1. Introduction

Most economies rely heavily on micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) to drive economic growth, job creation, income generation, and innovation. MSMEs account for the majority of businesses and roughly 60% of all jobs worldwide (World Bank, 2022; WTO, 2020). In high-income countries, the sector accounts for approximately 55% of GDP and more than 65% of total employment (WTO, 2016), while in middle-income countries, the sector accounts for approximately 70% of GDP and 95% of total employment.

In the Arab world, MSMEs are estimated to account for over 90% of all businesses. In Saudi Arabia, the MSMEs make up majority of firms, accounting for about 99.6% of all private sector establishments and more than 60% of all private sector employees in the country (Roomi et al., 2021). However, the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has significantly slowed down the growth of the global economy and caused a massive unemployment rate, especially in small businesses (Hossain et al., 2022; OECD, 2020b; Sneader & Singhal, 2020; Wiggins & Hancock, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), reduced global economic growth in 2020 (Das et al., 2021), indicating that many economies, including emerging economies, are likely to continue to face economic challenges after COVID-19, which could have a long-term economic impact on the MSME sector. Due to the circumstance, numerous businesses have been forced to declare bankruptcy and close their doors, which has worsened the financial crisis and increased unemployment. According to GASTAT (2022), Saudi Arabia’s unemployment rate increased from 7.3% in 2021 to 9.7% in 2022. As a result, the government was forced to act quickly with a number of initiatives to support individuals and small businesses, which in turn had an effect on both market access and competition dynamics. However, the medium- to long-term viability of businesses has not been sufficiently maintained by the policy response and support measures.

Previous research on MSMEs focused on macroeconomic indicators such as GDP rather than micro or firm-level issues. Despite the fact that many studies conducted during COVID-19 focused on the financial performance of small businesses (Hanggraen & Sinamo, 2021; Hattiambire & Harkal, 2021; Pagaddut, 2021), research examining both financial and non-financial performance of MSMEs remains limited. There is currently very little impact analysis and survey-based research on the implications of COVID-19, particularly on Saudi Arabia’s MSMEs. As a result, it is necessary to broaden the existing body of knowledge about the financial and non-financial performance of micro, small, and medium enterprises, as well as identify the necessary supports for long-term business performance. The study will be extremely useful to the Saudi government and other decision-makers in determining the most effective government initiatives to address current and future COVID-19 epidemic issues.

Thus, the primary objective of this research is to assess how COVID-19 shocks and government initiatives affect MSMEs’ financial and non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the economic downturn, and to develop policy guidelines on mechanisms and approaches for stimulating the sector. To achieve this research objective, this study examined various industry types where MSMEs predominate, such as manufacturing, wholesale, retail, and services. This paper will help policymakers to develop the mechanisms, regulations and supporting strategies for MSME types that are most at risk and understand the kind of help needed to tackle the current and future challenges caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

2. Theory

2.1. Theoretical framework

This paper builds on dynamic capabilities theory to examine the consequences of COVID-19 outbreak on business performance of micro, small and medium enterprises in Saudi Arabia. The theory has become one of the most widely applied theoretical frameworks in management and strategic studies (Castaldi et al., 2011; Laursen et al., 2012; Zaheer et al., 2010). The dynamic capabilities theory was developed as a method for comprehending strategic changes (Teece et al., 1997) with the aim of defining the factors that underpin long-term success while also offering a framework for how businesses can gain and maintain competitive advantages in challenging circumstances (Alves & Galina, 2021; Wilden et al., 2016). According to Eisenhardt & Martin (2000), dynamic capabilities are the organizational and strategic practices that businesses use to acquire new resource configurations in line with how markets emerge, collide, divide, evolve, and stop.

This theory was created specifically to look at how an organization behaves and how that behavior relates to how well it performs. According to the theory, a company’s ability to adapt, integrate, innovate, and reconfigure skills, resources, and functional competences in a complex and quickly changing business environment is what gives it a sustainable competitive advantage (Colombo et al., 2020; Kump et al., 2019; Teece, 2014; Yeniaras et al., 2020). As a result, it places a focus on company-specific organizational and managerial processes to combat internal and external threats using a dynamic strategy. Dynamic capabilities theory, in contrast to other management theories, explains how businesses respond to environmental uncertainty as well as their resilience to deal with events that have already happened (Heredia-Colaço & Rodrigues, 2021). It has an impact on the performance of the company to the extent that it modifies the set of assets, operational practices, and competencies that in turn influence the firm’s financial performance (Helfat & Raubitschek, 2000; Zollo & Winter, 2002). The capacity to make rational decisions and react quickly to tumultuous environments remain major challenges for firms, particularly small-scale businesses (Eggers, 2020; Lee, 2009; Pavlou & El Sawy, 2011). In light of the COVID-19 pandemic’s unprecedented and unpredictable crisis, implementing dynamic capabilities theory increases the likelihood that an organization will succeed in the current environment (Bailey & Breslin, 2021; Clauss et al, 2021; Breier et al., 2021).

Without a doubt, the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted the global economy of micro, small, and medium-sized businesses. Because of this, it is essential to look into the extent of the disruption in terms of demand shocks, supply shocks, operational shocks, policy response, and the implications for the performance of small-scale businesses. As a result, the theory of dynamic capabilities will provide a strong theoretical foundation for the current study. In this regard, we suggest that MSMEs’ performance during COVID-19 is largely dependent on their capacity to establish, grow, or modify their resource bases.

3. Literature Review

COVID-19 threatens the financial security of both organisations and individuals (Miklian & Hoelscher, 2022; Sneader & Singhal, 2020), preventing working people from leaving their homes and businesses from meeting demand (Hossain et al., 2022; Smith-Bingham & Hariharan, 2020). Despite stringent government measures to combat it, the virus has exposed most businesses to major problems such as cash flow issues, closure of operations, layoffs, retrenchment, and reduced commercial transactions (Craven et al., 2020; Smith-Bingham & Hariharan, 2020; Wahyudi, 2014). As a result, several countries experienced a downturn (OECD, 2020b). Large-scale local and cross-border movement regulations, which result in the closure of national and local businesses as well as multinational corporations, also have an impact on business performance (Smith-Bingham & Hariharan, 2020).

Changes in business strategy, procedures, as well as demands to find new income streams and rebuild prospects, limit the viability of many MSMEs depending on the type of economic activity, size, and assets at hand (Cassia & Minola, 2012; Svatošová, 2017; Syed, 2019). It is critical that the impact of such issues be evaluated as soon as possible due to the current dearth of data that practitioners, policymakers, and other important stakeholders have access to.

3.1. Supply Side Impact on Business Performance

According to Fornaro and Wolf (2020), a pandemic is a negative shock to the growth rate and productivity. The COVID-19 crisis’ economic impact has been attributed to supply and demand shocks (Baldwin & Weder di Mauro, 2020). A supply shock is defined as something that reduces the economy’s ability to produce goods and services at predetermined prices. Pandemic supply shocks are commonly regarded as labor supply shocks. Several pre-COVID-19 studies focused on direct labor loss due to death and illness (McKibbin & Sidorenko, 2006; Santos et al., 2013), though some have also considered among other shocks, reduced labor supply due to mortality, morbidity due to infection, and the need to care for affected family members. The economic impact of social distancing policies in nations with such policies in place was significantly greater than the direct effects of mortality and morbidity. According to Maria del Rio-Chanona et al. (2020), social-distancing policies are more likely to have a larger impact than direct mortality and morbidity.

In terms of supply, the coronavirus pandemic had a devastating impact on MSMEs (Hossain et al., 2022; Juergensen et al., 2020). Governments and public health authorities around the world implemented restraint and mitigation measures, such as social distance, which inadvertently caused the controlled shutdown of entire economic sectors, particularly those that provide goods and services involving high levels of physical contact with other people. Due to social and physical constraints, the MSMEs saw a decline in revenue, which in turn caused a decrease in capacity utilization and a disruption in distribution activities. Businesses face a shortage of workers on the supply side, when people’s movements are restricted. As a result of the containment measures, more production capacity is lost, resulting in lower performance. Supply chains are also disrupted, resulting in component and consumer goods shortages (Lu et al., 2020; Miklian & Hoelscher, 2022; OECD, 2020a).

The ability of MSMEs to function has a significant impact on their ability to generate revenue, and as a result, a sudden and drastic drop in revenue can lead to significant financial difficulties. In addition to their concerns about the virus, clients are concerned about losing their savings and the possibility of losing their jobs due to long-term unemployment (Wisniewski et al., 2021). A number of industries, including travel and aviation, have suffered as a result. Small businesses are more vulnerable to social distancing than larger corporations (Adian et al., 2020; Fairlie & Fossen, 2021; Miklian & Hoelscher, 2022). Many have argued that if the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the supply shock will spread even more widely across economies (Das et al., 2021), affecting performance and growth.

Several studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of COVID-19-induced supply shocks on business performance (Barrero et al., 2020; Carletti et al., 2020; Guerini et al., 2020; Krueger et al., 2020; Schivardi & Romano, 2020). According to studies conducted on developing countries by Apedo-Amah et al. (2020) and Chetty et al. (2020), the COVID-19 shock had a persistent negative impact on sales, which subsequently affected overall business performance. The pandemic resulted in a significant number of business closures, job losses, and weakened financial positions (Bartik et al., 2020). Similarly, Bloom et al. (2021) used a panel survey of 2,500 SMEs in the US and discovered that over 40% of firms experienced sales drops, which has an impact on the performance and survival of small businesses. As a result, this study contends that supply disruptions can have a negative impact on business performance, particularly in the MSME sector. As a result of the above discussion, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: The supply side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H2: The supply side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

3.2. Demand Side Impact on Business Performance

The pre-COVID-19 literature on epidemics and discussions of the current crisis make it clear that epidemics have a significant impact on consumer spending and demand patterns. A demand shock is could be described as something that reduces consumers’ ability or willingness to buy goods and services at given prices. Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, demand was reduced due to a desire to avoid infection. Many consumers seek to reduce their risk of virus exposure, which reduces demand for products and services that require close contact with others. Many businesses have seen a drop in demand or an inability to fulfill orders as a result of the worldwide manufacturing plant lockdowns (Juergensen et al., 2020; OECD, 2020a; Rapaccini et al., 2020). Due to consumers’ desire to avoid infection, non-essential industries like entertainment, restaurants, and hotels also see a significant decline in demand (Brinca et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the demand shock was caused by income loss as a result of the pandemic, which reduced customer spending and consumption of all types of goods and services, including automobiles and appliances. MSMEs were hit the hardest, with many closing their doors either temporarily or permanently and laying off employees. The stand-alone MSMEs encountered significant logistical challenges. Independent consumer-focused MSMEs typically operate in markets with high demand elasticity. Customers’ job loss/insecurity, as well as their financial difficulties, have resulted in a dramatic drop in demand for many MSMEs (Keane & Neal, 2021; Mehta et al., 2021). Due to this and increased uncertainty about the pandemic’s course, demand for goods and services decreased across all industries, but especially in the MSME sector (Gourinchas et al., 2020).

Several studies have recently examined how demand shock affects a firm’s performance. According to a study by Mehrotra et al. (2020), the decline in demand significantly decreased the small businesses’ income, which ultimately had an impact on how well they performed. Similar to this, Adeola (2016) argued that the performance of SMEs is significantly impacted by external environments, such as economic, demographic, socio-cultural, financial, global, and social, which they are less able to influence (Lai et al., 2016). The greatest impact of the pandemic on MSMEs’ business performance was the loss of sales and revenues brought on by a decline in demand and the closure of non-essential business establishments (Velita, 2022). If MSMEs do not develop appropriate firm-specific strategies to resume operations and close a significant demand gap in the market, the long-term effects could be catastrophic (Tripathy & Bisoyi, 2021). The literature, however, lacks empirical studies on the connection between demand shocks and the financial and non-financial performance of MSMEs in emerging economies, particularly Saudi Arabia. Following these discussions, the following hypotheses were examined:

H3: The demand side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H4: The demand side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

3.3. Management & Operational Side Impacts on Business Performance

As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak and the ensuing lockout, a number of MSMEs have been forced to temporarily close their doors and cut costs (Block et al., 2022; Thorgren & Williams, 2020). In fact, MSMEs are less equipped to deal with shocks than large companies because they lack adequate managerial and financial resources (Bartik et al., 2020; Piette & Zachary, 2015; Prasad et al., 2015). According to the ILO, COVID-19 will increase unemployment by 5.3 million to 24.7 million people worldwide, warning that “sustaining business operations will be particularly difficult for small businesses” (ILO, 2020). According to Nurunnabi et al. (2020), 46% of Saudi enterprises reported a 100% decrease in regular sales/revenue, while 79% of MSMEs owners cancelled their business plans during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to many studies, the current pandemic poses a threat to the operational continuity of small-scale businesses; therefore, business owners and managers must be prepared to develop adaptive survival strategies to combat the effect of the COVID-19 epidemic (Hudecheck et al., 2020; Soumodip & Stewart, 2021).

A crisis, such as the COVID-19, may jeopardize the functioning and performance of a small business by disrupting its structures, operations, and capabilities (Williams et al., 2017). According to an International Trade Centre survey of SMEs in 132 countries, two-thirds of micro and small businesses stated the crisis has had a significant impact on their operations, and one-fifth are considering closing down permanently (ITC, 2020). Similarly, a McKinsey (2020) study on several surveys in a variety of countries found that small businesses could close permanently as a result of the pandemic’s disruption, though to varying degrees depending on the country. According to OECD analysis, the crisis is particularly affecting transportation, manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade, air transport, accommodation, food services, real estate, professional services, and other personal services.

Recent studies on small businesses have shown that unexpected shocks brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak have negatively impacted the operations of many businesses, causing significant changes in the performances of firms relative to expectations (Larcker et al., 2020; Obrenovic et al., 2020). The pandemic’s effects on business operations, activity disruptions, and firm closures have been found to have a negative impact on firms’ performance (Larcker et al., 2020). According to a study by Bartik et al. (2020) on business operations, operational shocks brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak have resulted in subpar business performance. However, despite the fact that there have been many studies on the effects of COVID-19 on MSMEs, very few have looked at the potential effects of operational shocks on MSMEs’ performances. Additionally, it has been reported that operational shocks have a significant negative impact on the revenue side of a company’s performance, casting doubt on its sustainability (Kells, 2020). MSMEs can prosper in the new normal reality by adjusting to the operational change and creating proactive strategies and measures. As a result, the following hypotheses were investigated:

H5: Management and operational side shocks will have a significant negative impact on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H6: Management and operational side shocks will have a significant negative impact on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

3.4. Policy Initiatives’ Impacts on Business Performance

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments around the world have implemented a variety of policies to assist micro, small, and medium-sized businesses (MSMEs). Many governments were quick to implement policies that allow MSMEs to postpone payments and obtain new lines of credit from government agencies and financial institutions (Belghitar et al., 2022; Didier et al., 2021), as well as provide relief for workers through specific pay and salary to aid short-term unemployment (Juergensen et al., 2020), whereas only a few economies introduced policies that were geared toward long term demand sustainability, such as new market alternative, innovation, and capacity building (OECD, 2020a). In Saudi Arabia, the government has implemented a series of policy responses aimed at assisting MSMEs, such as wage, tax, and rent subsidies, as well as direct lending for short-term survival. However, in order to achieve long-term resilience, MSMEs must be innovative in adapting their business model to capture potential demand, particularly in the worst-hit sectors, which experience massive loss of demand due to changes in customer behavior and the business environment during the pandemic.

It has been argued that MSMEs require a mix of policies to ensure their survival (Pedauga et al., 2022), but government assistance will be beneficial in mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 crisis (Liguori & Pittz, 2020). According to Adam & Alarifi (2021), providing external assistance to small businesses during the COVID-19 crisis is critical for MSMEs to identify new opportunities for growth and improve their performance, particularly those that have suffered the most from disruptions. External assistance is required to foster MSMEs’ innovation capacity, particularly in terms of integrating external knowledge and developing external collaborations (Pierre & Fernandez, 2018). As a result, the government’s role as a policymaker in expanding MSMEs’ market access became increasingly clear. The government may provide capacity building programs and direct mentorship to assist MSMEs in acquiring relevant skills and knowledge to meet rising demand in order to facilitate a smooth transition to a new business model. According to Rehman (2016), affirmative action programs can have far-reaching positive economic effects by improving minority employment and providing greater access to markets and capital, in addition to other positive social outcomes such as social justice and equality.

MSMEs’ resilience and performance have been harmed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the market is unable to allocate resources optimally in this situation, the government must act as a catalyst to strengthen or even encourage businesses to improve their competitive performance and market output (Mankiw, 2011; Osborne & Gaebler, 1992; Porter, 1985). Reviving the MSME sector will be extremely difficult without government intervention. Existing research on MSMEs has found a link between government policy and small business performance. They discovered that government policy has a significant impact on MSME performance (Ndiaye et al., 2018). Evidence also shows that, with or without a crisis, government response is an important factor in stabilizing and improving the performance of MSMEs (Antonescu, 2020; Gourinchas et al., 2020; Juergensen et al., 2020; Supardi & Hadi, 2020). During the pandemic, Fernandes (2020) emphasized the importance of government policies in resolving financial challenges in SMEs. Following these discussions, the following hypotheses were investigated:

H7: The policy initiatives will have a significant positive impact on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H8: The policy initiatives will have a significant positive impact on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

3.5. COVID-19 Shocks and Responses of MSMEs under Different Business Size and Type

Business size and sectoral differences are key differentiators in how firms respond to disruptive shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of their limited resources and vulnerable business models, the quarantine and disruption of non-essential activities as a measure to contain the COVID-19 pandemic has had a greater impact on MSMEs. The literature on small business recognizes the unique organizational characteristics associated with size, such as management structure and resource attributes (Hutchinson et al., 2021). Firms in different sectors, for example, are more likely to respond to crises in different ways, so some may be vulnerable while others are resilient to the shocks. Similarly, due to experience and capability, larger firms may be able to withstand shocks better than smaller firms. It is argued that small businesses face greater uncertainty and resource constraints than larger organizations, posing challenges to organizational resilience (Wishart, 2018). While prior research indicates that the paths to small business organizational resilience are numerous and diverse, the framework developed by Weick and Sutcliffe (2001) identifies four types of resilient capabilities in small businesses, namely resourcefulness, technical, organizational, and rapidity; however, small businesses fall short in all resilient capabilities.

Given that small businesses are more vulnerable to shocks (Marshall et al., 2015) and are more likely to close due to an unexpected crisis (Sydnor et al., 2017), tailoring a strategy to the current situation could help MSMEs survive the current economic downturn (Ratten, 2020). According to the findings, micro, small, and medium-sized business closures increased by 46.7% in micro and 30.6% in small and medium-sized businesses, respectively (Nurunnabi et al., 2020). Even after the pandemic, it is expected that many MSMEs will remain vulnerable to business risks because the “new normal” will necessitate changes in business and infrastructure management. To mitigate this risk, innovation has been identified as a critical component of business recovery during and after a pandemic (Caballero-Morales, 2021); however, MSME are frequently characterized by a lack of innovation. Smaller businesses are less innovative than larger corporations on average (OECD, 2018). Due to resource constraints and economies of scale, most MSMEs lack access and innovation capacity (Kurniati & Prajanti, 2018).

Previous research on small businesses has also found a direct link between firm size and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses (Biggs & Shah, 2006; Serrasqueiro & Nunes, 2008). Evidence suggests that firm growth, size, and age are very important in determining a firm’s future earnings capacity, success, and performance, particularly across different sectors; their crisis strategies and responses must be firm-specific or sector-specific (Antonescu, 2020; Gourinchas et al., 2020; Juergensen et al., 2020; Lee, 2009). Based on these discussions and the fact that the MSMEs sector is the most vulnerable sector in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic due to its size, scale of business, limited financial resources, and, most importantly, a lack of capacity to deal with something so unexpected (Béné, 2020; Sipahi, 2020), this study hypothesized that:

H9: The differences in business profiles will have significant impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H10: The differences in business profiles will have significant impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

4. Methodology

The majority of research on micro, small, and medium enterprises has used quantitative technique (Majoni et al., 2016), yet past studies employing a single methodology have found several drawbacks (Ibeh et al., 2006; Ismail & Kuivalainen, 2015). In order to collect adequate information from stakeholders of the MSME sector and provide strong evidence for the research model, this study uses a descriptive methodology that includes quantitative data (questionnaires) and semi-structured interviews (Yin, 2009), which is crucial when dealing with an unprecedented pandemic (Kraus et al., 2020). Nevertheless, more emphasis was placed on the quantitative methodology of research due to the nature of the current study. First, the quantitative data was collected and analyzed, then the qualitative data was collected and interpreted (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2007). This approach is important, as it allows us to exploit the strengths of both approaches to achieve more complete understandings of the impact of COVID-19 shocks on the performance of MSMEs in Saudi Arabia (Berkovich, 2018).

The results of the questionnaire phase enabled the proper interview guide to be used when approaching the interviewees. We made sure that the people we interviewed reflected the various traits of the MSMEs taking part in the study. In the qualitative method, a semi-structured interview was held with six participants, including 2 policymakers, a member of civil society, an academic at the professor level, a small business owner, and a senior employee of a medium-sized corporation. Strategic goals, policy actions, and the projected supports for corporate survival were the three key subjects of the interview guide. To enable better understanding, profound insights, and vigorous opinions being elicited, the interview questions were open-ended. The interviews were recorded, and data translated into texts and analysed qualitatively. By showing a distinction between the current predicament MSMEs are in and their strategies to survive potential future occurrence, a feature many prior studies have overlooked, this method enables theory to be extended. Each interview was conducted individually, and all interviewees’ identities and statements remained confidential. The interviews were conducted in July 2021 and generally lasted between 45-60 minutes.

4.1. Measures and Instrument

The prior research served as the basis for the measures of the constructs in this study. A questionnaire was designed to obtain data on the performance of micro, small and medium enterprises in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to the large-scale quantitative research, a pilot study was conducted to examine the suitability of the questionnaire and the clarity of the items. Four experts were consulted, including policymakers, an academician, and a small business owner in Saudi Arabia. They provided feedback, and the questionnaire was revised accordingly. The questionnaire’s structure was determined by the objective of the current study and was created to gather information for experimentally testable criteria. The impacts, types of problems, and kinds of supports needed were used to gauge the structures. The questionnaire consists of 43 items structured as follows: descriptive data of the respondents (11 items); demand side shocks (5); supply side shocks (6); management and operational side shocks (5); Policy initiatives (5); financial performance (6); non-financial performance (5). All the items were marked as mandatory in the online survey, so there was no incomplete or missing data. Each construct was evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale, “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). This range of options has been found to be highly reliable and valid in increasing the degree of consistency in scale measuring (Caruana et al., 2000).

4.1. Data Collection & Sample

This study employs a cross-sectional research design. The method is convenient, simple, and effective for gathering data to achieve research goals (Cavana et al., 2001). The micro, small, and medium-sized firms (MSMEs) in Saudi Arabia that have between 1 and 249 employees are the only ones covered by this study. Although an online survey was conducted throughout Saudi Arabia between May and July 2021, the final sample obtained only included respondents from eight of the country’s most populous provinces: Riyadh, Makkah, Madinah, Jazan, Aseer, Najran, Qassem, and the Eastern province.

The online questionnaire was created in both English and Arabic so that respondents could select the language in which they would most easily understand the questions. According to Bryman & Bell (2014), online survey is less expensive and speeds up the process of getting a lot of responses. More importantly, it is deemed appropriate given the COVID-19 restrictions and the social distance policy. This study’s respondents were primarily MSME business owners, managers, and employees.

Convenience random sampling technique was used to gather the data. For assistance with the online data collection, the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA), the Chambers of Commerce, and the Saudi Small and Medium Enterprises General Authority (Monsha’at) were contacted. The agencies were sent emails with a link to the online survey after giving their consent. Regular reminders were sent to the contacts via emails and phone calls to ensure high response rate. The questionnaire was completed by 380 respondents at the end of the survey period. The time required to complete the questionnaire was 8 to 10 minutes. This sample was deemed adequate, and the data was analyzed using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 1998; Sekaran & Bougie, 2003).

5. Data Analytical Techniques

Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) technique was utilized to analyse the data using Smart-PLS 3.2. PLS-SEM has been described as an excellent analytical method for assessing models since it reduces type II errors and can handle formative and complicated models (Chin, 1998). It makes the analysis of structural models that include multiple-item constructs with direct and indirect routes easier. Hair, et al. (2019), have argued that PLS-SEM is preferred over covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) because of its philosophy of measurement and goal of analysis (i.e., to forecast and create theory rather than to validate the theory). In line with the recommendations of Byrne (2016) and Kline (2011), the data was checked for multivariate normality before evaluating the model. Skewness coefficient (β = 2.447) and kurtosis coefficient (β = 51.686) were above the threshold score of 2 and 20 respectively when utilising Mardia’s coefficient technique, which indicates that data is not normally distributed. As a result, PLS-SEM is more suited for analysing the measurement and structural models, since bootstrapping (i.e., non-parametric inference) is used (Sarstedt et al., 2020).

5.1. Common method variance

The common method bias (CMV) can overestimate the strength of the correlations between the model’s variables because all of the responses came from the same place. Harman’s Single Factor (Podsakoff et al., 2012) and comprehensive collinearity assessment can be used to uncover this possible bias (Kock & Lynn, 2012). Results showed that the highest variable explained by an individual factor was 22.167 percent (<50 percent) according to the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2012). Since there was no collinearity in this study, a variance inflation factor (VIF) was found to be below 3.30 (Kock & Lynn, 2012). Overall, the findings show that CMV was not a problem in this research.

6. Result and Analysis

6.1. Demographic Profile of the Respondents

As shown in Table 1, 85.3% of the respondents in this study are male, while 14.7% are female. In addition, the majority of those polled (36.1 percent) are between the ages of 30 and 39, followed by those aged 40 to 49. (33.4 percent). 20.5% of the population is above the age of 50, while 9.2% are under the age of 30. The remaining 0.8% are all under the age of twenty. According to the survey, 64.5% of respondents have bachelor’s degrees, followed by masters at 17.4%, and secondary certificates at 8.2%. There are 38.2% business owners, 29.7% employees, and 27.4% managers among those who participated in the survey. More than four-fifths (68.6 percent) of respondents had worked for 21 years and above, followed by 11 to 15 years, 5 to 10 years and 16 to 20 years of experience. Table 1 shows that just 13.9% of them had worked for five years or below.

6.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Business Profiles

Among those who responded, 25% have been in business for more than 20 years, followed by 11-15 years, 6-10 years, and 0-5 years at 24.7%, 24.2%, and 17.4%, respectively, while only 8.7% have been in business for 16-20 years. There were 46.3% of enterprises with 6-49 workers (small enterprise), followed by 40.8% of enterprises with 50–249 (medium enterprise) employees and 12.9% of businesses with 1–5(micro enterprise) employees. According to the survey of these businesses, 43.4% of them are limited companies, followed by 35.3% sole proprietorship and 21.3% partnership. Most respondents’ businesses are physical (53.2 percent), followed by those that are both online and physical (39.5 percent), and only 7.4% of them are entirely online. There are also a large number of businesses in Riyadh, the Eastern region, Makkah, Asser, Qassem, Madinah, Jazan and Najran. As presented in Table 2, 40.5% of respondents’ businesses are service-based, followed by manufacturing (29.2 percent), retail (23.2 percent), and wholesale (6.8 percent).

6.3. Descriptive Analysis

Based on the descriptive statistics analysis in Table 3, it emerges that a mean result of 3.52 demand side shocks and a mean of 3.30 supply side shocks is evident in the MSMEs. The result also reveals a mean of 3.30 for management & operational side shocks, while non-financial performance of MSMEs has a mean of 2.75. However, financial performance displays a mean of 2.71. Similarly, policy response reveals a mean of 3.10 impact on MSMEs.

6.3. Measurement Model

There was an investigation on the construct measures’ internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability, and rho-A were used to check the structures’ reliability. A sufficient level of reliability is shown in Table 4 by values higher than the benchmark of 0.70 for Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability, and rho-A, indicating the measures are all reliable.

Indicator loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to measure convergent validity. When the indicator loadings reach the threshold of 0.50, the composite reliability is above 0.70, and the AVE is greater than 0.50, the study found that it had attained convergent validity as indicated in Table 4 (Hair et al., 2017). Four items (DC4, MC4, FP2, & FP3) were removed because they did not meet the criterion for convergent validity.

A heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of 0.85 and Fornell & Larcker criterion were used to evaluate discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2015). As illustrated in Table 5, the diagonal values (bold) are larger than the off-diagonal values (Fornell & Larcker criterion), and there was a poor correlation between all the variables (HTMT). This reaffirmed discriminant validity of the constructs. There was no evidence of multicollinearity among the predictors in Table 6, which demonstrates that all constructs had variance inflation factor (VIF) values less than the benchmark value (Becker et al., 2015; Miles, 2014).

6.4. Structural Model: Hypotheses Testing

Five different types of predictive power are used to examine the structural model: in-sample predictive power (also known as the Coefficient of determination, R2) (Hair et al., 2019), effect size (f2) (Cohen, 1988), predictive accuracy (Q2 and PLS-predict), and path coefficients (Shmueli et al., 2016, 2019). The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to cross-check the lateral collinearity issue. Based on the VIF values which are below the cut-off score as shown in Table 6, multicollinearity does not appear to be a problem in the current study (Becker et al., 2015; Hair et al., 2017).

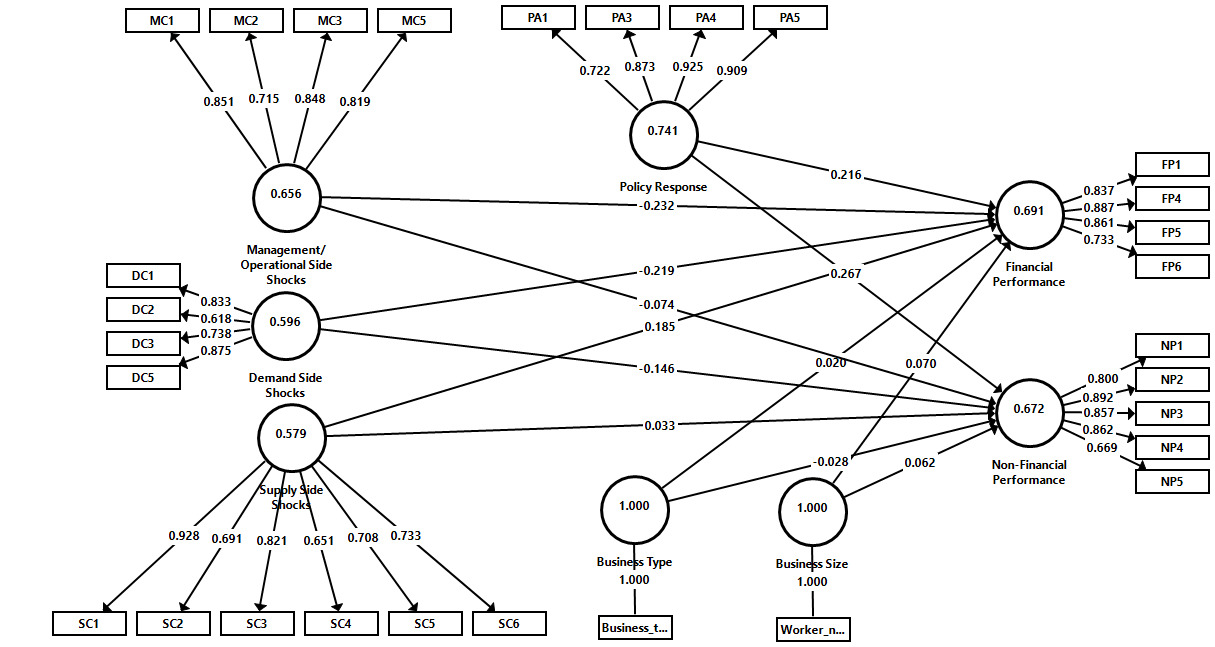

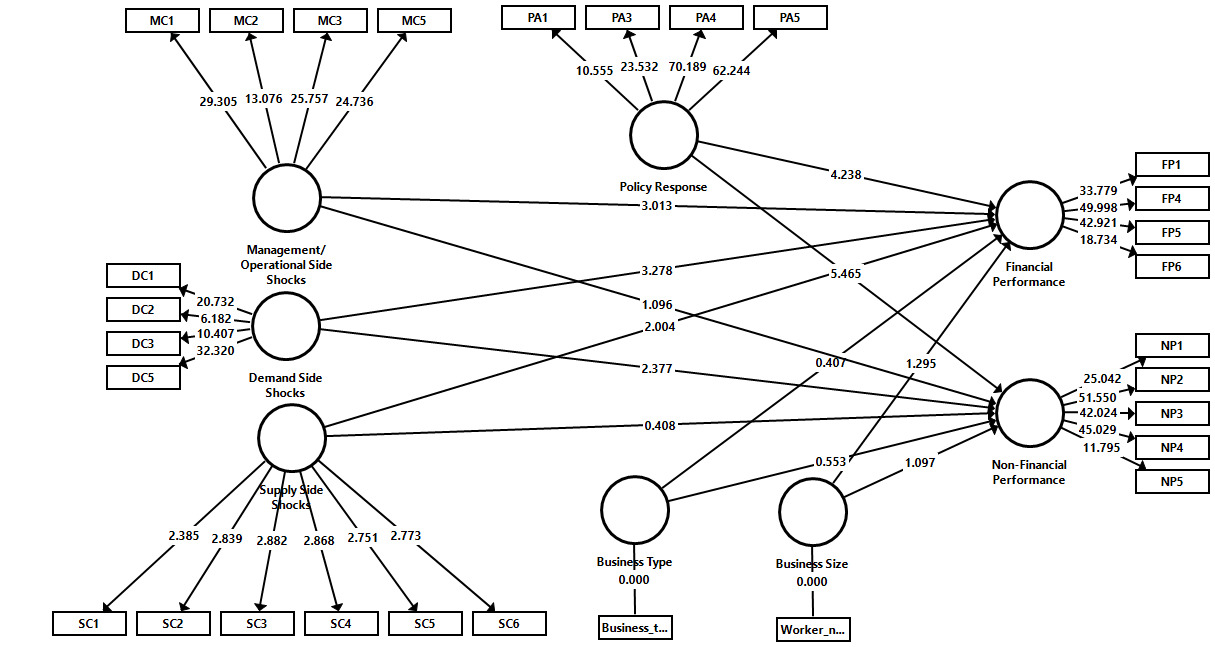

To assess the structural model’s significance for path coefficients (95 percent bias-corrected and accelerated), t-values, p-values, and confidence intervals were used. A bootstrap re-sample technique with 5000 sub-sample iterations was used to assess the structural model’s hypotheses. Table 6 and Figure 2 show the correlations between the variables. All three of these hypotheses were found to be true (H1: β = -0.219, p = 0.001), and they were all shown to be associated with financial performance (H2: β = 0.2322, p = 0.001) and (H3: β = -0.185, p = 0.023), hence they were all supported. Only Demand Side Shocks were found to be a significant predictor of non-financial performance (H4: β = -0.146, p = 0.009) and thus supported. Non-financial performance is unrelated to management/operational side shocks or supply side shocks (H5: β = -0.074, p = 0.147) (H6: β = 0.033, p = 0.342), hence these hypotheses are not supported. Both financial and non-financial performance (H7: β = 0.216, p = 0.000) were supported by the policy response (H8: β = 0.267, p = 0.000).

The next stage was to look at the prediction power of the in-sample data (coefficient of determination, R2). According to the results, exogenous variables (Demand Side Shocks, Management/operational Side Shocks, Supply Side Shocks, and policy response) account for 15% of the volatility in financial performance (refer Table 6). Also, Demand Side Shocks, Management/Operational Side Shocks, Supply Side Shocks, and Policy Response account for 11% of the variance in non-financial performance. The construct’s effect size was then calculated using Cohen’s (ƒ2) (Cohen, 1988). It is safe to state that any effect size (ƒ2) number greater than 0.02, 0.15, or 0.35 is considered to have a moderate or significant impact, respectively (Cohen, 1988). When considering the p-values for the two exogenous variables, there were only two modest effects for the two endogenous factors, as shown in Table 6.

To determine the structural model’s predictive accuracy, the blindfolding technique was used by computing Q2 values (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974). Explanatory variables (i.e., financial and non-financial performance) are shown in Table 7 to be predictive of the model (with Q2 values above zero) (Hair et al., 2017). “An innovative approach for measuring the model’s out-of-sample prediction” was used to examine the model’s predictive accuracy. PLS-predict for out of sample prediction (Hair et al., 2019; Shmueli et al., 2019). A PLS predict evaluation in Table 6 shows that the PLS-SEM estimation produced several Q2 values that are greater than the LM model, indicating the model’s predictive relevance.

Predictive results can be described by following Shmueli et al. (2019)’s criteria, which show that some endogenous variables in the PLS model provided the lowest predictive error compared to LM model, indicating medium predictive power. Finally, the study used the standardised root mean square residual to evaluate the model’s fit (SRMR). According to Hu and Bentler (1999), this paper’s SRMR (statistical reliability margin of error) is 0.064, which is less than 0.08.

6.5. Moderating Impact Analysis

To ascertain the moderating role of policy response on the relationships between demand side shocks, supply side shocks, management and operational shocks, and financial and non-financial performance, moderation analysis was performed by taking into consideration the interaction effect of policy responses (Chin et al., 2003; Henseler & Chin, 2010). The results of the moderation analysis are presented in Table 6 and Figure 3. As shown in the results, there was a significant interaction effect between management and operational shocks and financial performance of MSMEs (β = 0.122, p = 0.031) with a medium impact size of 0.240. Similarly, the results show that policy response had a moderating effect on the relationship between management and operational side shocks and non-financial performance of MSMEs (β = 0.120, p = 0.041) with a medium impact size of 0.225. In contrast, the role of policy response on demand side and supply side shocks for both financial and non-financial performance was not significant.

Figures 4 and 5 depict the pattern of interaction between management and operational side shocks, financial performance, and non-financial performance (Dawson, 2014). The interaction plots illustrate that the correlations between management and operational side shocks, financial and non-financial performance were higher when policy response was high, which suggests that higher level of policy response will strengthen the relationship between management and operational side shocks, financial and non-financial performance of MSMEs.

6.6. Qualitative Analysis

This section presents the result of the interviews conducted. Interview responses are presented and discussed based on related topics. In order to find out the opinions that stakeholders have regarding the policy response by the government on the impact of COVID-19 on MSMEs and their suggestions on how to combat the effect during and after COVID-19 pandemic, three open-ended questions were analyzed. Table 8 presents the characterization of the participants.

6.6.1. General view of the actions taken at policy level

Opinions and views expressed by the participants in this study reveal different interpretations, and it can be stated that less than 50% of respondents agreed on the adequacy of the government’s financial stimulus and non-financial support packages to survive COVID-19. The policy response by the government is adjudged to be fairly adequate. Based on the interview held with the different stakeholders in the MSME sector regarding how they perceive the government policies and programs on COVID-19, the participants consider it to be generally effective but need to keep working on how to improve the policy actions so that MSMEs can develop resilience during crisis. They understand that many MSMEs would have done worse without the policies and programs initiated by the Saudi government. The interviewees also say that “about 23% of the MSMEs received soft loans and tax breaks, while 41% benefited from financial injection policies and programs”. They therefore consider government policy as an efficient tool to enhance performance and ensure business continuity of the MSME firms in Saudi Arabia, however, not adequate. In contrast, they highlighted that some business enterprises have continued to operate because of alternative sources of funding, such as private help, reduced expenses, and continued demand for their goods/services. They also, highlighted that many small-scale businesses are not aware of many of the government initiatives to support the sector.

6.6.2. Expected support systems

Based on the interview, concerning the firms’ expected support from the government, in this regards, the interviewees believe the government can solve this problem to meet the expectations of the people in this sector by considering “both the financial stimulus and non-financial support are of crucial importance and only make sense if taken together, as giving more importance to one would make it impossible to achieve the other”. They suggest that the government can ease financial pressures and non-financial challenges on MSMEs by injecting more money, more soft loans, wages support, reduced interest rates, deferment programs, training and skill acquisition program, and overall reduction in government fees. They believe that this will save a number of businesses which can continue to trade and have customers, retain a profit margin, encourage savings, and make growth possible.

6.6.3. Sustainable actions to stimulate the MSME sector

As stakeholders in the sector, the interviewees consider science, technology, and innovation policies important for MSMEs to access and profit from. When asked about how the government can ensure business sustainability, they state “in the long-run, adequate policies should be put in place by the government to fund the important public and private sector institutions. More so, different innovation strategies to cope with any turbulence should be implemented by the various kinds of companies”. They also suggest that “sustainable solutions to the MSMEs problems require a bottom-up policy-making process which encourages stakeholders’ participation, networking, making alliances and partnerships with policy-makers and other relevant institutions”. Therefore, MSME firms need to develop their capacities to pay their staff, suppliers, tax, etc., and be treated as fairly as the large corporations operating in Saudi Arabia.

7. Findings and Discussion

H1: The supply side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H2: The supply side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Financial performance shocks can be attributed to three types of factors: supply-side, demand-side, and management-side. The non-financial performance of Saudi Arabian MSMEs was found to be unaffected by supply side shocks. According to the dynamic capabilities theory, the results suggest that the dynamic capabilities theory effectively plays a fundamental role in the emergency circumstances of the pandemic, enabling an instantaneous response to the crisis situation created by the COVID-19 in the supply chain (Yeniaras et al., 2020). However, the finding is contradicted by Fornaro & Wolf (2020), Miklian & Hoelscher (2022), Adian et al. (2020), Fairlie, & Fossen (2021). This implies that the non-financial performance of Saudi MSMEs, which could be attributed to the nature of business, the categories, the years of establishment, and the sector in which each firm operates, as well as the economic conditions in the country that are imposed by the COVID-19 outbreak, is not particularly impacted by supply side shocks as an economic shock. The non-financial performance of MSMEs is significantly impacted by all of these factors.

In the current study, however, supply side shocks had a significant impact on the financial performance of Saudi MSMEs. As a result, respondents regard supply side shocks as more serious than other economic crises that have disrupted business activities and expansion. This finding supports previous research conducted by (Apedo-Amah et al., 2020; Chetty et al., 2020; Maria del Rio-Chanona et al., 2020; Bloom et al., 2021; Das et al., 2021). It is worth noting that this feature has mostly emerged in empirical studies on the impact of the economic crisis on business performance (McKibbin & Sidorenko, 2006; Santos et al., 2013).

H3: The demand side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H4: The demand side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

According to Mehrotra et al. (2020) and Velita (2022) studies, demand shocks have significant effects on the performance of firms, whether they are positive or negative depending on the circumstance, the industry, and the forms. It was found that demand side shocks had a significant negative impact on the financial performance of Saudi Arabian MSMEs. The nature of the business, the categories, the years of establishment, the industry in which the firm operates, as well as the economic conditions in the country that are brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak, all lend support to demand shocks in the current study. The financial performance and sustainability of MSMEs are significantly impacted by all of these factors. According to the research, demand side shocks may have an impact on the financial performance of Saudi Arabian MSMEs. Contrary to supply side shocks, non-financial performance was significantly predicted by demand side shocks. This outcome is consistent with earlier research from Lai et al. (2016), Keane & Neal (2021), and Gourinchas et al. (2020).

H5: The management & operational side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H6: The management & operational side shocks will have significant negative impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

In contrast to other studies by Obrenovic et al. (2020) and Larcker et al. (2020), which asserted that management and operational side shocks are significant predictors of business performance, it was discovered that management and operational side shocks had no significant impact on the non-financial performance of the Saudi Arabian MSME sector. This finding aligns with the dynamic capabilities theory as well. This discovery offers a foundation for empirically assessing the dynamic capabilities theory’s contribution to helping MSMEs maintain performance. Despite the fact that the pandemic challenges are widespread, many MSMEs have a higher chance of being able to deal with their effects (Obal & Gao, 2020; Zafari et al., 2020). As a result, MSMEs have a greater chance of succeeding and surviving the pandemic due to their dynamism and increased competence (Bailey & Breslin, 2020). The outcome might also be a result of the business profiles of many of the long-running MSME firms sampled in this study. The majority of respondents have a lot of experience in this field, which makes them more adaptable and resilient during the COVID-19 outbreak.

On the other hand, management and operational side shocks had a significant impact on the financial performance of the Saudi Arabian MSME sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. This result is consistent with earlier research on the effect of operational shocks on the financial performance of MSMEs. These studies provided evidence that, in comparison to other factors influencing MSMEs’ performance, managerial and operational shocks are very important (Bartik et al., 2020; Kells, 2020; Williams et al., 2017). In addition, using moderating analysis and accounting for the interaction effect of policy response, the bootstrap findings show that policy response moderated the path between management/operational side shocks and financial and non-financial performance with a medium effect size of (β = 0.240) and (β = 0.225), respectively. No significant moderating effects on demand and supply side shocks, financial and non-financial performance were seen in the policy response. As a result, Dawson’s (2014) proposed interaction plot was utilised to show that the connections were stronger when policy response was greater.

H7: The policy initiatives will have significant positive impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H8: The policy initiatives will have significant positive impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

The relationship between policy initiative and performance, both financial and non-financial, was established. This result is consistent with research by Antonescu (2020), Adam & Alarifi (2021), Belghitar et al. (2022), Juergensen et al. (2020), and Ndiaye et al. (2018). This speaks to the Saudi Arabian government’s willingness to support the MSME sector as well as the financial stimulus package and non-financial assistance policies put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. All of these factors have a significant impact on the overall performance of Saudi Arabian MSMEs both during and after COVID-19.

H9: The differences in business profile will have significant impacts on MSMEs’ financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

H10: The differences in business profile will have significant impacts on MSMEs’ non-financial performance in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

An important connection between the financial performance of small and medium-sized businesses and this study’s findings is not readily apparent. This result is consistent with a study by Affandi et al. (2020), which discovered that small and medium-sized businesses did not show any notable results. The size of the firm does not seem to have a significant impact on the non-financial performance of MSMEs. The current study provides evidence that dynamic capabilities continued to have a positive impact during COVID-19. Contrary to widely accepted findings in the literature, this study offers compelling evidence on firm size (Eggers, 2020; Lee, 2009). In this study, the findings on MSME size extend dynamic capabilities theory by confirming a new frontier situation that suggests that smallness during a crisis aids rather than hinders performance, in contrast to the previously established position that a firm’s size limits its performance.

Due to alternative sources of funding and support, such as private aid, lower costs, and continued demand for their goods and services, the majority of MSMEs in Saudi Arabia were able to continue operating despite the government’s support measures and policies during the COVID-19 epidemic. Rules and initiatives for MSMEs during the COVID-19 outbreak are effective, but they fall short, as Nurunnabi et al. (2020) noted. The way policy is made in the future will be influenced by a careful examination of this issue.

The COVID-19 economic shock has had a wide range of effects on the financial and non-financial performance of MSMEs. Government interventions typically succeed in reducing financial consequences for businesses that have been in operation for five years or less, sixteen to twenty years, sole proprietorship mode of business, service provider business, and microbusiness. This is in line with the findings of Antonescu (2020), and Gourinchas et al. (2020). Policy initiatives have also been successful in reducing the non-financial effects of sole proprietorship, manufacturing, and medium-sized businesses. In this study, the impact of COVID-19 on financial performance of small and medium-sized businesses, as well as non-financial performance of micro and small businesses, is not statistically significant. As a result, micro, small, and medium-sized businesses around the world must undergo a paradigm shift not only to survive the COVID-19 crisis, but also to thrive in the post-COVID-19 era.

8. Conclusion

Using data from 380 MSMEs across Saudi Arabia, this paper assessed the effects of the COVID-19 economic crisis on MSMEs’ business performance. The effectiveness of government assistance initiatives during the pandemic was also empirically evaluated. The findings indicate that demand side shocks, management/operational side shocks, and supply side shocks all have a significant impact on MSMEs’ financial performance. The findings, on the other hand, show that only demand side shocks have a significant impact on non-financial performance, whereas management/operational side shocks and supply side shocks have no effect. Financial and non-financial performance are inextricably linked and influenced by policy responses. It was discovered that the Saudi Arabian government’s policies and support programs for MSMEs are unable to mitigate the negative impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on demand and supply side shocks, as well as financial and non-financial shocks. These findings have important implications for the dynamic capabilities theory, policymakers, regulators, and MSMEs. The current study’s findings will undoubtedly contribute to the body of knowledge on the financial and non-financial performance of MSME firms in the future. Furthermore, the current study extends dynamic capabilities theory to a new area of research that has yet to be empirically investigated, particularly in Saudi Arabia.

However, the study also offers policymakers and other stakeholders in the MSME sector insights into the factors that must be reduced in order to improve the performance of MSME firms, including demand and supply side shocks, managerial and operational side shocks, and policy response. Government support programs and policies during the COVID-19 pandemic have helped many MSMEs in Saudi Arabia to some extent; otherwise, business activities in this sector would have been significantly impacted. Surprisingly, many MSMEs took the initiative to reevaluate viable business approaches so that they could continue to operate with the help of alternative funding and support sources, like private assistance, lower costs, and ongoing demand for their goods and services. The results demonstrated that while government policies and programs are somewhat effective, they are insufficient in reducing the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on MSMEs. Given the sizeable contribution the MSME sector makes to the Saudi economy, it is crucial that the authorities review the policy measures to provide more support and opportunities for the MSMEs through alternative funding mechanisms like crowd funding, bond issuance, and capital development to lessen the effects of the pandemic. More importantly, the government needs to play a big part in managing the economic crisis by conducting credit risk assessments to find genuine MSMEs that need financial and non-financial assistance and steer clear of zombie businesses.

The devastating effects of COVID-19 can also be lessened by offering various forms of household assistance, such as unemployment or underemployment benefits. Given their proximity to the pandemic, it is clear that “coal face” MSMEs are not being contacted for their opinions on policy initiatives. To reach consensus on the best solutions, a forum for business owners to discuss issues should be established. Finally, improving MSMEs’ performance through a variety of strategies will benefit not only the sector’s stability and sustainability but also the health of the Saudi economy as a whole.

9. Limitation and future research

While this paper has highlighted some of the implications of COVID-19 on the performance of MSMEs in Saudi Arabia, some limitations in the paper allow for further consideration. First, the survey in this study was conducted over a short period of time, resulting in a small data sample. As a result, future studies should employ larger sample size surveys that cover a broader range of economic sectors. Second, given that this study only examines the economic consequences of COVID-19 on the MSME sector, it is advised that future lines of inquiry build on the findings of the present investigation by examining the effects of the new working environment brought about by COVID-19 as well as the effects of manager/employee and customer safety and health on business performance during and after the pandemic. Third, while this study only focuses on Saudi Arabia, further research into a cross-country study that can be conducted in Middle Eastern countries.

Acknowledgement

The authors express their profound gratitude to the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) for the grant given for this project under the Joint Research Program 2021. We are also deeply grateful to the respondents and the interviewees who participated in this study.

.png)

.png)