scores only performed better when they cooperated (Schei et al., 2020). Interestingly, teams with just one maximizer also benefited by generating more alternatives through cooperation. Conceivably, it is possible that having too many maximizers on the team generating alternatives and attempting to control the decision process could cause analysis paralysis, leading to a lack of cooperation. Having at least one satisficer in the group would likely be beneficial as they may encourage the team to move forward with viable alternatives even though they may not be the absolute best. The complementary nature of these decision-making styles could be further explored to understand the best composition of innovative work teams.

Third, this paper contributes by providing evidence that maximizers may have higher entrepreneurial alertness, leading to higher entrepreneurial intentions. Being alert to opportunities has been recognized as an important aspect of the entrepreneurial process (Tang et al., 2012). It is likely that the parallel processes of innovation and entrepreneurial alertness work together as they allow entrepreneurs to experiment with new methods that they observe in their competitive landscape. Information search, both within and outside the business, may allow for the adoption of new business methods and techniques that create a competitive advantage. A theoretical implication of this finding is that opportunity recognition is explained by the thoroughness in decision-making that characterizes an entrepreneur or a potential entrepreneur, but this same characteristic may potentially inhibit opportunity exploitation which requires quick action. A practical implication of this finding is that if a potential entrepreneur at an early stage of the entrepreneurial process is looking for a co-founder, then it would be helpful to test potential co-founders for their maximization scores and partner with those who have high scores. Further research could explore the interactive effect of innovation behavior and entrepreneurial alertness in the relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions.

Finally, as seen in the results of our second study, this paper further contributes by showing that maximizers tend to see opportunities as being more attractive overall. McMullen and Shepherd’s (2006) model of entrepreneurial action posits that entrepreneurs are more likely to see opportunities as being viable as they move from the attention stage to the evaluation stage. It is the evaluation stage that allows them to assess if the opportunity is feasible and desirable. Maximizers’ favorable view of the opportunity may be due to their constant quest for better options (Schwartz et al., 2002) and confidence in their ability to make decisions (Jain et al., 2013).

Similar to other studies finding that maximizers search for more job opportunities (Iyengar et al., 2006), maximizers may be more likely to seek out entrepreneurship as an alternative way to fulfill their career goals. It appears that maximizers are more likely to view business prospects as attractive opportunities. Previous research on maximizing and satisficing has recognized that maximizers seek out more options to find the best; however, this study identifies that they may also see those options as being within their reach, leading to a greater propensity to follow through on them. This optimism could be based on their confidence in their ability to make subsequent decisions that would assist them in achieving their goals. A theoretical implication of this finding is that maximizers’ favorable view of opportunities might partly explain optimism bias which has been previously found in entrepreneurs (Elhem et al., 2015).

This study extends previous work connecting innovation to entrepreneurial intentions (Gürol & Atsan, 2006; Ozaralli & Rivenburgh, 2016) by identifying that fundamental differences in decision making styles may be an impetus for turning new ideas into business opportunities. A practical implication of this finding is that those who are driven to find the best may be more likely to champion new product or service innovations. Whether this is done through corporate entrepreneurship or by starting a business, these individuals are likely central to the process of bringing new products and services to market. Future research could investigate boundary conditions for this effect by identifying what circumstances encourage maximizers to identify and champion new ideas. As business leaders continue to develop new products and services in competitive environments, this study provides a first look at how maximizing or satisficing decision-making styles influence innovation and entrepreneurship.

Limitations

Although this paper makes multiple contributions that have important implications and future research potential as described in the discussion section above, this paper also has some limitations. The first limitation of the paper is that it partly uses student respondents (i.e., in study 2). Student respondents can be an appropriate sample for entrepreneurial intentions research as they are at a career search and decision stage, yet it will enhance the generalizability of our findings if future researchers test the model in study 2 using general population respondents. A second limitation of our paper is that our respondents are all based in the United States, as is true for a lot of the published entrepreneurship research. Although a very important part of the global economy, the United States accounts for only about 4% of the global population. Therefore, we suggest that future researchers test our models using a global sample similar to the great work being done by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (G.E.M.) researchers. Finally, a third limitation of our paper is that, given the exploratory nature of the research, respondents completed all measures in a single survey. Even though survey data is used in many entrepreneurial studies, interesting variations, if any, in the tested models might be found if data is collected at multiple time periods using mixed methodologies. Replicating the main results in study 2 enhances generalizability, however, it would be interesting for future researchers to study longitudinal effects by following up with maximizers to better understand how they approach entrepreneurial decisions over time. This will allow future researchers to test the robustness of our models and to find any variations that might occur with different types of decisions.

Conclusion

Building upon existing literature, in this paper we hypothesized that individuals high on maximization (i.e., maximizers) will have higher entrepreneurial intentions. We further hypothesized that this direct relationship is mediated by innovation behavior, entrepreneurial alertness, and opportunity attractiveness. Utilizing two studies, one with 253 U.S. working professionals and another with 192 students, support was found for the proposed relationships. Thus, our results suggest that maximizers have higher entrepreneurial intentions, and this relationship is mediated by their innovation behavior and entrepreneurial alertness. Further, our results also suggest that maximizers find business opportunities more attractive, leading to a greater propensity to follow-through with them. This paper explores the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between maximizers and entrepreneurial intentions. Undoubtedly, future research can build on these findings to further our understanding of what drives this important business process.