Introduction

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are entrepreneurial entities that constitute the cornerstone of emerging economies (Chege & Wang, 2020; Jabbouri & Farooq, 2020). SMEs make a substantial contribution to a country’s economic growth, and their performances also reflect the effectiveness of public policies in cultivating an innovative mindset in an economy. Like most other emerging economies, Pakistan’s economic system largely depends on SMEs, which account for more than 99 percent of the overall enterprises. Manufacturing is the second dominant industry of the domestic economy behind agriculture, accounting for 27 percent of Pakistan’s GDP in 2020-2021 (STATISTICS, 2021), rendering it the most key strategic activity of business. Prior research suggests that SMEs’ incapability to utilize the resources adequately has worsened their vulnerability in both advanced and emerging economies (Khan, 2015). Such phenomena are of vital significance not just to executives and government bodies but to academia as well.

Despite their growing importance to the economic development and entrepreneurs, SMEs face challenges in accessing funds, experience, and R&D. Previous literature reveals that the primary amount of financial invested capital is highly positively associated with firm performance and growth (Cooper et al., 1994; O’Neill & Duker, 1986). Greater financial capital serves to protect against slow start-ups, industry downturns, or inadequate decision-making. Firms with financial constraints are frequently the contributing factor to firm breakdown and depart from the industry (Crook et al., 2011; Rujoub et al., 1995; Shaw et al., 2009). Similarly, previous experience in the firm is beneficial in developing capabilities that are pertinent for its successful planning and innovation. When an organization has prior experience with joint ventures, it can address the questions of how to deal with other competitors in the industry (Barkema et al., 1997; Park, 2011). The risk rate for inexperienced firms is higher than for experienced firms initially (Fritsch, 2013), but we foresee that the entrepreneur has previous experience in the same industry to be beneficial to the firm’s performance and sustainability. Multinational firms learn from experience they acquire from the host country’s innovative culture (Figueira-de-Lemos et al., 2011; Vahlne & Nordström, 1993). Moving ahead, (Kotabe et al., 2002) argued that research and development (R&D) could be a crucial component that contributes to firm survival, performance, and growth. Numerous prior literature (Artz et al., 2010; Mansfield, 1981; Revilla & Fernández, 2012) have also discovered a positive relationship between R&D intensity and firm progression.

Technology, like other resources, is ubiquitous in the formation of new enterprises seeing as technology facilitates corporations in converting external inputs such as new knowledge into innovative organizational competencies that eventually contribute to firm growth (Melville et al., 2004), enhanced innovation, and economic performance (Benner & Veloso, 2008). Conversely, for developing economies, technology creates parallel commitment. Still, it contains several challenges, including a prevalent insufficient funding, hitches in accumulating basic operating systems, lack of R&D intensity, transportation problems, high unemployment, lack of exposure to ICT networks, and poor educational systems to offer general knowledge and skills, which all generate greater impediments to strengthening competences to support innovation for their enterprises (Neumeyer et al., 2020). Under such circumstances, The existence of cultural homogeneity identifies a set of “clusters” and the concept that they can assist in flourishing in the market structure, contributing to sustained economic development in several emerging economies (Callegati & Grandi, 2005). The innovation culture generates a setup in which organization members can seek new opportunities to develop and enforce innovative business models to increase profitability (Halim et al., 2015). The intensity with which opportunities to communicate change in business products and processes are explored in an innovation culture. Although capital investment, experience, and R&D intensity all positively contribute to firm performance in large corporations, it would be fascinating to study these relationships in SMEs, particularly in environments with a high level of creativity, such as an innovation culture.

To overcome the identified gaps, we initially perform a comprehensive literature review, looking at traditional frameworks of how entrepreneurs implement innovation culture in their firms and the challenges they encounter. Following that, we propose a conceptual framework offering a distinct approach to innovation culture and its indirect impact on enterprise economic performance. The purpose of this study is to investigate how initial capital investment, entrepreneurs’ experience, R&D intensity, and innovation culture affect the SMEs’ performance. Further, innovation culture moderates the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables. Although several previous studies explicate that large initial capital investment, previous experience, and R&D intensity affect firm survival and performance positively (Artz et al., 2010; Cooper et al., 1994; Park, 2011), and international firm achieves innovation and efficiency through seeking and implementing knowledge, information, and R&D in improving performance (Aksoy, 2017), more concentration is given mostly to multinational firms and its subsidiaries, and very less concentration is given to domestic or small size SME in this regard. Our study will contribute to the existing literature by investigating our research questions using a sample data collected from 337 respondents of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) from Pakistan and analyzed by applying SPSS 23.

Literature Background and Hypothesis

Importance of Innovation Culture in SMEs

Innovation is considered as a divergence from existing management concepts, methods, and techniques or a shift beyond conventional business models that determine the way a corporation operates (Kahn, 2018). Innovation is described as a firm’s acceptance of a novel concept or behavior that could be of new products, services, or technologies (Dziallas & Blind, 2019). Similarly, adaptability to be innovative is a mechanism of converting potentials into pragmatic value (Keskin et al., 2020), and it develops once implemented (Sharifirad & Ataei, 2012). Organizations that are capable of innovating can receive greater input from their surroundings, as well as greater exposure to the competencies required to enhance firm performance to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Value creation through innovation is a clearly strategic advantage (G. Santos et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, several firms may perform better and be positioned higher than competitors to capitalize on the available opportunities. Considering this, SMEs would face a significant drawback in comparison to many large-size competitors. The latter may always have higher economic capability, extensive talents, better accessibility to manufacturing and distribution assets, and would be best suited to protect copyrights (Müller et al., 2021). Nonetheless, bigger does not mean perfect necessarily and SMEs should not signify doomed, considering innovation usually applies to a segment instead of the overall product (Leckel et al., 2020). To generate creative solutions, SMEs may be competent in specialized fields. For example, SMEs can achieve competitive advantage by being adaptable to capitalize on modern technologies; collaborating with strategic associations that contribute to the knowledge improvement and financial arrangements required to acquire major technological capabilities; and being proactive and prematurely to recognize vogue in modern contingencies (Keskin et al., 2020).

To attain innovation, SMEs should have common values and comprehension (Dziallas & Blind, 2019), where processes of innovation emerge inside a specified socio-economic scenario and the nation’s socio-political traditions (Tian et al., 2018). Several studies have proven the interaction between firm innovativeness and firm age, size, and structure (Petruzzelli et al., 2018); culture, size, and gender (S. C. Santos & Neumeyer, 2022); smart decision-making (Bokhari & Myeong, 2022); the organizational relationships (Agostini & Nosella, 2019); innovation performance relationship with organizational learning and market orientation (Abdul-Halim et al., 2019); and consumer and market positioning (Keskin et al., 2020). Considering the obstacles and complexities of innovation, a cultural approach may be adequate in comprehending innovation (Hanifah et al., 2019; McCausland & McCausland, 2022). From this perspective, entrepreneurial enterprises, especially SMEs, must promote “a culture of pride and a climate of success” (Baregheh et al., 2012; Ripolles Meliá et al., 2010). Culture is one of the critical components of innovation management (Pohlmann et al., 2005). That is due to comprehending the principles that govern and support the organizational culture is critical to success in any corporate environment.

Innovation culture is essential because it enhances cohesiveness and devotion and develops certain concrete norms for attitudes and adequate behaviour (Arsawan et al., 2020; Dabić et al., 2018). In that perspective, SMEs figure prominently in promoting an environment that fosters a firm’s innovation and economic performance. Innovation culture can be divided into four groups such as innovation intentions, resources to accommodate innovation, actions to impact business alignment and personal value, and the atmosphere to deploy innovation (Dabić et al., 2018). In such context, innovation culture is considered to be multifaceted; nonetheless, in SMEs context, whose nature is brittle and compact, innovation culture is presumed to be peripheral to embracing the systemic approach to innovation culture wherein interaction and connection are improved and versatile formation, encouraging workforce, taking risks, alignment, acquiring knowledge, and expertise are appreciated (Hanifah et al., 2019). Though SMEs get a significant innovation culture (Arsawan et al., 2020; Ghasemzadeh et al., 2019), the concerns about innovation culture in emerging nations are growing rapidly (Hanifah et al., 2019), specifically in Pakistan (Khattak, 2022).

Further, there appeared to be a dearth of experimentally documented advantages in Pakistani SMEs implementing an innovation culture (Khattak et al., 2021). Because the Pakistani industry considers innovation culture as new, it is of significant relevance to examine such a crucial issue from the perspective of SMEs (Halim et al., 2015). Even so, it will be quite fascinating to delve deeper into the implementation of innovation culture amongst Pakistani SMEs.

Initial Capital Investment and SME Performance

Initial capital investment is considered a backbone when a new SME enters the industry. The initial investment may provide subsistence for the new entrant firm against the liabilities of newness and smallness. The availability of financial capital to make extensive financial strategies and R&D that cannot be imitated by competitors can have an impact on firm performance (Chandler & Hanks, 1998; Linder et al., 2020). Initial capital invested in a business has a positive influence on the firm survival and economic growth (Désiage et al., 2010; O’Neill & Duker, 1986). The amount of capital is also affiliated with the entrepreneur’s immediate financial strategies to pursue the firm’s objective of survival and growth. A small retailer, for instance, with enormous economic means, can initiate a business with a large variety of diverse products in its product line (Ganesan et al., 2006). A large initial financial capital assists the SME in understanding the market and overcoming the complications encountered in the industry over time (Cooper et al., 1994). (Cooper et al., 1992) asserted that six out of eight studies discovered a significant positive relationship between larger initial capital and higher firm performance. Hence, we develop our hypothesis as:

Hypothesis 1: Larger the initial capital investment of a new entrant SME, the higher the likelihood of viability and economic performance

Prior Experience and SME Performance

Previous research found that product attributes expertise was a determinant of technology adoption, lending substance to the premise that entrepreneurs who make an immense effort to comprehend emerging innovations are more willing to implement them (Peltier et al., 2012). Since new entrants must use some technologies to survive while being inexperienced, they encounter obstacles in the early stages because they are blissfully ignorant of market momentum, routines of work and administration procedures, and legitimacy with vendors and clients (Çalişkan, 2010; Cooper et al., 1994; Mubarik, 2015). This phase of technological exploration is extremely crucial and difficult for the firm’s survival because test repetitions and failures characterize it. The previous experience and managerial competencies of the firm’s entrepreneur are essential for its survival in this modern digital age (Neumeyer & Liu, 2021). An experienced founder can discover better opportunities to obtain the necessary capital (Timmons, 1989), but certain firms do not need a capital structure because they can always find financing thanks to their prior experience with multiple good projects (Macpherson & Holt, 2007). The founder of a new SME gains experience from his previous organization where he worked as general manager, years of work expertise running his own some other related business, years operational with technical or any specialized area, and his education in the related field (Chandler & Hanks, 1998; Geroski et al., 2010). A founder with extensive experience is more likely to make his SME survive and grow successfully. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Higher the prior experience a new entrant SME founder has, the higher the likelihood of viability and economic performance

R&D and SME Performance

Previous literature suggests that innovation and creation have an impact on SME economic performance as well as increase economic growth (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1986). When an SME makes higher investments in R&D before entering in industry, it gains a competitive advantage. (Schumpeter, 2010) contends that SMEs invest more in R&D and earn higher returns in the early stages, achieve competitive advantage from inimitable R&D, charge monopoly and oligopoly revenues, survive in the industry always, and get higher economic benefits. Besides, (Mukhopadhyay, 1985) suggests that the entry barrier can be reduced through quick imitation, and a new firm can survive if it can imitate the R&D of other successful firms. The advent of modern technology adoption reduces production costs and enhances SME economic growth, which has a significantly positive effect on its survivability (Neumeyer et al., 2020).

Further, It is argued that firms indulge in R&D to minimize costs to prevent competitive price pressure. This could also offer an opportunity for a firm to reinforce its technologies to flourish in a volatile market (Cellini & Lambertini, 2009). Firm size is predicted to be impacted by the effect of R&D activities (Klepper & Simons, 1997), and it varies across industry sectors. When compared to smaller ventures, larger firms are superior in capitalizing on the benefits of R&D investment, and higher technology firms focus primarily on R&D activities than lower technology firms in the industry (Artz et al., 2010; Sampson, 2007). Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: Higher the R&D intensity of new entrant SME, higher the likelihood of viability and economic performance

Moderating Role of Innovation Culture

Findings from previous literature suggest a significant relationship between culture and performance (Kotter, 2008; Sackmann, 2011; Shahzad et al., 2012). In a dynamic digital corporate environment, digital innovation is a vital prerequisite for competitiveness and economic growth regardless of its size or industry (Franco et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018); nevertheless, it is complicated to implement digitalization without a culture that stimulates the enterprise to flourish especially more significant in SMEs (Halim et al., 2015). Corporations foster innovation by utilizing digital technologies to transform their business structure in an attempt to acquire expertise across the entire organization (Valencia et al., 2010). Consequently, members of the organization share values, ideologies, and attitudes in a way that promotes an innovative culture (Ali & Park, 2016). This facilitates economic growth and the acquisition of new knowledge, which enhances SME performance (Škerlavaj et al., 2007).

Prior research has explored the critical importance of an innovative culture in SMEs’ innovative performance (Halim et al., 2015). Immensely entrepreneurial interests and low endurance to change characterize a flexible, innovative culture (Saleh & Wang, 1993). An innovation culture enables a firm to generate novel methods for building new channels while integrating new techniques for marketing a valuable product to consumers (Gupta et al., 1986). The literature establishes a strong link between innovation culture and firm performance (Gupta & Gupta, 2019; Kotter, 2008; Sackmann, 2011; Shahzad et al., 2012; Uzkurt et al., 2013). Consequently, one might say that SMEs use innovation more effectively in an innovative cultural context to enhance SME profitability since culture is an important factor that impacts performance (Bokhari & Aftab, 2022; Kotter, 2008; Sackmann, 2011). It is assumed that there will be a significantly positive correlation between innovative culture and SME performance; thus

Hypothesis 4: Higher the innovation culture of a new entrant SME, the higher the likelihood of economic performances

Whereas earlier hypotheses demonstrated a fundamental relationship between innovation culture and economic performance, a better comprehension of this complicated relationship might provide insights into these phenomena. Innovating digitally means “innovating products, processes, or business models using digital technology platforms as a means or end within and across organizations” (Ciriello et al., 2018). The advancement of digital technologies has led to a significant systemic shift in the global economic system (Franco et al., 2021). Digitalization offers opportunities to improve features to the enterprise’s activities pertaining to the utilization of digital capability, the development of a system of digital value, and the consumer’s digital experience (Eller et al., 2020). This is a technologically driven transformation at multiple scales of the enterprise, involving equally the use of digital technologies to enhance current systems and the use of digital innovation that has the capacity to overhaul the business strategy (Ciriello et al., 2018). Digital innovation has such a significant impact on organizational performance (Zaefarian et al., 2017).

Previous literature revealed that initial capital investment has a positive impact on firm performance and growth (Cooper et al., 1994; Désiage et al., 2010; O’Neill & Duker, 1986), firm survival, economic performance, and growth are influenced significantly by entrepreneurs’ prior experience gained from the industry (Geroski et al., 2010; Macpherson & Holt, 2007), and higher R&D in the firm has a substantial impact on its economic survival and performance (Artz et al., 2010; Cellini & Lambertini, 2009; Hölzl, 2009). There are inconsistent findings between initial capital investment, prior experience of the entrepreneur, R&D, and firm performance, and an additional contextual variable that moderates the correlation between these variables is required. Several previous researchers have investigated the moderating role of innovation culture between knowledge assets and product innovation (Martín-de Castro et al., 2013), organizational learning and innovation performance (Ghasemzadeh et al., 2019), and the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance (Khan et al., 2019). We believe that innovation culture is the most suited variable to be adopted as a moderating variable in this study which means that the organization’s culture is dynamic, innovative, ambitious, exciting, stimulating, exploratory, result-oriented, and compressed. Hence, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 5: Innovation culture moderates the relationship between initial capital investment and SME economic performance positively

Hypothesis 6: Innovation culture moderates the relationship between the prior experience of entrepreneur and SME economic performance significantly

Hypothesis 7: Innovation culture moderates the relationship between Research & Development and SME economic performance substantially

Research Methodology

Data Sampling

An online survey was administered via e-mail to registered members of the Chamber of Commerce in Lahore, Faisalabad, and Karachi to collect data. The sample includes SMEs’ entrepreneurs, senior executives, and marketing and R&D directors, all of whom were responsible for the company’s adoption of innovative initiatives. Personnel from 1641 SMEs were requested to respond to the questionnaire, and 337 respondents finished the complete survey, yielding a response rate of 20.53%.

There are numerous sufficient grounds to concentrate on small and medium-sized firms. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) play a critical part in economic progress and income growth worldwide. Moreover, SMEs promote job creation, resulting in the most challenging environment in emerging nations (Bokhari et al., 2021; Saleh & Wang, 1993). Ultimately, innovative activities provide SMEs with the skills they require to reduce product life cycles, boost survival rates, and compete and expand in a challenging environment (Rosenbusch et al., 2011). This is particularly important for small businesses in developing countries with limited resources, as innovation is an expensive process (Vrgovic et al., 2012). Table 1 provides summary statistics for our data collected for the overall sample.

Measurement Instruments

Prior experience, R&D, and innovation culture were all measured using multi-item scales. A 5-point Likert-scale (between 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree) was utilized to determine participants’ intensity of agreement with the opinion. An online survey questionnaire was adapted from previous research and adapted to the study’s specific requirements.

Initial Capital. to develop a scale for initial capital investment, 6 items were included, and they were adapted from (Dror et al., 2019) such as personal investment from entrepreneur, investment by loan from bank, investment from friends and relatives, investment from the general public, and perception of low or high investment.

Prior Experience. This scale was developed using 6 adapted components (Tramontano et al., 2021), such as managing tasks, managing time professionally, organizing activities, abiding by organizational policies, building trust and confidence, and use of different strategies.

R&D: This construct is measured by adapting 6 factors developed by (Brettel et al., 2012), which include flexible R&D process, expectations from R&D, priority of project target, adjustment of project target if R&D gave a surprise, potential setbacks or external threats in the R&D process, and meeting operational and technical performance in the R&D process.

Innovation Culture. The measures’ creation was inspired by the literature on innovation and strategic management. This study’s innovation culture scale was modified from (Dabić et al., 2018), such as updated technical equipment, budget for R&D, ownership of patents, success in process and product innovation, and development of new products and processes.

Economic Performance. This study utilizes net profit ratio (NPR) as an indicator of economic performance of MNEs (Goll & Rasheed, 2004) since most Pakistani firms use this proxy as a comprehensive tool for financial performance in financial reports, and it has been used by a significant number of prior studies (Khaddafi & Heikal, 2014). NPR is computed by deducting operational expenditures and taxation from gross profit and dividing that number by the net sales of that year.

Reliability and Validity

Table 2 provides the derived loadings, Cronbach alphas, composite reliabilities, and average variances extracted (AVE). The minimal loading should preferably be 0.70 or higher. However, the maximum permissible loading number is 0.50 (Le Bas & Sierra, 2002). For all components in the framework, composite reliability and AVE were examined. In respect of measuring reliability, composite reliability scores of more than 0.60 are satisfactory (Wynne, 1998). All composite reliability values were more than 0.60 (.886, .941, .948 and .918 respectively). The AVE range was adequate in reaching the desired range of 0.50 (Miron et al., 2004). The AVE values for initial capital, experience, R&D, innovation culture, and firm economic performance all achieved an adequate standard of 0.50. Cronbach’s alphas for the five constructs surpassed the 0.70 threshold mark (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Therefore, the measurement model is both valid and reliable.

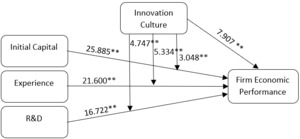

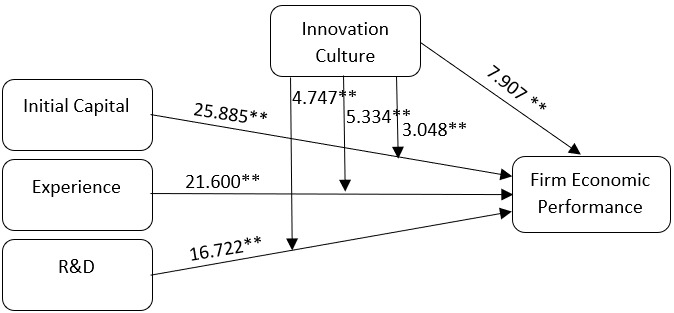

Figure 1 depicts the correlations between the variables used in this study. The following are the five variables: The independent components are initial capital investment, experience, and R&D; the moderating variable is innovation culture, and the dependent variable is firm economic performance.

Results

Model Testing

The study’s five components include initial capital investment, experience, research and development, innovation culture, and business economic performance in SMEs. Most of the indicators were adapted from prior research. The innovation variable was adopted from (Khattak, 2022). We examined 6 components such as “culture rewards behaviors that relate to creativity, organization’s culture encourages informal meetings and interactions, the culture encourages employees to monitor their performance, Employees take risks by continuously experimenting with new ways of doing things, the culture encourages employees to share knowledge, and culture focuses on teamwork long term performance to evaluate innovation culture” in SMEs. The term experience variable was derived from (Alliger & Williams, 1993). The initial capital investment, the amount spent on R&D, and business economic performance were derived from the annual report of SMEs, as well as the survey questionnaire. The resultant range of factors was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis in SPSS 26 using multiple regression. A hierarchical multiple regression analysis investigates the degree of variation in an endogenous variable that may be predicted by more than one exogenous variables and it is applied by several previous scholars in social science (Astivia & Zumbo, 2019; Bokhari & Aftab, 2022). The goodness of fit index (GFI) 2.149, the incremental fit index (IFI) 0.921, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) 0.065, the root mean square residual (RMR) 0.38, the comparative fit index (CFI) 0.97, and the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) 0.92, all suggested a good fit for the samples. These indices confirmed the key values for good data-model fit.

Table 3 displays the correlation values between all variables. The descriptive statistics and correlations, for the major portion, indicate in the appropriate direction and are as predicted. Firm economic performance is positively and significantly correlated with initial capital investment, experience, and R&D (r = 0.656, p < 0.01; r = 0.573, p < 0.01; and r = 0.628, p < 0.01). Firm economic performance has a favourable and considerably stronger correlation with innovation culture (r = 0.586, p < 0.01).

Table 4 explicates the findings of regression analyses to test the influences of initial capital investment, experience, and RED on SMEs’ economic performance, the effect of innovation culture on financial performance, as well as the moderating impact of innovation culture on the relationship of initial capital investment, experience, and RED and economic performance. The outcomes in Model 1 of Table 4 show that SME size has a constantly negative effect on the economic performance of SMEs at a substantial level throughout all Models. It suggests that small-size firms can perform better and can have higher effectiveness as compared to large-size firms. Prior literature produced varying findings regarding the effect of firm age on economic performance. However, firms with younger ages are more likely to grow quicker and produce better results than large organizations (Stella et al., 2014). According to the sampling data in Table 1, the proportion of small and medium-size entities is substantially larger than that of large-size firms and discovered in economic performance across all Models. These conclusions may suggest that organizations with fewer than 100 employees behave better than those with more than 100 employees and that firms with fewer than 500 employees behave better than those with more than 500 employees.

The outcomes for the SMEs in Table 4 provide support for all our hypotheses. According to H1, initial capital investment has a beneficial impact on SMEs’ economic performance (t = 25.885; p < 0.001). Consistent with H2, the association between prior experience and SMEs’ financial performance is significantly positive (t = 21.600; p < 0.001). We proposed in H3 that investment made in R&D has a relationship with SMEs’ economic performance, and finding scores indicate that our anticipation is correct, and R&D has a substantial positive impact on SMEs’ economic performance (t = 16.722; p < 0.001). Moreover, SMEs’ economic performance is affected by innovation culture as anticipated in H4, and the results in Table 4 supported our anticipation strongly (t = 7.907; p < 0.001). These findings suggest that Hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4 are strongly supported.

We investigated our moderating hypotheses further, and the results displayed in Table 4 provide significant support for our predictions. According to H5, when innovation culture is included as a moderator, the association between initial capital investment and SMEs’ economic performance is enhanced, and the results indicated significant support (t = 4.747; p < 0.001). We hypothesized in H6 that when innovation culture is incorporated as a moderator, the relationship between the prior experience of entrepreneurs and SMEs’ economic performance is strengthened, and we found substantial evidence for our hypothesis (t = 5.334; p < 0.001). Finally, R&D has a significant positive impact on SMEs’ economic performance, and this relationship is moderated by innovation culture, which strengthens this correlation (t = 3.048; p < 0.001), as shown in Table 4. Hence, these findings suggest that H5, H6, and H7 are strongly supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

The statistical examination of the complicated nature of this crucial strategic behavior is one of the issues in technology and innovation development, with the resource-based view and knowledge-based view functioning as effective structures for analyzing these phenomena. Despite knowing that financial capital, experience from previous learnings, and R&D are suggested as the primary sources of a firm’s economic growth (Artz et al., 2010; Désiage et al., 2010; Neumeyer & Liu, 2021), a detailed examination of the dynamic interactions between these features is required since significant gaps in this scientific field exist. Additionally, the dearth of academic evidence employing the aforesaid paradigms necessitates fresh and experimental conceptual and empirical studies, which is why this research has concentrated on providing quantitative findings and analysis on the issue. In accordance with prior research (Cooper et al., 1994; Park, 2011; Revilla & Fernández, 2012), the findings reveal that financial capital, experience, R&D intensity, and innovation culture all have a positive impact on SME economic performance. In particular, financial capital has the greatest impact on economic performance, preceded by experience, R&D, and innovation culture. These findings support earlier assertions published in previous literature (Geroski et al., 2010; Linder et al., 2020; Schumpeter, 2010).

Furthermore, this research attempts to contribute to the topic of resources management and firm performance by developing and investigating the moderating impact of innovation culture on the interactions between financial capital, experience, R&D, and firm economic performance. Such a form of moderating role might enhance the apprehension of the complexities of firm economic stability and growth. The findings demonstrate that innovation culture has a significant statistical moderating influence on the association between financial capital, experience, R&D, and firm economic performance. These findings support the prior empirical findings on the moderating impact of organizational cultural context in the interaction between innovation and firm performance (De Clercq et al., 2010).

The current study suggests an approach for enhancing the survival and economic performance of Pakistani SMEs. In this framework, innovation culture moderates the relationship between initial capital investment, prior entrepreneur experience, R&D, and economic performance. This framework specifically suggests that the innovation culture of SMEs increases the likelihood of the firm’s survival, and the relationship between initial capital investment, prior experience, and R&D is enhanced with the economic performance of SMEs. Having such a framework or resources could ultimately help SMEs accept innovation and find new opportunities to optimize their business processes. Consequently, SMEs can benefit from innovation in a robust economy. The capability to cultivate an innovation culture enables SMEs to respond in a way that safeguards their competitiveness in a volatile market. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can leverage the advantages of an innovation culture to operate their business effectively, efficiently, and with expected outcomes. People that live in an innovative culture can share their expertise with each other. The frequency of creating new ideas will be increased massively in information exchange. Therefore, SMEs will not need huge investment in R&D. Nevertheless, the acquired information should be interpreted in such a method that people can quickly absorb it and enhance their experience and expertise.

Beyond confusion, cognitive and behavioral factors have a significant influence in creating an environment conducive to innovation, which can lead to improved financial performance. The present study conducted an initial preliminary investigation by surveying ten SME entrepreneurs from diverse industries to gain support for the conceptual framework of innovation culture across SMEs in Pakistan. The survey findings proved that the principle of innovation culture is an integral part of innovation. It is in that entrepreneurs are motivated enough to explore different things regularly. For that purpose, an entrepreneur would have the required finance, experience, skills, and capabilities to effectively develop and execute new ideas. Nonetheless, the economic performance of SMEs will only prosper in the future years because nurturing profitability necessitates the absolute dedication of entrepreneurs to overcome employee resistance to transition to an innovation culture. Governing innovation is about promoting a culture in which innovative concepts are developed, acknowledged, and promoted, and obtaining such an innovation performance status is not a straightforward process without a comprehensive road map or strategies that are articulated and implemented.

To progress beyond a holistic approach to innovation culture, the component of experience sharing is very essential, as previous research demonstrated that the introduction of innovative knowledge is difficult to achieve, but it could revolutionize employee attitudes. Indeed, SMEs with a significant experience-sharing culture are effective at producing, gaining, and transmitting skills and experience, as well as adapting behavior to incorporate new abilities and ideas without overspending on R&D. Above all, SMEs ought to be responsible for translating knowledge into action. Based on the early findings, it is possible to conclude that innovation culture has an impact on R&D and can make it prevalent or unique in multiple aspects of firms (Duygulu et al., 2015). If maintained properly, an innovation culture may boost creativity and profitability. A critical component of innovative behavior is cultural openness to innovation, as demonstrated by the relationship between organizational culture and organizational learning and innovation. The innovation culture relates to the cultural awareness required to realize the necessity for SMEs’ economic performance. Future research should include both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, as well as a broader range of research methods, to increase the conceptual and practical significance of the research. Consequently, providing the exploratory research outcome to SME owners will include a unique perspective on why they need to understand the essence of an innovation culture to transition from conventional methods of doing business to innovative ways of conducting business.

Implications

Practitioners Implications. It is recommended that the entrepreneur reconsider the industry’s necessity for initial financial capital. Previous research indicated that the amount of capital decided to invest by the firm’s founder is not influenced heavily by sector differences but rather by the amount of first invested capital. There were disparities between companies based on industry categories, experienced versus inexperienced, and R&D engagement organizations. It has been discovered that manufacturers demand more start-up capital, higher prior experience, and higher R&D initiatives to thrive in the industry’s highly dynamic technological environment. It is also discovered that in certain specific industries, initial capital investment can be substituted for human capital (experience of the entrepreneur) since if the owner has previous industry knowledge, he would be capable of sustaining the firm efficiently. The retail and service industries require less initial capital, but the entrepreneur must have a high level of education and experience. Such firms do not need to engage in R&D operations, as manufacturing enterprises must. Those with a low level of initial capital investment and lower prior experience had a low chance of firm survival. Nevertheless, the survivability of firms with a high rate of former experience of the entrepreneur and a low level of investment was virtually comparable to that of firms with a minimal concentration of prior founder expertise and a greater level of investment capital. Those with a limited amount of initial capital investment and a lack of relevant experience had a lesser probability of surviving.