Introduction

Bewildered by galloping globalisation, growing competition has urged firms to incessantly force themselves to turn their organisational structures, systems, and techniques into something more advanced (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Ribeiro et al., 2020; Waheed et al., 2020). Increasingly, the literature echoes that innovation is the salient factor for everlasting firm achievement, especially in turbulent times (De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010; Lyon & Ferrier, 2002; Shalley et al., 2009). Researchers viewed innovation as a notable competitive strategy that permits firms to reform their structures, systems, and techniques to augment their growth and competitive position (Dalota & Perju, 2010; De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010; Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2015). Expressly, firms should adopt a high degree of complexity and high speed of change to survive in volatile conditions (Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2015). In these specific conditions, firms should quickly innovate to cope with these challenges and harness new products and market openings better than non-innovative firms (Chen & Huang, 2009; Diaz-Fernandez et al., 2017). The logic behind that is that by presenting new products, processes, and technologies, firms can expand, adapt and reinvent themselves, which, in return, evoke organisational performance (Shalley et al., 2009). According to James et al. (2013), a firm can benefit from innovation in several ways: higher productivity, competitive advantage, new markets, higher revenue, and long-term survival.

However, innovation requires some specific atmosphere for efficacious growth (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008). Innovation as a source of competitive advantage, various studies have explored the underlying determinants of the firm’s innovative capability (Chang et al., 2011). The literature reflects that the firm’s internal and external factors are the key determinants of innovation effectiveness. Moreover, organisational culture, organisational strategy, systems, management style, and human resource management (HRM) are identified in the literature as key influencers in a firm’s innovativeness (Adla et al., 2019; Chen & Huang, 2009; Lertxundi et al., 2019; Ling & Nasurdin, 2010; Shipton et al., 2005, 2006). Florén et al. (2014) emphasised that individuals are creators of ideas and logically play a substantial role in innovation. Despite this, exploring what makes individuals more innovative is essential in understanding how individuals can be encouraged to capitalise on these ideas for innovative results (Bos-Nehles & Veenendaal, 2019). The role of human resource management (HRM) has become more salient in seeking ways to augment innovation outcomes (Shipton et al., 2017). Studies are beginning to investigate the nexus of HRM practices in facilitating organisational innovation.

Grippingly, the firm’s resource-based view (RBV) and Human Capital (HC) theory claim that developing employee capabilities is critical for innovation and to reap sustainable competitive advantage (Wright et al., 2001; Wright & Boswell, 2002). Literature declares that HRM is the antecedent of innovation (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008). Besides, scholars propose that HRM aids in developing organisational capabilities, an “instrumental variable” of competitive advantage. Similarly, HRM can contribute to organisational capabilities by reinforcing role behaviours that evoke firm innovation (Chen & Huang, 2009). Innovation is recognised as one of the organisational capabilities (Waheed et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2001). Thus, innovation is a well-recognised catalyst for economic growth, and human capital is the critical determent underlying the innovation process (Chen & Huang, 2009; Haneda & Ito, 2018; Ling & Nasurdin, 2010; Waheed et al., 2019). Therefore, a firm’s HR needs to ensure that employees’ competencies and engagement are part of high innovation performance because innovative and engaged individuals can accomplish rigorous goals and leverage firm innovation in all circumstances (Waheed et al., 2019).

Surprisingly, this poses a significant challenge for businesses and nations such as Sri Lanka, as companies strive to compete in the global market and increase productivity by fostering high-performance workplaces. It is hardly surprising that in Sri Lanka, the availability of human resources is relatively high. The most paradoxical part is its efficient and effective management to evoke firm innovation (Gamage & Takayuki, 2013). It is essential to present and use the proper human resource practices that appeal to the employees when attracting and retaining creative individuals (Chen & Huang, 2009). Scholars declare that firms’ strategic approach to HRM is influential in reaping significant positive work-associated behaviours among individuals and significantly producing firm innovation (Ling & Nasurdin, 2010).

Shipton et al. (2017) state that many studies are now beginning to discover the role of HRM in nurturing innovation; however, the empirical evidence remains contradictory, and the theory is fragmented. Moreover, the relationship between HRM and innovation has been studied in literature from a contingent perspective (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005). Little published works on HRM practices and firm innovation are found in HRM journals (Laursen & Foss, 2003). Ironically, there have been very few empirical studies; nevertheless, their conclusions are heterogeneous, and most have given attention to US and European firms (Dalota & Perju, 2010; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005). Consequently, there is an apparent lacuna in the literature, specifically for developing countries like Sri Lanka, studies on firm innovation thus far in the infancy stage (Wan Jusoh, 2000). It is evidenced that scholars have grasped a vast range of knowledge about the intimacy between HR practices and firm performance in finance (Hutchinson et al., 2003); still, the extent to which HRM promotes firm innovation is lacking. Thus, a need to discover which HRM practices or a blend of practices are related to innovation at the firm level (Shipton et al., 2006). Consequently, HR Managers are now encountering a substantial risk of developing and launching the practices essential to simplify innovation.

Paradoxically, empirical research on the innovation and performance relationship in SMEs shows debatable fallouts (Rosenbusch et al., 2011), and innovation is a significant trouble for the growth of SMEs (Krishnan & Scullion, 2017). Different phases of innovation are grounded on a few internal and external contextual elements linked to the exclusive characteristics of SMEs, viz, intense proximity, workforce versatility, and organisational adaptability. Fréchet and Goy (2017) delineate that if managers develop a strategy of innovation that is both formalised and planned can produce a better result. Importantly, SMEs’ innovation strategy is nascent in nature. Further, SMEs do not consider the importance of HRM to reap a competitive advantage (Curado, 2018; Ogunyomi & Bruning, 2016). Strobel and Kratzer (2017) reported that HRM challenges appear critical in an SME context because human resources have been viewed as one of the essential hampers to innovation performance.

Previous research studies highlight that the poor management of people in small firms produced diminished productivity and significant turnover rates, which caused small firms’ failure (McEvoy & Buller, 2013). Marlow et al. (1993) posit that the efficacious management of individuals in the workplace is growing as a critical variable in SME performance. They further testified that SMEs do not frequently embrace HRM practices to reap a competitive advantage over their rivals. In Sri Lanka, several policies, techniques, and interventions are recommended by various SME advocates to elevate the sector. Despite this, quite a few academics and practitioners have holistically ignored the human part of business management in SMEs.

Therefore, the present study attempts to answer the following research questions: (a) To what extent do HRM practices (recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, compensation and reward) augment product, process and administrative innovations? And (b) Which HRM practice is the most influential in promoting firm innovation?

In response to those research questions, the present study explores the role of HRM practices in promoting firm innovation in SMEs in Sri Lanka. Based on the broad aim of the study, the following objectives are expected to be attained;

-

To examine the relationship between HRM practices (recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, compensation and reward) and firm innovation (product, process and administrative).

-

To determine the most influencing HRM practices in promoting product, process, and administrative innovation.

Therefore, the present study investigates the relationship between HRM practices and firm innovation. The article is organised as follows. After this introduction, the voids have been identified by reviewing the succinctly expressed literature under research problems. Then, a literature survey on HRM and innovation and SME firms is introduced. After that, the pre-owned research strategy is clarified in the methodology part, and the data acquisition and investigation techniques are delineated. In the following segment, the principal findings from the data are examined. At last, the article closes with the conclusions and implications just as the future research lines.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Recruitment, Selection, and Innovation

Recruitment and selection are critical HRM practices for innovation success (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Mumford, 2000). In the innovation process, adequate staffing becomes one of the vital sources of generating new ideas, thus fostering innovation in firms (Chen & Huang, 2009). The ideal recruitment and selection practices enable the firm to recruit capable and creative individuals who, in return, contribute to the innovation process (Chang et al., 2011). Organisations face a high degree of uncertainty and inconsistency in developing the innovation process (Curado, 2018). Thus, they require creative individuals who are adaptable, risk-taking, and accepting risk (Stjernholm Madsen & Ulhøi, 2005). Therefore, firms should focus on these qualities in the staffing process (Taylor & Fowle, 2002). Firms adopt creative capabilities and innovative qualities as recruiting and selecting criteria, and their individuals are willing to reveal diversified ideas and engage in more innovative behaviour (Chen & Huang, 2009). Firms should use high-performance HR practices to provide a relevant climate for employees (Laursen, 2002). Therefore, they can transmit their knowledge to foster innovation. Those HR practices encapsulate care in the selection processes (Collins & Smith, 2006). Recruitment gives more special meaning to stay connected between individual and company culture. Subsequently, the significant degree of execution of recruitment that connects individual-firm fit is expected to bring about high firm innovation (Tan & Nasurdin, 2011). Scarbrough (2003) found that selecting individuals with relevant skills and the necessary attitude to perform the task permits firms to integrate knowledge from various sources and evoke innovative idea creation and execution. Chang et al. (2011) propose that management scholars have assessed how recruitment and selection stimulate firm innovation. Mumford (2000) claimed that innovation relied on the capacity of individuals to create new ideas, and that ability affects creative problem-solving.

Only a few studies have explored the relationship between individual HRM practices and types of innovation. Using a sample of 240 manufacturing firms, Michie and Sheehan (2003) found that recruitment and selection practices positively affect product and process innovation. A study conducted by Jimenez-Jimenez and Sanz-Valle’s (2008) in 173 Spanish firms shows that product, process and administrative innovation are significantly positively associated with the training interventions of organisations. From a sample of 171 manufacturing organisations in Malaysia (Tan & Nasurdin, 2011) found that HRM practices tend to have a positive impact on firm innovation. However, the studies are insufficient to make firm decisions on how recruitment and selection impact types of innovation. Moreover, recruitment and selection practices vary across countries and organisations. Thus, it can be hypothesised,

H1: Recruitment and selection practices positively impact product innovation.

H2: Recruitment and selection practices positively impact process innovation.

H3: Recruitment and selection practices positively impact administrative innovation.

Training, Development, and Innovation

Training facilitates individuals’ exposure to diverse knowledge and openness to innovative new ideas (Bauernschuster et al., 2009; Jaw & Liu, 2003). Dostie (2018) claimed that few studies had examined training as a predictor of firm innovation performance. Nonetheless, there are various reasons to consider that training is critical to effective innovation. Laursen and Foss (2003) argued that few studies had shielded the significance of the wide use of training to foster worker abilities and knowledge for innovation success. Training helps individuals absorb knowledge and innovation capabilities (Bauernschuster et al., 2009; Dostie, 2018). Thus, training fosters knowledge, expertise, and the ability of individuals to accomplish their duties, which will prompt firm innovation (Dostie, 2018). Mumford (2000) reports that firms might provide employees with comprehensive training to develop new knowledge, skills, and capabilities necessary to perform their innovative work behaviour. Investments in training can build employee know-how at all levels in the organisation, which is likely to provide an inexhaustible source of new ideas for further innovation (Macdonald et al., 2007). Bauernschuster et al. (2009) found that ongoing training ensures the opportunity for leading-edge knowledge, enhancing a firm’s tendency to innovate. However, the relationship between training and innovation has two critical drawbacks (Dostie, 2013; Easa & El Orra, 2020; González et al., 2016). First, studies have failed to decide between types of training. Studies have found that the amount of on-the-job training given by firms can be much higher than that of classroom training, consequently having a more significant effect on a firm’s capacity to innovate. Second, it is also vital to decide between types of innovation. However, Becheikh et al. (2006) reported that different types of innovation need different inputs.

Nevertheless, managers must focus on human capital development and embrace practices that cultivate knowledge and enhance workers’ abilities that evoke innovation. Michie and Sheehan (2003) found that training could help firms to facilitate product and process innovation. Laursen and Foss (2003) posit that training enables firms to greater process advancements and could augment product innovation. Training and development practices are not similar across all types of organisations. The organisational commitment and investment towards people vary significantly, and consequently, the findings from one setting cannot be generalised to another (De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010). Thus, the current study focuses on the effect of training and development practices on product, process and administrative innovation. Therefore, it can be hypothesised,

H4: Training and development practices positively impact product innovation.

H5: Training and development practices positively impact process innovation.

H6: Training and development practices positively impact administrative innovation.

Performance appraisal and Innovation

Performance appraisal encapsulates fostering risk-taking behaviour, demanding innovation, creating new tasks, peer evaluation, regular assessments, and reviewing innovation processes (Chen & Huang, 2009). Therefore, there is a relationship between individual innovativeness and firm performance (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005; Tan & Nasurdin, 2011). Performance appraisal elevates workers’ motivation to participate in the innovation process and facilitates the firm to attain anticipated innovation results (Curzi et al., 2019). Thus, it will outperform more prominent innovative activities (Tan & Nasurdin, 2011; Jiang et al., 2012). A study by Aryanto et al. (2015) found that strategic HRM practices, including performance appraisal, are positively related to the firm’s innovation. Firms can use performance appraisal to motivate individuals’ commitment and engage in creative thinking and innovation. Jaw and Liu (2003) stated that positive and constructive performance appraisal produces challenges, makes sense of accomplishments, and aids as a critical factor in evoking employee motivation. Performance appraisal can motivate individuals to commit to innovative abilities and stimulate firms to realise anticipated innovation results (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005). Tan and Nasurdin (2011) found that performance appraisal significantly predicts administrative innovation. Studies found a positive relationship between performance appraisal and product, process and administrative innovation (Chen & Huang, 2009; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Laursen & Foss, 2003). Drawing on a sample of 22 firms in the UK, Shipton et al. (2006) found a positive link between appraisal and firm product innovation. Various studies have found a positive association between performance appraisal and firm innovation in a developed country’s context (Chen & Huang, 2009; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Laursen & Foss, 2003); however, it cannot be generalisable in the developing country context. Therefore, it can be hypothesised,

H7: Performance appraisal positively impacts product innovation.

H8: Performance appraisal positively impacts process innovation.

H9: Performance appraisal positively impacts administrative innovation.

Compensation, Reward, and Innovation

Empirical results show that a compensation system significantly impacts employees’ innovative behaviour and elevates the firm’s innovation performance (Bysted & Jespersen, 2014; K. M. Sanders et al., 2010; Zhang & Begley, 2011). Because it can be a tool to foster such behaviour, it can also discourage other behaviours by only rewarding innovative behaviours (Chandler et al., 2000). Moreover, recognising individual and team accomplishments with compensation boosts innovation (Chen & Huang, 2009). However, few researchers have tracked a positive link between innovation and employee compensation (Balkin et al., 2000; Bos-Nehles & Veenendaal, 2019). Social exchange theory underpins the notion that compensation positively affects the innovative work behaviour of individuals because individuals who perceive their contributions are being honestly rewarded feel grateful to respond with discretionary additional role efforts such as innovative work behaviour (Janssen, 2000).

Further, the choice of innovation entails using incentive-based compensation. Ramamoorthy et al. (2005) found that individuals’ belief of compensations being presented could be directed toward a sense of responsibility to provide the firm with specific knowledge input and innovative ideas for the firm’s advancement. According to Bysted and Jespersen (2014), innovative firms must formulate captivating compensation strategies to entice the best competent individuals. Studies have found a positive link between innovation and compensation. Thus, firms must provide incentives to motivate individuals to develop creative and innovative activities (Zhang & Begley, 2011). However, individual performance-based compensation may enhance proactiveness and innovativeness by stimulating energy and spontaneous application for advancements (Lau & Ngo, 2004); this may simultaneously influence the creativity of individuals. Ironically, a controlling administrative style diminishes intrinsic motivation, reduces innovative performance and decreases adaptability, negatively influencing creativity and innovation (Beugelsdijk, 2008).

Extrinsic and intrinsic rewards motivate employees to take the exciting tasks, generate creative ideas, and develop successful new products and services (Mumford, 2000). The reward system urges individuals to get revived, increasing their support in contributing innovative ideas and prompting higher firm innovation (De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010). Employees are unwilling to perform innovatively owing to a lack of reward and incentive schemes (Waheed et al., 2019). Zoghi et al. (2010) found a positive link between incentive pay and product innovation. Jimenez-Jimenez and Sanz-Valle’s (2008) found that an organisation’s compensation system is positively significantly related to product, process and administrative innovation. However, studies are not available to make firm decisions on how compensation and reward systems impact different types of innovation. Moreover, compensation and reward practices differ across countries and organisations (De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010). Thus, it can be hypothesised,

H10: Compensation and reward systems positively impact product innovation.

H11: Compensation and reward systems positively impact process innovation.

H12: Compensation and reward systems positively impact administrative innovation.

Methodology

The study’s aim is well aligned with the survey research strategy that grants the large scale of data collection. The data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire embodies background information of the respondents, HRM practices and firm innovation. The study population consists of 3023 SMEs operating in the northern province of Sri Lanka. The minimum sample was designated based on (e.g., if (n=3000) the sample size is 341), the recommendation of (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). A simple random sampling technique was employed. Random Sampling is the most straightforward and general technique of choosing a sample, whereby the sample is selected unit by unit, with an equal probability of selection for each unit at each draw (S. Singh, 2003). The data of the study are the firm-level data from SMEs. It encompasses CEOs and managerial-level employees, especially those from the technical functions, such as engineering, process, product, quality, operations, production, and research and development (Ling & Nasurdin, 2010). A total of 300 questionnaires, and out of those distributed, 240 were returned, yielding a response rate of 89%. Of the returned questionnaires, 26 partly filled-in questionnaires were denied; ultimately, 214 were used in this study.

Measurement Instruments

This study adopts four sophisticated HRM practices, including recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, compensation and reward system, developing twenty-four-item scales. Recruitment and selection were measured using a five-item scale developed by Edgar and Geare (2005) were employed. The sample questions include ‘the recruitment and selection processes in this organisation are impartial’, and ‘favouritism is not evident in any recruitment decisions made here’. Training and development were measured by a five-team scale developed by Edgar and Geare (2005). The items include ‘my employer encourages me to extend my abilities’, ‘this organisation has provided me with training opportunities to extend my range of skills and abilities’. Performance appraisal was measured by a seven-item scale adopted from (K. Singh, 2004). The sample items include ‘performance of the employees is measured based on objective, quantifiable results’, ‘appraisal system in our organisation is growing and development-oriented’. The compensation and reward system was measured by a seven-item scale developed by (Balkin & Gomez‐Mejia, 1990) was employed. The sample questions include ‘the base salary is an integral part of the total compensation package’, the base salary is high relative to other forms of pay that an employee may receive in this organisation.

The three primary types of innovation: product innovation, process innovation, and administrative innovation, are used in this study (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008). Product innovation includes sample questions ‘number of new products/services introduced’, ‘pioneer disposition to introduce new products/services’. Process innovation includes sample items ‘number of changes in the process introduced’, and ‘pioneer disposition to introduce a new process’. Administrative innovation includes sample questions ‘novelty of the management systems’, search of new management systems by directives’. Except for demographic questions, A series of seven-point Likert scales (1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree) was utilised for each item.

Results

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to test the research hypotheses in this study. As a caveat, the measurement model’s reliability and validity were assessed before testing the hypothesis. This study assessed the construct’s internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951) and Composite Reliability (Raykov, 1997). The Cronbach’s alpha values for internal consistency fall between 0.70 and 0.95 (Hair et al., 2014). In this study, all seven constructs show a high level of internal consistency, exceeding a value of 0.7 (see Table 1). Another approach to evaluate internal consistency is composite reliability. According to Table 1, all the construct’s composite reliability is greater than .0.8, which is considered satisfactory.

The convergent validity was assessed using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), equivalent to the commonality of a construct. Table 1 depicts that the seven constructs’ AVE values are greater than 0.5, indicating the model’s convergent validity. Further, the discriminant validity was assessed using two classical methods: the Fornell and Larcker criterion. Referring to Table 2, applying the Fornell and Larcker criterion, when comparing the square root of each AVE on the diagonal (in bold) with the correlation’s coefficients (in italics) for each construct, the square root of each construct’s AVE is greater than the correlations with other constructs. Therefore, discriminant validity for this model is accepted. Second, the HTMT results showed (see Table 3) that all the values were significantly different from 1, indicating that all the values are under the threshold of .85 (Hair et al., 2014), establishing the discriminant validity of the reflective constructs.

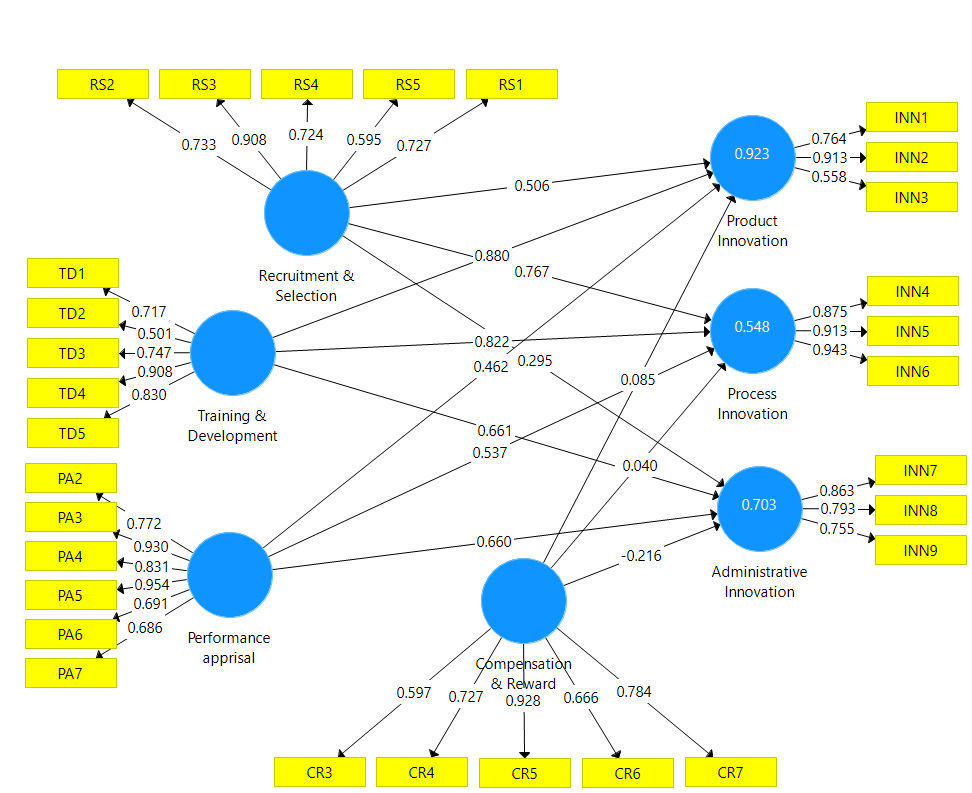

In Table 4, the R2 for product innovation was 0.923, process innovation was 0.548, and administrative innovation was 0.703. This indicates that 92.3% of the variance in product innovation, 54.8% in process innovation, and 70.3 % in administrative innovation are explained by the four latent constructs in the model, respectively.

Path models stand as illustrations to visually represent the hypothesis and the relationship of variables assessed when structural equation modelling is performed.

Table 4 shows that all the endogenous constructs Q2 values are greater than zero. Therefore, the path model’s predictive relevance was satisfactory (Henseler et al., 2009).

The hypotheses were tested with PLS-SEM using 5000 subsamples of bootstrapping, and the results are shown in Table 5. The hypothesis (H1) surmised that the recruitment and selection practices positively impact product innovation. The result showed that recruitment and selection practices positively impact product innovation (β=0.506, T=10.5862, p<0.000), and the value of f2 is 0.921 indicating a large-sized effect. Thus, H1 was strongly supported. The hypothesis (H2) foretold that recruitment and selection practices positively impact process innovation. The result proved that (β=0.767, T=9.3489, p<0.000) recruitment and selection practices positively impact process innovation. The f2 value is 0.360, showing a large-sized effect. Therefore, H2 was supported. The hypothesis (H3) stated that recruitment and selection practices positively impact administrative innovation. The path coefficients and their significant value (β=0.295, T=4.0046, p<0.001) indicate that recruitment and selection practices positively impact administrative innovation. The value of f2 is 0.080, indicating a small-medium-sized effect. Thus, supporting H3. The hypothesis (H4) stated that training and development practices positively impact product innovation. The result provides empirical support for training and development practices positively impact product innovation (β=0.880, T=20.1865, p<0.000), and the value of f2 is 2.566, showing a large-sized effect. Thus, confirming H4. The hypothesis (H5) predicted that training and development practices positively impact process innovation. The result endorsed that the training and development practices positively impact process innovation (β=0.822, T=11.8421, p<0.000), showing that H5 was supported. The value of f2 is 0.382, indicating a large-sized effect. The hypothesis (H6) proposed that training and development practices positively impact administrative innovation. The path coefficients and their significant values (β=0.661, T=10.9002, p<0.000) showed that training and development practices positively impact administrative innovation. The value of f2 is 0.375, showing a large-sized effect. Therefore, H6 was supported. The hypothesis (H7) stated that performance appraisal positively impacts product innovation. The result showed that performance appraisal positively impacts product innovation (β=0.462, T=12.1550, p<0.000), and the value of f2 is 0.764 showing a large-sized effect. Hence, H7 was supported. The hypothesis (H8) stated that performance appraisal positively impacts process innovation. The result demonstrates that the performance appraisal positively impacts process innovation (β=0.537, T=5.8100, p<0.000), and the value of f2 is 0.176 indicating a medium-large-sized effect. Therefore, confirming H8. The hypothesis (H9) surmised that performance appraisal positively impacts administrative innovation. The positive impact of performance appraisal on administrative innovation was statistically significant (β=0.660, T=8.8243, p<0.000). The value of f2 is 0.404, indicating a large-sized effect. Hence, H9 was supported. The hypothesis (H10) predicted that compensation and reward systems positively impact product innovation. The result showed that (β=0.085, T=2.0697, p<0.0390) compensation and reward systems positively impact product innovation. The value of f2 is 0.034, indicating a small-medium-sized effect. Therefore, H10 was supported. The hypothesis (H11) predicted that compensation and reward systems positively impact process innovation. The path coefficients between compensation, reward system and process innovation (β=0.040, T=0.3710, p<0.7108). Therefore, H11 was not supported. The value of f2 is 0.001, indicating a very small-sized effect. The hypothesis (H12) prophesied that compensation and reward systems positively impact administrative innovation. Evidently, (β=-0.216, T=2.4762, p<0.0136) compensation and reward systems negatively impact administrative innovation. Thus, H12 was also not supported. The value of f2 is 0.057, indicating a small-medium-sized effect.

Discussion

According to the study, the result of H1 confirmed that recruitment and selection practices significantly influence product innovation. These results parallel findings by other research studies (Laursen & Foss, 2014; Shipton et al., 2005; Tan & Nasurdin, 2011; Jiang et al., 2012) found that the well-aligned recruitment and selection practices of the calibre individual are the key players in evoking the conditions required for innovation performance. Unsurprisingly, innovative firms create systematic recruiting networks to absorb an ideal talent pool of creative and innovative individuals known to be the invaders in the innovation game (Jiang et al., 2012). Additionally, using various recruiting sources, ideal interview methods, and screening procedures will produce relevant information about every candidate before making a hiring decision (Jiang et al., 2012; Foss & Laursen, 2012; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Mumford, 2000). The result of H2 demonstrated that recruitment and selection practices significantly influence process innovation. This result is consistent with the previous research findings (Foss & Laursen, 2012; Lau & Ngo, 2004; Michie & Sheehan, 2003; Zhou et al., 2011). Further, the H3 result indicates that recruitment and selection practices significantly influence administrative innovation (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Mumford, 2000; Jiang et al., 2012). In line with recent studies, the ideal recruitment and selection practices enable SMEs to hire individuals with a range of skills and abilities, eliciting SMEs’ innovation because these individuals passionately showcase such behaviour and expertise across the different phases of the innovation process (Laursen & Foss, 2003).

In this study, the results of H4 give empirical support to training and development significantly influencing product innovation. This indicates that training aids in elevating individuals’ unique capabilities to generate new ideas that eventually produce new and better products and processes. The H5 statistics demonstrate that training and development practices are significantly influence process innovation was supported. Foss and Laursen (2012) posit that internal training is more conducive to process innovation, whereas external training might be conducive more to product innovation. Because external training allows individuals to build networks with more diverse knowledge. The H6 result proved that training and development significantly influence administrative innovation in SMEs. These findings are in line with the previous research findings (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Laursen & Foss, 2003; Shipton et al., 2005; Tan & Nasurdin, 2011; Weisberg, 2006), which claim that wide-ranging training and development practices leverage employees’ growth potential by acquiring critical competencies, skills, extending the breadth and depth of knowledge, and improving the ability to learn and apply learnt behaviour in the innovation process. Performance appraisal is a prime driver for shaping individuals’ behaviour competencies and inspiring them to achieve organisational goals (Laursen & Foss, 2014). In this study, the results of H7 proved that performance appraisal influences product innovation. The findings show that genuine performance appraisal strengthens employees’ performance and motivation, leading to innovation in SMEs. Furthermore, managers ought to consider that the appraisal system provides ongoing performance-based feedback and counselling because this enables employees to have faith in the performance appraisal system. The H8 provides empirical evidence that performance appraisal influences process innovation. The study emphasises that appraisal facilitates high-level learning in the workplace; thereby, the employee can absorb the confidence to capitalise on opportunities for innovativeness. Performance appraisal increases an individual’s intrinsic motivation and boosts them to be more creative.

Employee creativity/creative capital is the foundation for innovation (Ogunyomi & Bruning, 2016). Creative ability fosters new ideas or a different perspective of viewing problems, and feedback is a vital segment in performance appraisal, which facilitates employee creativity. Shipton et al. (2006) posit that during the appraisal period, feedback given to employees leads to understanding the voids between the expected and current, thus motivating them to be creative. Therefore, SMEs should capitalise on individuals’ creativity to realise innovation performance. The result of H9 evident that performance appraisal influences administrative innovation. These findings support previous findings that suggested that performance appraisal is positively associated with innovation in SMEs (Haneda & Ito, 2018; Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008; Ling & Nasurdin, 2010; Tan & Nasurdin, 2010). The study’s result indicates that the stronger the performance appraisal crafted by SMEs, the higher their product, process, and administrative innovation level. Paradoxically, Tan and Nasurdin (2010) found that performance appraisal influences administrative innovation, not product or process innovation. Compensation should reflect recognition, learning, quality of life, and psychological characteristics of work. Ability, motivation, and opportunity (AMO) theory recommends that compensation directly affects an individual’s attitude and is one of the motivation-enhancing HR practices (Lepak et al., 2006). Diaz-Fernandez et al. (2017) state that compensation practices are vital for innovation because they affect individual innovation behaviour. The result of H10 provides empirical support that SMEs having apt compensation and reward systems can facilitate product innovation. Drawing on equity theory (Adams, 1963) and social exchange theory (Blau, 1968), individuals estimate the reciprocate trade relationship with the firm based on their rewards. Individuals reciprocate the firm by exhibiting extra efforts on their jobs, more enthusiastically offering creative suggestions, and experimenting with new ways of doing things only when individuals believe that the firm values them using profit sharing and provides them with challenging, exciting, and essential work. SMEs should craft a compelling compensation strategy to attract and retain the best and most creative individuals in the quest for innovation. Previous findings show that compensation facilitates firm innovation through its ideal way of identifying individual and team attainments (Chen & Huang, 2009). The high intrinsic and extrinsic rewards enable individuals to strengthen their risk-taking ability at work, generate new ideas, and create new products and processes. Ironically, the finding of H11 showed that the compensation and reward system has no significant influence on product innovation. Notably, a growing debate in motivational psychology declares that extrinsic incentives, for example, monetary incentives, could be abortive as they tend to dispel the self-directed motivation vital for practical problem-solving, ongoing learning, creativity, and innovative performance (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The result of H12 revealed that the compensation and reward system significantly and negatively influences administrative innovation. A possible explanation for this is that, generally, SMEs do not have a proper compensation or reward system. That is, compensations are based on the manager’s subjective evaluations.

Further, the self-determination theory emphasises that rewards might reduce individuals’ motivation to showcase innovative work behaviour when their motivations are intrinsically inherent (K. Sanders et al., 2010). Moreover, inherently motivated individuals might believe rewards as coercion to perform work they at first did not pay attention to or curiosity, which may dampen their inherent interest in engaging in innovative work behaviour. Dorenbosch et al. (2005) and Sanders et al. (2010) have confirmed this adverse situation in organisations. Contrariwise, individuals who are not inherently motivated to engage in innovative work behaviour and think of it as an additional role are supposed to be rewarded for their extra efforts. The innovating SMEs requires a solid reward system to foster employee creativity. Because rewards can attract and retain creative individuals to the firms and offer motivation for the extra effort required to innovate. A reward system such as profit sharing might foster individuals’ creativity by integrating the profit to new ideas presented and utilised. Moreover, the reward system affects individuals’ drive to be creative, provide new ideas, ambitious to experiment are affected by the reward system. A distinct compensation system is needed when SMEs want to leverage innovation.

Practical implications

Significant practical implications are put forth for managers to obtain human resources skills and competencies, which would augment the firm’s innovation. The study chiefly reinforces managers’ understanding of the role of HRM practices, such as recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation and reward systems in increasing product, process, and administrative innovation. SMEs should create favourable HRM practices that foster the right atmosphere for their employees to enhance the sense of motivation and commitment in learning, creating and disseminating knowledge to create new products and processes.

The findings suggest that the recruitment and selection system should be rigorous, scientific, and impartial. When crafting recruitment and selection strategies, more attention should be given to the congruence between individuals and firm culture. Importantly, conveying a firm brand image to attract and retain future candidates is also vital; therefore, SMEs can consider employer branding as a strategy to recruit innovative individuals. Further, the selection system in firms should pay more attention to the candidate’s desired skills, knowledge and attitudes regardless of their characteristics. When hiring individuals, firms can deploy many different recruiting sources, and the hiring process should be comprehensive. Screening many applicants to fill job positions also aids firms in identifying creative individuals who can facilitate firm innovation. The study emphasises that policymakers need to make sufficient investments in human resources in SMEs. The government can compensate the investment in human capital interventions for motivating managers to provide employee training and development, which is in top priority. This study recommends that the training and development policy should include encouraging employees to extend the range of abilities, skills, and new knowledge in all aspects of quality, providing frequent opportunities for employees to discuss their training and development requirements with the employer, facilitating periodical on-the-job and off-the-job training for employees could incite innovative outcomes in SMEs. Notably, the study further suggests that the training needs should be realistic, practical, and based on the organisation’s business strategy; therefore, training needs should be identified through a formal performance appraisal system. Firms should focus on their employees’ external training and development opportunities to acquire exposure, new skills, and work-related knowledge relevant to the innovation process. This study proposes that SMEs focus on cross-functional training, job-relevant training, and innovative development methods, such as stress management, adventure training, leadership training, etc.

The findings attest that managers design growth and development-oriented performance appraisal systems, which can strengthen individuals to exhibit creative work behaviour and positive attitudes essential for innovation in SMEs. Assessing employee performance based on objective and quantifiable results is vital for firms because subjective criteria might make employees think that their appraisal systems are partial and based on individual preferences, which may have undesirable consequences.

Theoretical contributions

The study’s findings contribute to the theoretical development of the conceptual model for defining the association between HRM practices and firm innovation. Few studies assess these associations in the literature, and this dearth is very severe because of the growing importance of innovation. Second, this study contributes to the derivation of empirical support for predicting the model through data from actual cases in SMEs, even though explorations on the role of HRM in fostering innovation are missing in the HRM domain. Notwithstanding, during the past decade, research on the effect of HRM on firm innovation has been nascent in developing economics, and it necessitates further empirical understanding and elucidations (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2005; Laursen & Foss, 2003). This study contributes to the literature by empirically investigating the influence of HRM practices comprising recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal and compensation and reward systems, and firm innovation in Sri Lanka. The findings attest that HR practices such as recruitment and selection, training and development, and performance appraisal positively influence firm innovation. However, compensation and reward systems positively influence product innovation, not process and administrative innovation. A common personnel management philosophy is ‘hire for attitude and train for skill’ (Chang et al., 2011); the study argues that to augment SME innovation, a good strategy can be “hire for attitude and train for skill.”

Laursen and Foss (2003) claim that systems or complementarities of HRM practices are significant to innovation performance, but the contribution of individual practices is insignificant. Arguably, this study confirmed that individual HRM practices are significant determinants of firm innovation in developing economics. It is not defensible to say that the HRM system is more important to innovation than individual practices. Debatably, studies on SMEs are comparatively inadequate compared to the other sectors in Sri Lanka. Exclusively, this study has paid more attention to Sri Lankan SMEs. The study’s findings fill the void in the literature that lacks empirically examining the relationship between HRM practices and firm innovation in SMEs. Additionally, the contribution of this study is significant because it is being conducted in a different cultural context compared to the existing literature based on studies conducted in different cultural contexts.

Conclusion

Based on the theoretical ground and methodological rigour, the underlying purpose of the research was to investigate whether HRM practices (e.g., recruitment and selection, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation and reward systems) influence firm innovation (e.g., product innovation, process innovation, and administrative innovation) in Sri Lankan SMEs. It was intriguing to witness that not all HRM practices contributed to the firm’s innovation performance over the time studied individually. The findings showed that recruitment and selection, training and development, and performance appraisal positively influence firm innovation in SMEs. Notably, the result showed that compensation and reward systems positively influence product innovation, not process and administrative innovation. Moreover, the influence of compensation and reward systems on process innovation was found to be insignificant, and it was found that there was a significant negative influence of compensation and reward systems on administrative innovation. These findings conflict with other research findings that claim compensation and reward systems are the most robust devices for producing innovation. Drawing on AMO (ability, motivation, and opportunity), the findings of individual HRM practices appear to confirm that ability-enhancing practices (comprehensive recruitment, rigorous selection, and extensive training and development) and motivation-enhancing practices (performance appraisal, robust compensation, incentives, and rewards) are the most important for leveraging innovation. Therefore, the findings indicate that firms presenting a sophisticated HRM approach tend to be significantly more innovative in product, process, and administrative innovation. Thus, SME owners/managers should craft an exhaustive HRM practice to foster employee capabilities and motivate them to innovate.

Limitations and future research directions

This study is not without limitations. One of the significant limitations of this study, it relies upon a cross-sectional research design. Although the findings are consistent with the theoretical reasoning, the cross-sectional design might not exclude causality regarding the hypothesised relationships. In this study, all the measures were self-reported data marshalled at a single moment in time through a single respondent that may have the likelihood of common method variance. As such, future researchers could focus on this using longitudinal research design with innovation observed at a minimum year or longer after assessing the HRM practices of a firm.

Similarly, another limitation is that the selection of HRM practices is somewhat limited and specific. Even though the chosen HR practices that best relevant to the Sri Lankan SME sector, it might be worthwhile to consider other HR practices. For example, teamwork (Shipton et al., 2006), career paths (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2008), information sharing (Bos-Nehles & Veenendaal, 2019), exploratory learning focus (Shipton et al., 2006), job security, participation, promotion, variable reward (De Saá-Pérez & Díaz-Díaz, 2010), leadership, employee diversity (Haneda & Ito, 2018). This study did not consider for interaction effects between the various HR practices and firm innovation. For example, Shipton et al. (2006) proved that the impact of appraisal, training, induction, and contingent reward on product and process innovation is moderated by exploratory learning. It is also valuable to investigate the association between HR practices and firm innovation by incorporating mediating and moderating variables such as creativity (Jiang et al., 2012), knowledge management (Chen & Huang, 2009), and human capital (Nieves & Quintana, 2018). Besides, this study investigates Sri Lankan SMEs, potential cultural limitations might exist, and future research can focus on the empirical investigation in different cultural contexts to generalise the study variables.